Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the individuals and organizations that have shared their time, knowledge and passion for history. This book could not have been constructed without their help.

Anthony Adamsky

Jacques Bouvier

Paul Campbell

Louis Carbone

Randall Cook

Bruce Decker

Holly Decker

Brian Dugrenier

Betty Gast

Anne Hambucken

Mike Hashem

Kermit Hummel

Ben Kierstead

Michelle Landry

John Warner, IV

Special thanks to Bill Gast of the 743rd Tank Battalion

Gordon Hatch of the 6th Armored Division,

and Harold Ward of the USS San Francisco

2013 by Denis Hambucken. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

Photographs, illustrations, book design and composition by Denis Hambucken Editing by Lisa Sacks

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

American Soldier of World War II

ISBN 978-1-581-57200-1

ISBN 978-1-581-57696-2 (e-book)

Published by The Countryman Press, P.O. Box 748, Woodstock, VT 05091

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Printed in the United States of America

The Collision Course

Before World War II, American society was firmly framed in patriarchal and religious traditions that promoted simple ideals of conformism, respect for authority, hard work and patriotism. This attitude was reinforced by the decade-long Great Depression that imposed a culture of frugality and fortitude.

The Great Depression had spread to Europe. Germany, whose national pride and economy had not yet recovered from the defeat in World War I, was particularly hard-hit. Social and political turmoil fostered radical views that soon installed Adolf Hitlers fascist regime in power. Tensions in Europe increased as Nazi Germany underhandedly annexed Austria, then invaded Czechoslovakia. In response to the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany.

As France and Great Britain prepared for a defensive war along the Maginot line, Germany enjoyed a string of spectacular victories. Poland, Denmark, and Norway were overrun one after the other. Threatened with encirclement, the British Expeditionary Force barely escaped from continental Europe at Dunkirk, as France, Belgium and Luxembourg fell in turn.

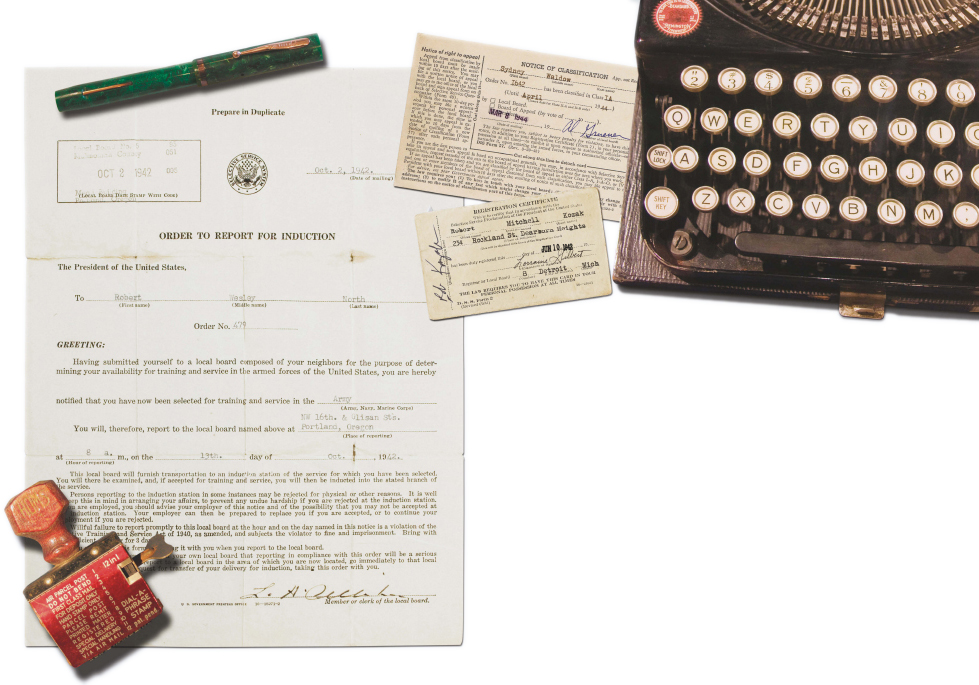

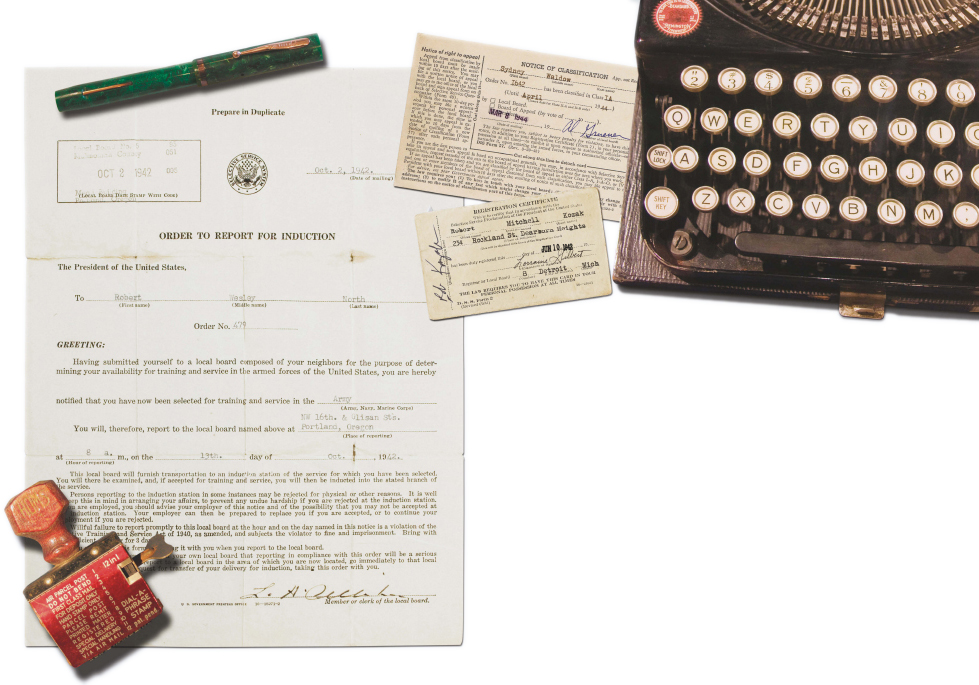

The American public, preoccupied with its own economic struggle, watched the first two years of the war in Europe from a safe distance. Public opinion was dominated by an isolationist sentiment. The resurgence of old European rivalries reinforced the cynical view that Americas costly intervention during World War I had been for naught. It was deemed prudent, however, to bring up the strength of the U.S. military. In 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act into law. It required men between the ages of 21 and 36 to register for a pool from which a certain quota of draftees were randomly selected for military service every year.

In the Pacific, a different sort of trouble had been brewing. As an emerging industrial power, Japan was increasingly competing against European nations and their colonial empires in East Asia. The biggest threat to Japans economic development was its lack of domestic natural resources such as steel and oil, which it imported almost entirely from the United States. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria and continued to push westward into China. In response to the attack on French Indochina in 1941, the United States imposed a steel and oil embargo that amounted to a stranglehold on Japans industrial output. At risk of losing face, Japan set out to rid itself once and for all of its humiliating dependency on foreign resources. The plan included a preemptive strike on the powerful American Pacific fleet based in Hawaii and in the Philippines, followed by the invasion of the resource-rich British Malaya and Dutch East Indies.

The Making of a Warrior

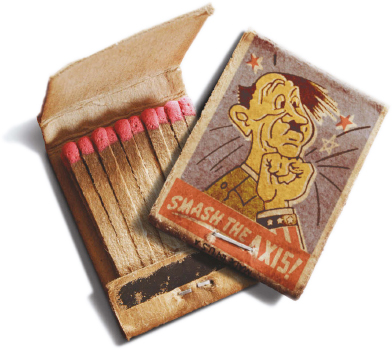

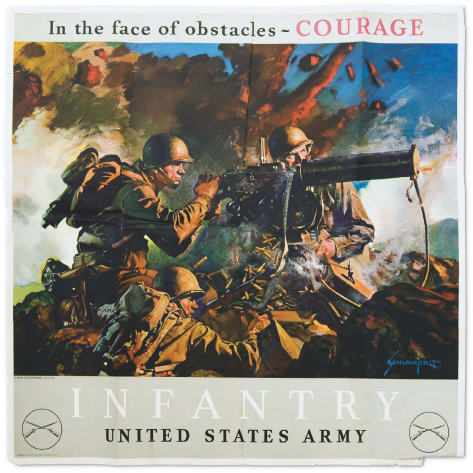

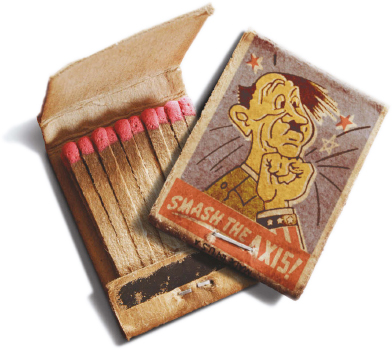

The Japanese surprise attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, threw the United States into the war against the Axis, a military alliance that included Germany, Japan and Italy. But it would take several years to bring up the U.S.s fighting strength to a level that could ensure winning campaigns on several distant fronts. In a rush to expand and upgrade its armed forces, the U.S. government issued countless military contracts for everything from combat boots and uniforms to airplanes and battleships. The result was an unprecedented upsurge in Americas industrial output. Public opinion campaigns and community-based programs capitalized on the publics fear and anger and soon set a tone of optimism and confidence. To the slogan Remember Pearl Harbor, Americans flocked to sprawling war plants where tanks, bombers, ammunition and other military equipment was produced on a prodigious scale. Private and public organizations of every kind sponsored war bond sales and war materials scrap drives. The draft system was extended to men between the ages of 18 and 45. Aggressive recruitment campaigns exhorted a sense of patriotic duty and played off young mens timeless fascination with weapons and military life. Rather than waiting for the draft, many men volunteered because it gave them a chance to apply for the branch of service they preferred.

News of a young mans induction came in the form of a letter from his local draft board mandating that he present himself at a specific time and place. From there, he was directed by bus or train to a regional induction center. Inductees were indelicately examined by medical personnel. Then came interviews, forms and questionnaires. To be deemed fit for service, a young man had to be between 5 ft. and 6 1/2 ft. tall and weigh at least 105 pounds. As many as 30 percent were rejected based on physical or mental deficiencies including illiteracy, chronic diseases, hernias, malformations or vision impairments. Also excluded were the men who claimed that they did not like girls. While a small minority of men did their level best to be rejected, being deemed unfit for duty under the classification 4-F carried a social stigma. Men unfit for service were often derogatorily referred to as F-ers and many were unfairly harassed. Those selected for service were usually given the opportunity to return home for a few weeks to put their affairs in order in preparation for a long absence.