Copyright 2018 by Christopher C. King

An earlier section of appeared in the Oxford American Magazine .

An essay that became a section of appeared in the Paris Review Daily .

Translation of Anathema Se Xenitia, Samantaka, and traditional mirologi courtesy of Demetris P. Dallas. Translation of Panegyri of Kastritsa courtesy of Jim Potts. Translation of The Bridge of Arta courtesy of Thomas Scotes.

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Beth Steidle

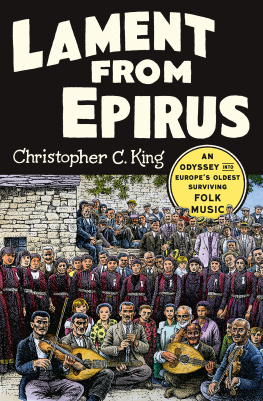

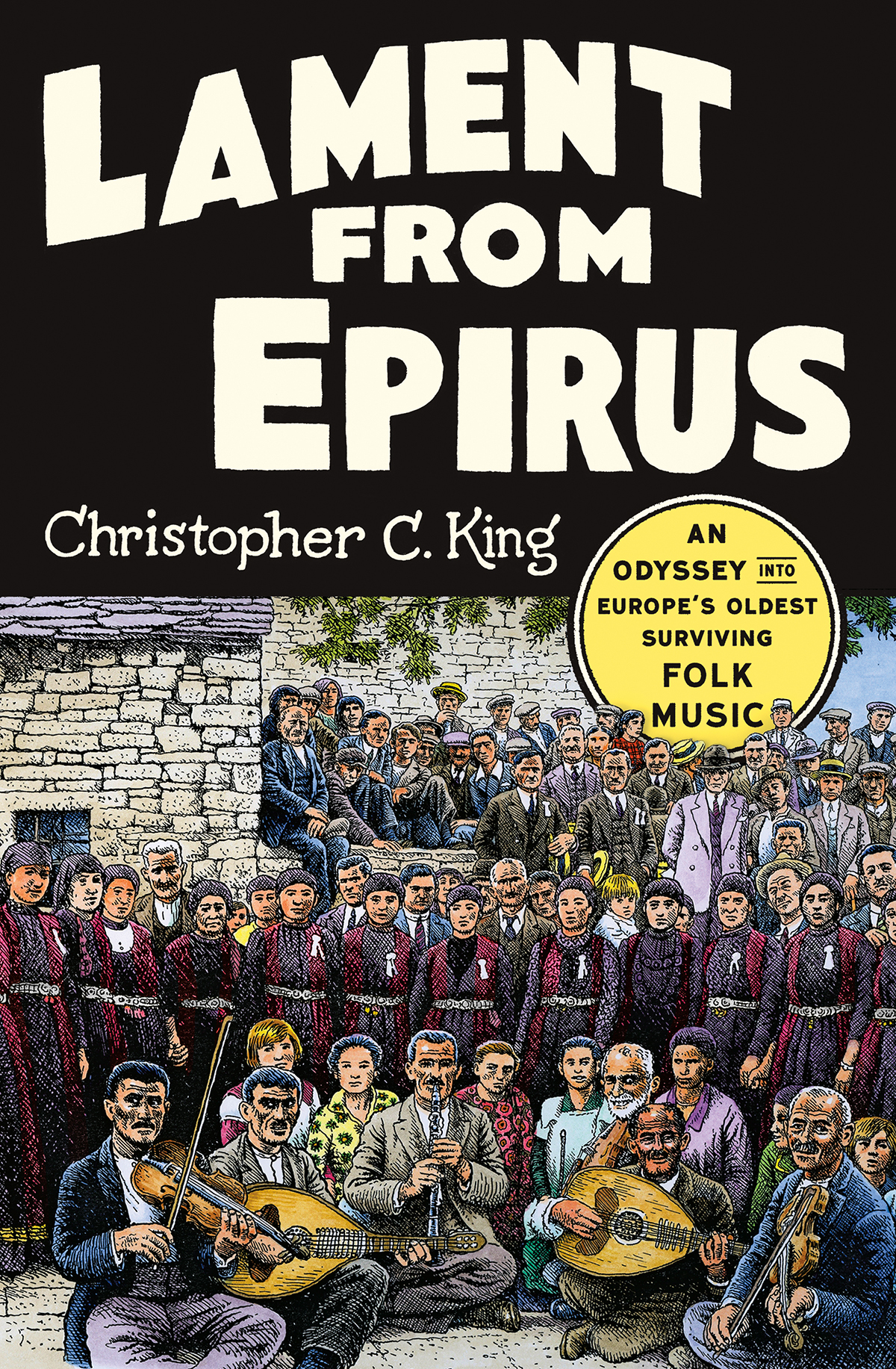

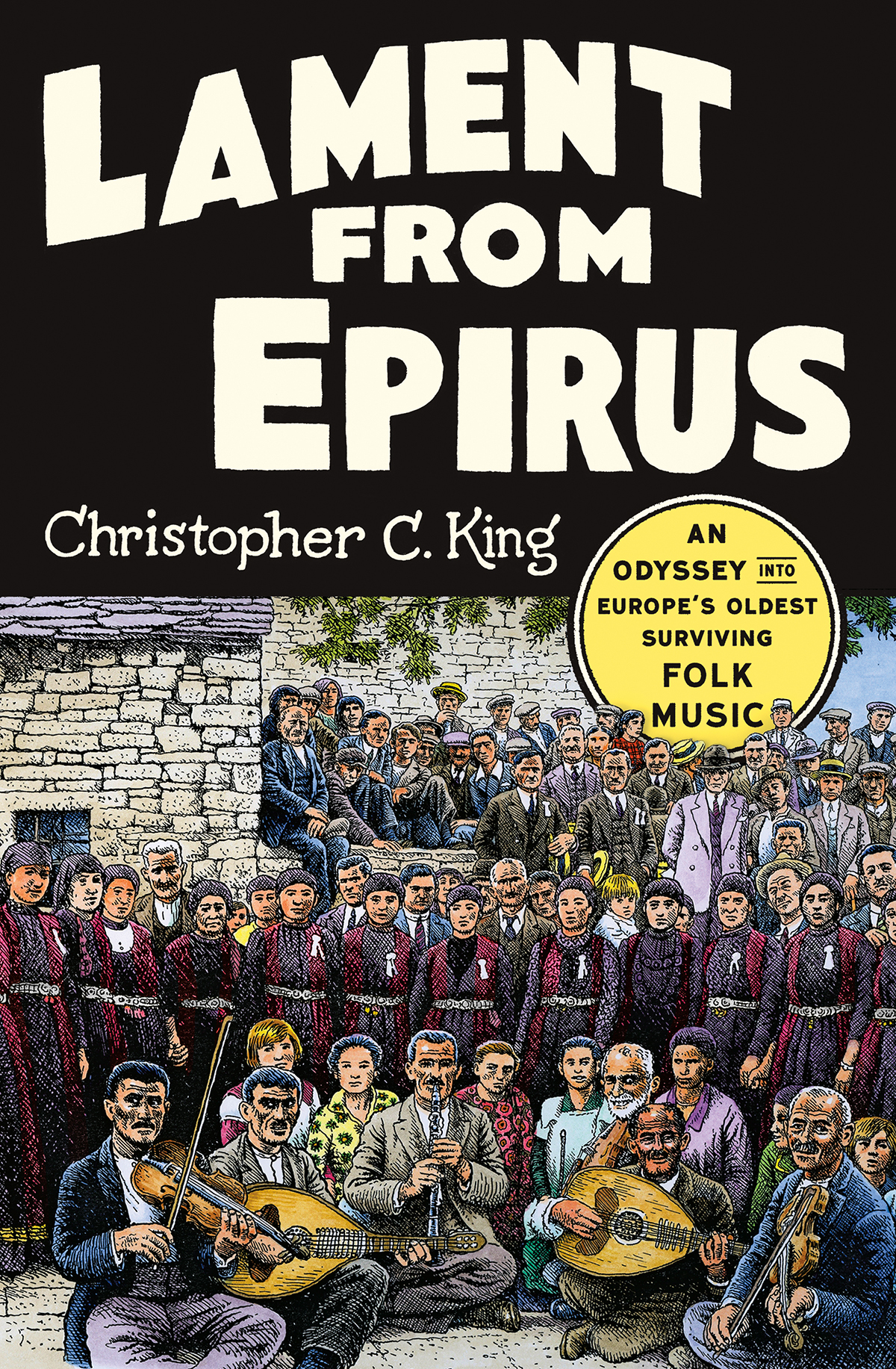

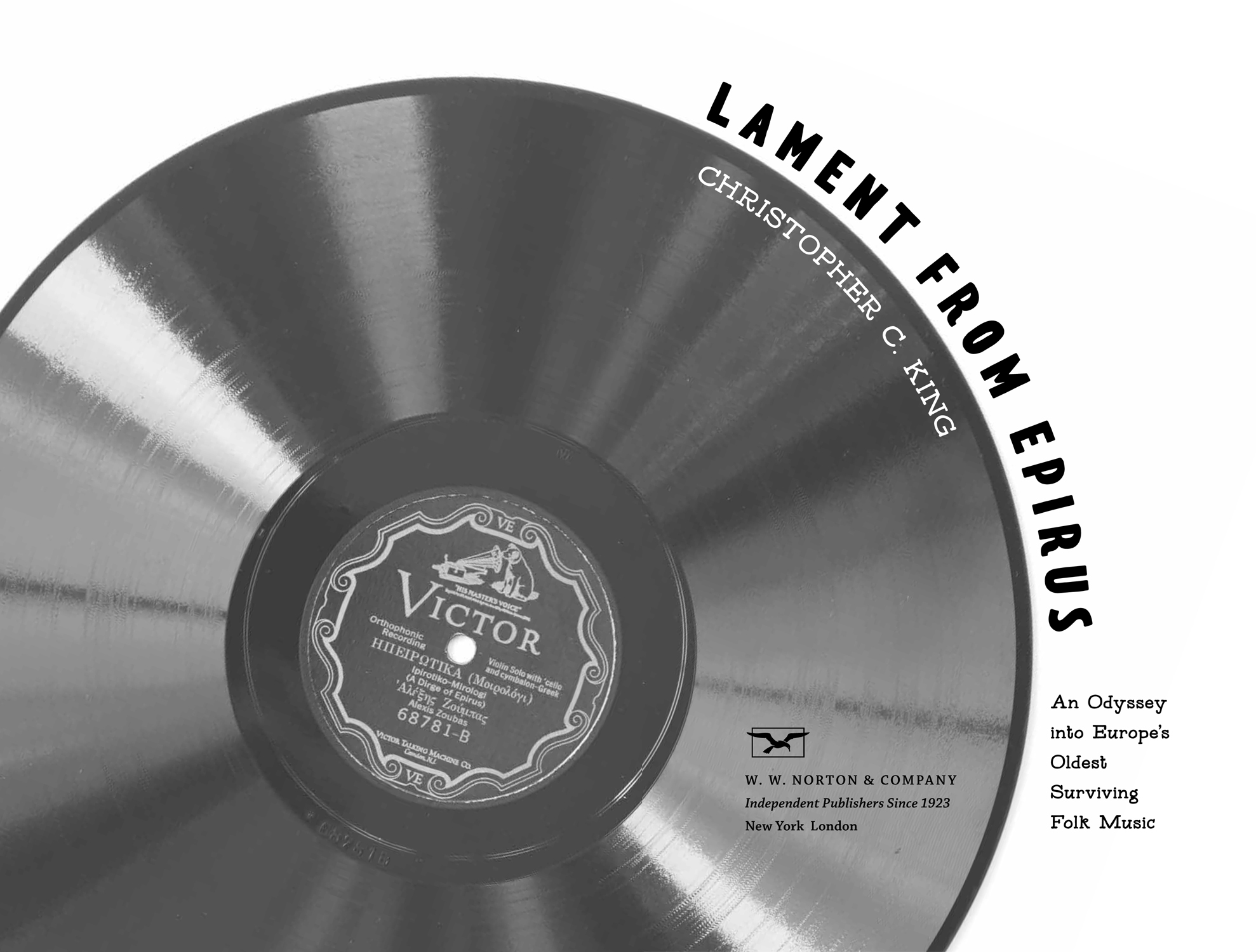

Jacket illustration: Lazaros Rountas Epirotic Orchestra in Vista, Zagori circa 1930 / R. Crumb

Jacket typography R. Crumb Jacket design: R. Crumb and Mark Melnick

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: King, Christopher C., author.

Title: Lament from Epirus : an odyssey into Europes oldest surviving folk music / Christopher C. King.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018001031 | ISBN 9780393248999 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Folk musicEpirus (Greece and Albania)History and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3604.7.E65 K56 2018 | DDC 781.62/804953dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018001031

ISBN 978-0-393-24900-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Charmagne

Listening to the phonograph record is like eating with false teeth.

KAMIL AL-KHULAI, 1904

CONTENTS

LAMENT FROM EPIRUS

A TIME-TRAVELER, A PERSON FROM THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY , stands on a cliff overlooking a mountain pass in southern Europe, in northwestern Greece, a few thousand years after the end of the last Ice Age, having traveled back in time by way of some technology unknown to us. This traveler is observing human beings while they interact with one another in this challenging, remote environment.

Something is happening among these proto-Europeans. One person places a long wooden shaft, holes bored along the side, to his lips, producing sound. Other sounds exit the mouths of the surrounding people. The collective sound appears fragmented to the listenerthe time-travelerstanding above. At times the voices and the flute notes appear smooth, mellifluous, but then disjointed and abrupt. During this flood of sound, members of this group move in cryptic yet intentional ways. When this lush cacophony ceases, so too do the movements of the people.

What is going on down there?

Any of us could be this time-traveler. And any of us would realizebased on our observationsthat these people are communicating. We perceive sound and movement, assuming cause and effect. The question that should linger in our minds is this: are we observing a use of language, a use of music, or something elsean alien and impenetrable behavior?

There was a time in our distant human past when we were cold, hungry, and fraught with anxiety. In order to live we had to communicate with one another. Language is a very powerful tool to exchange meaning. It is necessary for cooperation within a species; it is a tool for survival. Music, too, is a potent means of exchange. But have we ever considered musiclong thought of as a form of entertainment or of symbolic expressiona tool for survival?

Music is as universal and as primal as language. There is evidence of musicality from every cultureboth preliterate and literateknown throughout the world.

Music permeates our lives: listening to it, making it, judging it, or collecting it. Practically every daysometimes several times a daywe hum a melody or repeat a line from a song that has unconsciously become embedded within us.

Language itself is intertwined with music. We often describe the sonorous qualities of the human voice and of nature with musical terms such as melodious or rhythmic. The tonal properties of instruments are likened to the sounds of humans: The violin pierced the air like a womans voice or The trumpet wailed as the drums growled. Likewise, it would be impossible to describe music without the lexicon of human emotion sad, happy, unhinged .

Our earliest form of communication may have been a blending of the melodic with the spoken, much like a birdsong. Few would argue that birds communicate nothing with their patterns of tones. And most would agree that avian utterances are arrangements of sound with an aesthetic dimension: they are musical.

Our early ancestors may not have recognized a binary, the verbal and the musical. As humans evolved, perhaps linguistic expression and melodic expression bifurcated. Like a vestigial part of our anatomy, music may have mutated or atrophied, obscuring its original purpose.

Toddlers, before they form words and sentences, often communicate with a mixture of the verbal and the musical. My daughter Rileybefore she uttered her first sentence, Angels eat babies eyesexpressed herself with piercing melodic lines that sounded like the cries of a pterodactyl sweeping across the sky. My wife and I inferred from these sounds that she wanted to be fed. This was the language-song of a hungry child.

Epic poetryamong the earliest artifacts of our propensity for storytellingwas musical. Many have theorized that repeated phrases and tonal patterns helped the ancient poet-singer recall the versesan early mnemonic technique. Listeners were pleased to hear melodic refrains punctuated with action and meaning. When these rhapsodic songs were captured in writing by pressing a stylus into a substrate, we preserved the words along with trace elements of their musicality.

But evidence of musics origin is fragmented. Humanity is a careless time-traveler. We rarely mark our passage through the millennia in a conscious way . Evidence has been lost, leaving an incomplete trail of artifactsof cluesabout the origin of this universal human activity, music making. Often we are left wondering what music actually is.

John Blacking proposed that music is humanly organized sound, a pat yet inclusive definition. Blacking was a pioneering ethnomusicologist who contrasted the folk music of central and southern Africa with the classical music of Europe. In his book How Musical Is Man? Blacking advanced the notion that listeners are just as musical as performers in traditional folk economies. In cultures that do not write down their music but rather transmit their songs and dances from one generation to the next, the ability to critically listen to and appraise a traditional folk performance is as important and as much a measure of musical ability as is performance, because it is the only means of ensuring continuity of the musical tradition.

In Blackings view much of Europe and the Wests classical or art music is preserved differently: it is written in standard musical notation. A proportionally small number of people know how to read music. Those who assess a given performance in the Westfor instance, an opera criticbelong to an exclusive clique. Therefore Western culture sees musicality limited to those who are trained to perform or who are educated in aesthetic criticism or music theory.

Next page