Contents

Contents

For David Birt

By the same author

The Desired Effect

Boris: The Rise of Boris Johnson

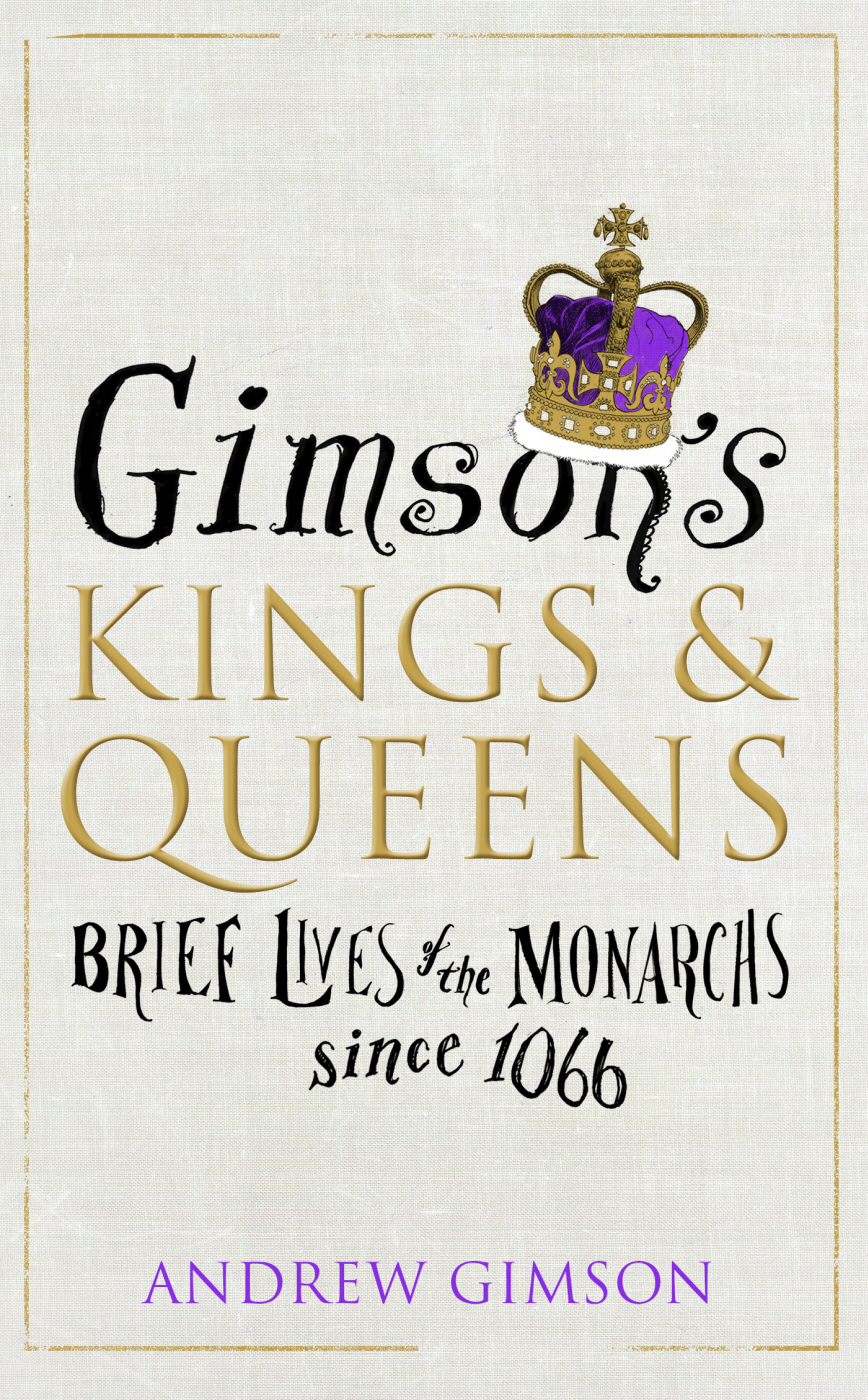

About the Book

A few faults are indispensable to a really popular monarch George Bernard Shaw

Gimsons Kings and Queens whirls us through the lives of our monarchs from 1066 and William the Conqueror right up to Queen Elizabeth II and the present-day to tell a tale of bastardy, courage, conquest, brutality, vanity, vulgarity, corruption, anarchy, absenteeism, piety, nobility, divorce, execution, civil war, madness, magnificence, profligacy, frugality, philately, abdication, dutifulness, family breakdown and family recovery.

Written in Andrew Gimsons inimitable style, and illustrated by Martin Rowson, Gimsons Kings and Queens is both a primer and a refresher for anyone who can't quite remember which were the good and bad Edwards or Henrys, or why so-and-so succeeded to the throne rather than his second cousin.

Published in August 2015, to coincide with the moment (in September) when Elizabeth II will (barring accident or shock abdication) become the longest-serving English monarch ever, Gimsons Kings and Queens will be the most entertaining and instructive book on the English monarchy you will ever read.

About the Author

Andrew Gimson is the author of Boris: The Rise of Boris Johnson, published by Simon & Schuster in 2006 and described as brilliant, scintillating and an effervescent delight. He writes for a wide range of newspapers and magazines, and is a contributing editor to ConservativeHome.com. He lives in London.

INTRODUCTION

This slim volume contains brief lives of our last forty kings and queens, from 1066 to the present day. They met with triumph and disaster, but were very seldom boring, for they played a role which exercises an irresistible hold on the imagination. As J. H. Plumb remarks in The First Four Georges, It is almost impossible for a monarch to be dull, no matter how stupid.

The book was prompted by the realisation that on 9 September 2015 Elizabeth II would become our longest-serving sovereign, surpassing Queen Victorias record of sixty-three years and 216 days on the throne. Amid the celebrations of that landmark, many might also wonder, without necessarily voicing the thought, how it is that the English and then British monarchy has survived for so long. For the present Elizabeth, and her heirs Charles, William and George, recall in their very names their forebears.

The story opens with an illegal immigrant, William the Conqueror, who never learned his new subjects language, though he well understood how to compel their obedience and seize their lands. It continues with such extravagant figures as Richard the Lionheart, the greatest knight in Christendom, and Richard III, regarded by some as the greatest criminal. We see Henry VIII degenerate from a Renaissance prince into a tyrant, casting off wives and servants with merciless finality but making England independent of Rome. His daughter, Elizabeth I, upholds that independence by the heroic expedient of steering a middle course where none seemed to exist.

Charles I would not admit the need to find a middle course, so lost his head. William III, the Dutchman who became our most underestimated monarch, played a vital but forgotten role in the assertion of English liberty. Victoria turned the monarchy into the symbol of a new morality, and a new empire. Her great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II, survived the loss of that empire by practising Christian virtues which have become unfashionable.

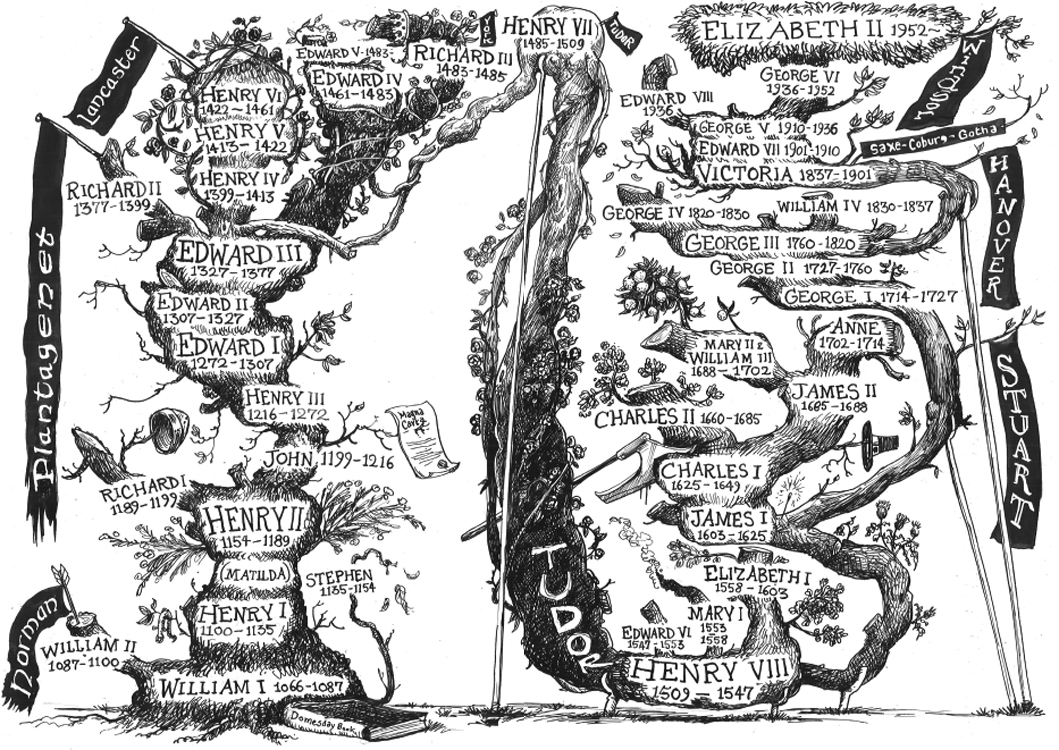

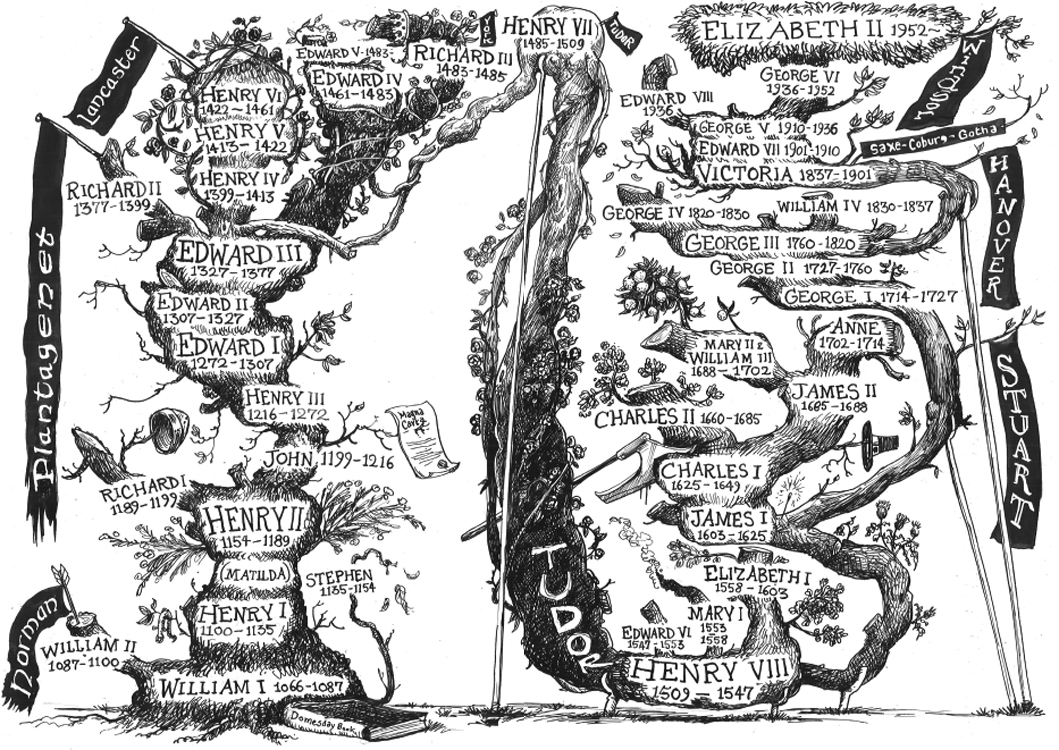

Because the monarchy is seen as a source of stability, it is easy to fall into the error of imagining that its history must be stable. We glance at its family tree and find ourselves lost in admiration of the millennium of continuity which is there declared.

But look more closely, and one finds the story is marked by savage discontinuities: by family quarrels settled in battle or by murder and usurpation. These pages tell a tale of bastardy, courage, conquest, brutality, vanity, vulgarity, corruption, anarchy, absenteeism, piety, nobility, divorce, expropriation, execution, civil war, madness, magnificence, profligacy, frugality, philately, abdication, dutifulness, family breakdown and family revival.

The first aim of this volume is to entertain, not to instruct. It is not a textbook, and should not be used as an aid to passing exams, for its attitudes might annoy the examiners, and will distress professional historians who attach exaggerated importance to their own discoveries. Brevity has trumped comprehensiveness: the book cannot offer an adequate account of what was happening in Scotland, Wales and Ireland, or in many other fields of English life.

Between the ages of eight and thirteen, I was lucky to have a history master, David Birt, who taught his pupils the things it was a pleasure to know, and not just the things one ought to know. His favourite king was John (11991216), conventionally regarded as the worst in English history.

Thanks to his early teaching, I acquired some slight grasp of the whole sweep of English and British history, which I have ever since felt to be slipping from my not very retentive memory, so that gaps opened up where I had no idea what was going on. Although I read history at university, I found myself responding to any question about the past with the apologetic claim that it was not my period. I no longer knew when the Plantagenets began, or indeed when they ended. The present volume might be described as a refresher course for those who used to know some history, and an introduction for those who never did.

There are many admirable biographies of individual monarchs. But I do not know of a recent, readable volume which covers them all in under 250 pages. The exception to this rule is 1066 and All That, which by redefining history as what you can remember comes in at a more manageable 116 pages. But the running joke in that classic, namely that everything is misremembered, is not quite so funny now that most of us were never made to learn these things in the first place.

A Shortened History of England, by G. M. Trevelyan, published in 1942, is a masterpiece of Whig eloquence, the best of its kind ever written, but although an abridgement, it still stretches to 560 pages. The English and Their History, by Robert Tombs, published in 2014, offers a penetrating narrative informed by wide scholarship, but is 890 pages long. The great difficulty is to know what to leave out. But there is also a kind of liberation in deciding not to try to say everything.

I have called this volume Gimsons Kings & Queens a vainglorious title in order to emphasise that it offers a personal view. At the end of the book, I offer a few thoughts about why the British monarchy has lasted so long.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My greatest debt is to David Birt, who taught me history at Abberley Hall School, and over the past year has placed a lifetimes knowledge at my disposal. This book is dedicated to him. I am indebted too to Basil Morgan, the always encouraging and amusing head of history at Uppingham School; and to my supervisors when I read history at Trinity College, Cambridge, including Walter Ullmann, Brian Wormald, Jonathan Riley-Smith, Shirley Letwin and Norman Stone. Thomas Kielinger, author of a fine biography of Queen Elizabeth II in German, allowed me the run of his royal library. James Knox lent