Foreword

At the end of World War II, the Nuremberg war tribunal sentenced the Waffen SS, possibly the finest fighting force the world has seen since Leonidas and his Spartans at Thermopylae, the bravest of the brave, collectively as war criminals. As an ex-Waffen SS volunteer, well aware of the strong discipline and high morale of these exceptional warriors, originally all volunteers, I decided to write down the experiences of some Swedish SS comrades in the fight against the Red Army.

My first interviewee was Erik (Jerka) Wallin from Stockholm. In late 1945 he had just been released from a Swedish prison where he had served a few months for the 'theft' of his Swedish army uniform. Before crossing the border to join the Waffen SS he had wrapped it in a neat parcel, which somehow had gone astray. During the war it was no crime in Sweden to join the German or Finnish forces against the Soviet Union. After the war, however, the Swedish authorities felt embarrassed about their past neutrality and became anxious to establish good terms with Sweden's large neighbour in the east. So Jerka' had to go to jail as an expression of Sweden's new-found friendliness with the Soviet Union.

Erik's neighbours in prison were hard-boiled violent repeat criminals. Being 'politically correct' criminals, it was hard for them to tolerate this disgusting war criminal in their cosy Swedish prison, equipped with all modern conveniences. Erik had been quite a good amateur boxer, but he hadn't a chance when they made it a habit to collectively beat him up, with the wardens as onlookers.

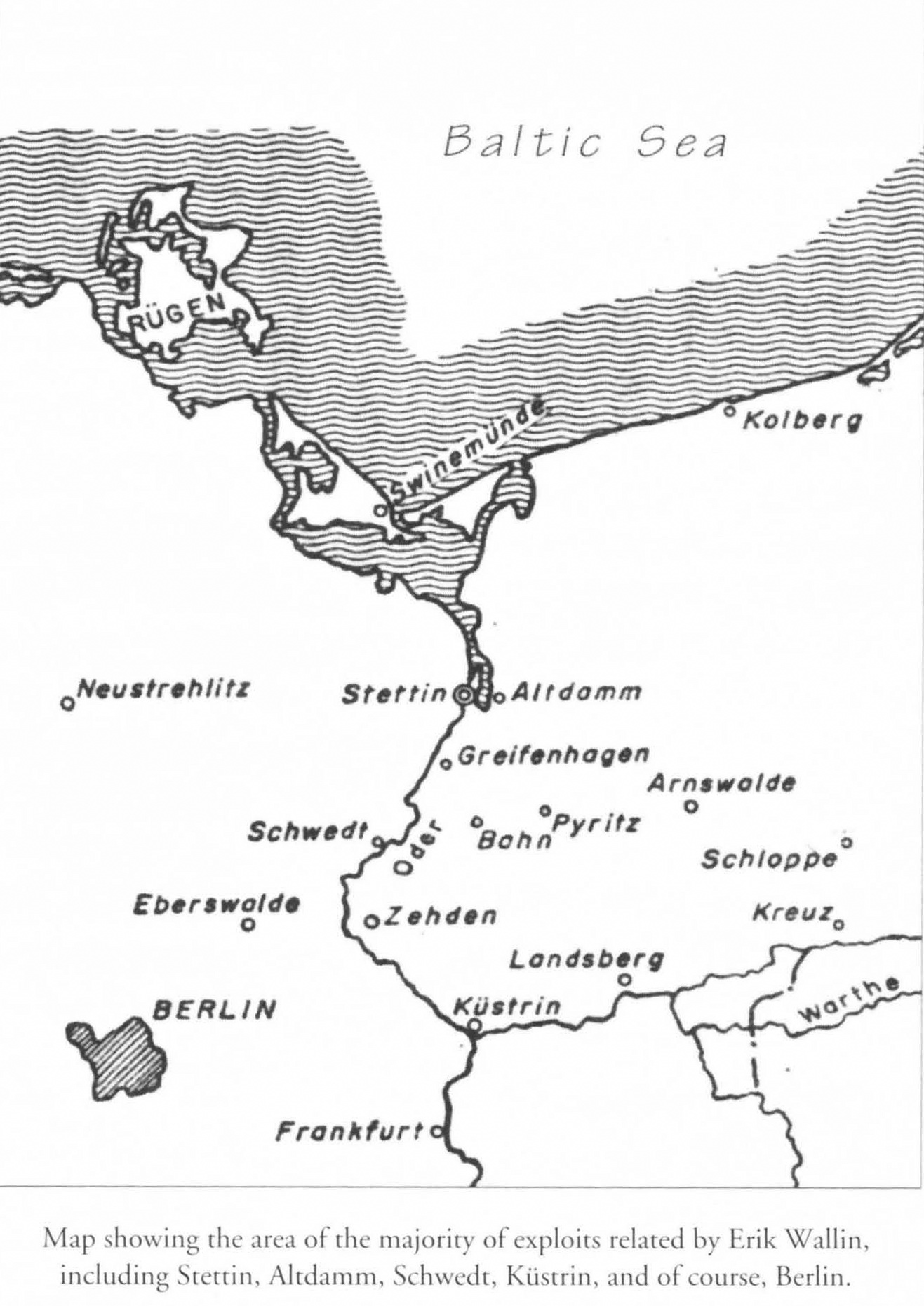

He had been through the war up to the fall of Berlin, with a very short stint as a Red Army POW. It turned out that his experiences gave enough material for this book, so I forgot about further interviews. He visited me every evening, and between cups of coffee and cigarettes he talked `til late in the night, while I took down the details. Jerka's tale is not a continuous chronological description of his participation in the last six months of the Second World War, rather some episodes in the tremendous battles fought during those days.

As a marked man - after the war Sweden was no longer neutral - I was jobless, so in daytime I typed what he had told me the night before. I was in a bit of a hurry, because the profit from the sale of the book was to cover the debts of our weekly paper Den Svenske, the finances of which were in terrible shape. In two weeks the job was finished. We printed only one edition, which was sold out within a few weeks. It did not occur to us to print a second edition, because the first one had already solved our financial problems. In 1947 a German translation was published in Argentina where thousands of SS men - Dutch, French, Belgian, Scandinavian, and of course German - had sought refuge. In the mid 1990's after 50 years! - pirate editions started appearing in Scandinavia and Germany. So, some of the book contents may be worth reading ...

Erik Wallin continued his eventful life in various countries - like many comrades, he became restless - some rather exotic, such as Morocco and Afghanistan. He met many interesting people and even became friendly with the last (or latest?) King of Afghanistan, Zahir Shah, who has lately enjoyed some publicity with his return to Kabul. Zahir Shah liked to listen to Jerka's war escapades. Among other notables Erik met was Ilya' Ehrenburg, Stalins court jester, one of the few intimates of the Red Tsar to survive Stalin's 'clear-outs'. Ilya and Jerka must have had some interesting things to tell each other ... In later years, Erik and I used to meet in Stockholm for a few days once a year, reminiscing over bratwurst, sauerkraut, Kommisbrot and beer. By then I had lived in Argentina for almost fifty years, a very, very different country. Erik's 'light' went out one evening at a get-together of Division Nordland veterans in Germany. It happened fast, as so many things in his life did!

Thorolf Nilsson Hillblad

Coeur d' Alene, Idaho, 2002

Unsere Ehre heisst Treue

"Our honour is our unbreakable loyalty"

(motto of the Waffen-SS)

New Year's Eve, 1944-1945

Together with Army Group North, which consisted of the 16th and 18th armies,III.(Germanic) Panzerkorps under SS-Obergruppenfhrer Felix Steiner was cutoff the other German forces, in Courland. The seaport of Libau was of vital importance for the encircled forces. From the middle of October 1944 Steiner's Panzerkorps, which consisted of the 11th SS Panzergrenadier Division Nordland, and the 23rd SS Panzergrenadier Division 'Nederland; held the front at Preekuln Purmsati Skuodas.

The main line of defence ran along the railway, through the ruins of Purmsati and the village of Bunkas. On one side of the railway tracks lay the SS soldiers, and on the other, the Red Army. About 1 kilometre north of Purmsati lay the village of Bunkas. At times it was very cold temperatures below 30C were recorded.

We sat round the roughly-made bunker table playing cards, and listening to the front's New Year radio appeals from the highest commanders of the different services. We could also tune in to Christmas music. The bunker had been decorated, as well as we could, on Christmas Eve. There was a Christmas tree, fresh spruce-twigs, tinsel, and small items we had received in the recent field-post parcels. By New Year's Eve it was still looking as homely as it could in a temporary underground bunker. Soldiers' rough, chapped and frozen hands had tenderly and carefully conjured up this Christmas treasure for all to share. We still cared for such in the days between Christmas and New Year.

On the stove were some canteens with steaming Glogg, our Nordic version of English mulled and spiced wine. Every now and then each man took a mouthful from one of the canteens, for once carefully cleaned. We had enjoyed smoking lots of the generously distributed Christmas cigarettes, from field-post parcels that had also contained sweets and biscuits. The playing cards regularly slammed down on the rough table. Quiet humming to the melodies on the radio was only occasionally interrupted by some racy comment on the game, or by a violent snore from one of the comrades of the relief guard sleeping on the floor, the exhausted sleep of a frontline soldier.

There was a jarring signal from the field-telephone. It was the company commander. He wanted to speak to me about a planned fire correction for the next day. Our mortar fire was to be aimed at a new target in the enemy positions. He ordered me to go to our outpost closest to the enemy, outside the village, to try to get a general view of the area that my mortars would fire on in the morning.

One of my comrades took over my cards. I put on the snow camouflage overall, took the ammo-pouch for the submachine-gun and put the white-painted steel helmet on my head. On the way out, I took a generous swig of Glogg from my canteen on the stove as I looked around the bunker. Suddenly, it seemed so warm, cozy and full of comfort, even with its stamped-down earth floor. On the partially-boarded, black-brown, damp walls fluttered the shadows of the men around the radio, in the light of the Christmas candles. With my trusty MP40 submachine-gun under my arm, I nodded to the men at the table, shoved the white-frosted door open with my foot, and went out into the night.

Next page