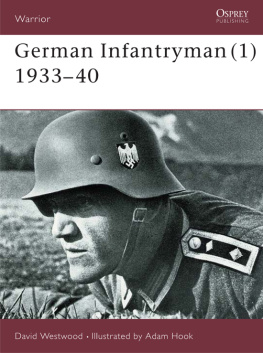

| Warrior 59 |  |

German Infantryman (1) 193340

David Westwood Illustrated by Adam Hook

CONTENTS

GERMAN INFANTRYMAN (1) 193340

INTRODUCTION GERMANY 191933

The aftermath of the First World War

When the dust and arguments settled after the First World War, the victorious Allies imposed a series of restrictions on Germany in the Treaty of Versailles (June 1919). Among other things, the treaty stated that by 31 March 1920, the German army was to consist of no more than 100,000 men, of whom 4,000 were to be officers. The treaty conditions also specified the structure and organisation of this army: there were to be 21 three-battalion infantry regiments (with 21 training battalions attached), and each regiment was to have one mortar company. There were to be proportionally larger numbers of cavalry, plus seven artillery regiments of three battalions, and seven field engineer, signals, motorised and medical battalions, a total of seven divisions in all.

The German army of 34,000 officers and nearly eight million men which had fought from 191418 was to be reduced to insignificance, with no hope of operations larger than at corps level, and most importantly from the point of view of the French, no prospect of cross-border excursions. Furthermore, the Germans were to be prevented from forming reserves, by virtue of the restriction that men had to serve a minimum of 12 years, and officers 25 years before discharge.

The political turmoil of this period was keenly felt throughout Europe, and the heartfelt relief at the end of the slaughter was universal. Germany had removed its emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, at the end of the war and was struggling to find a form of government that had the power and prestige to set Germany on the way to recovery. Germany was economically and militarily bankrupt. Although American efforts to shore up what was a much weakened nation helped to some extent, political unrest was to continue in Germany until the start of the Second World War, despite the arrival of Adolf Hitler on the world stage in the 1930s.

Germany was bordered by France to the west with an army of one million. To the east was Poland, traditionally regarded as a threat by German minds, especially with its superior force of 30 infantry divisions and ten cavalry brigades. Geographically the Danzig corridor in the east separated East Prussia from the homeland, and in the Rhineland in the west, the Allies had insisted upon permanent demilitarisation as well as occupation for 15 years. To add to this and other burdens there was also the matter of reparations, a matter upon which the French were vehemently insistent.

General von Seeckt

General Hans von Seeckt became de facto Commander-in-Chief of the German army on 2 April 1920, and was faced with transforming it into the 100,000-man Reichsheer as specified by the Versailles treaty. He served until 7 October 1926, and, despite a personal preference for cavalry, he conceived and promulgated a doctrine which was to form the basis of German operational military thought and deed until the end of the Second World War.

Von Seeckt served on various staffs during the Great War, ending up as Chief of Staff of III Corps. For five months in 1919 he was Chief of the General Staff and spent much time immediately after the war evaluating operational concepts in which the machine gun, barbed wire, artillery and the tank had dominated. He realised that the Imperial Army was a spent force which could not fight any future war as it had done the last.

No matter what von Seeckts political views were, his actions would affect the military world fundamentally. To avoid the tremendous losses incurred by the return to medieval siege tactics of 191418, he realised that military strategy had to be based on mobility. No doubt, like Field Marshal Haig, he had longed to loose the cavalry into the enemys rear after a breakthrough of the front-line enemy trenches. More perceptively, he also saw that such breakthroughs were not easily achieved once the enemy had time to dig in and fortify. He had, however, noted the successes of the Sturmgruppen who had made such progress in 1918. What he emphasised was that such breakthroughs had to be supplied, and then resupplied with men, weapons, food and all the other prerequisites of warfare.

The size of the new army was always a consideration, but his plan was that the army would enlarge itself as soon as it could. The political situation was not suitable until 1933. The essence of his teaching was that tactics depend upon co-operation between arms and that the next war would be one of manoeuvre.

Unlike many staff officers, von Seeckt was well travelled and had been educated at a secondary school in Strasbourg rather than in a military school, which probably endowed him with more flexibility of mind than the traditional unbending military education. His work from 192026 resulted in the publication of a pamphlet, Fhrung und Gefecht (Command in Battle), which emphasised the importance of movement in battle. He wanted an army which was only big enough to counter a surprise enemy attack. The real strength of this new army would lie in its mobility which would be provided by a large contingent of cavalry, physically well-conditioned infantry, and a full complement of motorised or mechanised units, machine guns and artillery. Of course the men of the Reichswehr were already battle-hardened, experienced fighters. All he had to do was train them to exploit their mobility.

Von Seeckts work was of such importance that, from 1923, the German army began to base its training and exercises on his published theories, and although the army had very few men to put on the ground in exercises, the basic elements of his ideas became fundamental to German strategic and tactical thinking. The emphasis was rapid reaction to new events, together with a preparedness for decisive action against the enemy. Exercises and manoeuvres from 1923 to 1926 showed how the concept of this war of movement was also becoming standard thinking in the German army right down to section level.

Although von Seeckt had retired by 1933 when Hitler and the NSDAP came to power, his legacy to the German army had not been lost. Hitler was elected on 30 January 1933, under the critical eye of Field Marshal von Hindenburg. Hitler intended to enlarge the army to further his expansionist aims in Europe, and the army was naturally delighted. Senior officers believed Hitler could be controlled: nothing, however, could have been further from the truth.

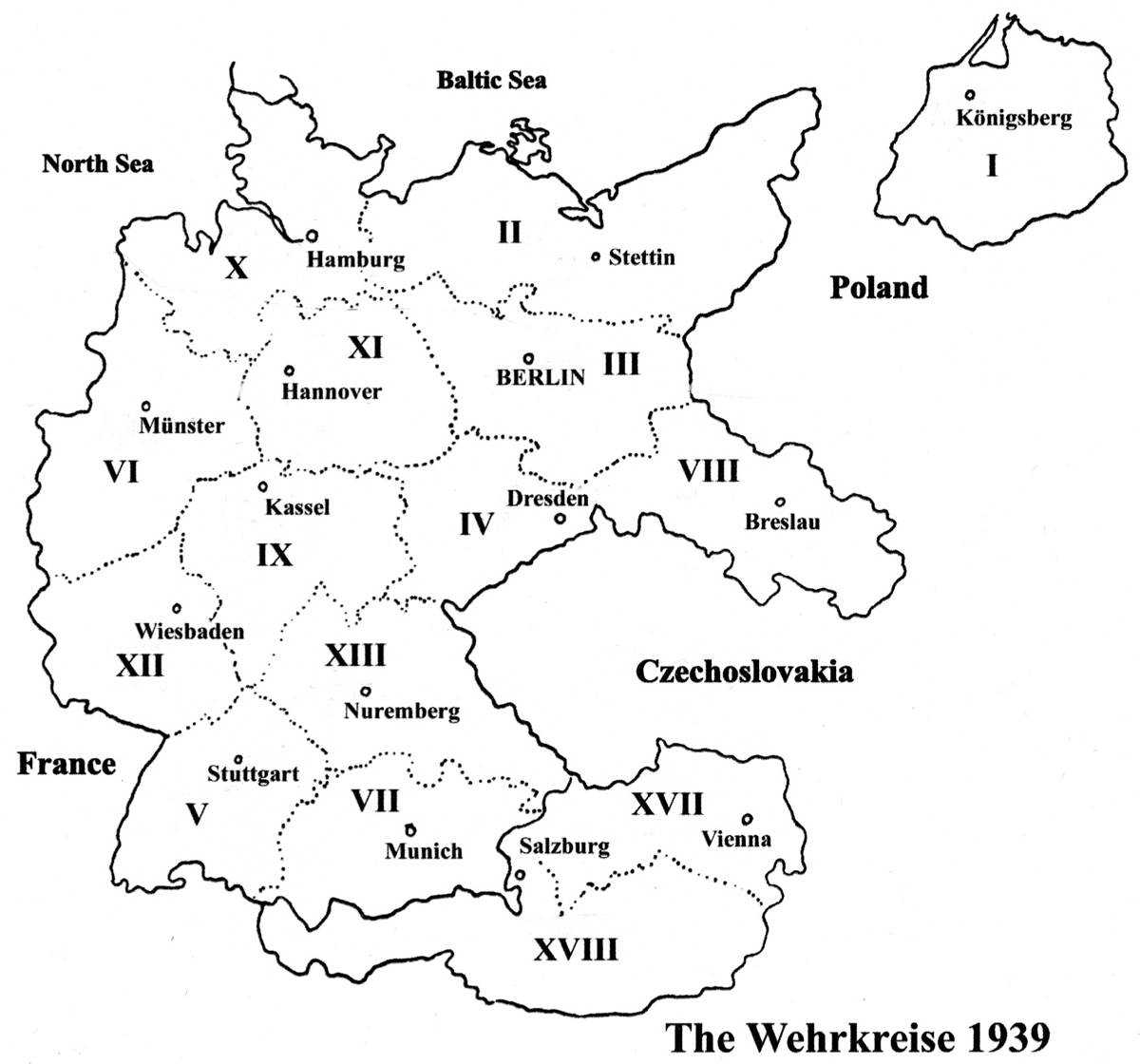

The military districts (Wehrkreise)

Germany had been divided into military districts for recruitment purposes since before the First World War. Each district recruited and trained the men for the army, and within each district there were the relevant corps headquarters, barracks and training areas needed for the Reichswehr. On Hitlers accession he made it quite plain that the army was to expand from the original seven divisions to a total of 36 divisions in 13 corps. The armys initial reaction was one of total surprise, as they contemplated the sheer logistical problems of such enormous expansion. However, they were delighted to be free of the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, with the army assuming an honourable position within German society once again.

Next page