Prologue

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF COFFEE

Many years later, Jaime Hill would think back to the afternoon of his kidnapping and blame his father. It was late in the day on October 31, 1979, and Jaime had just settled at his desk to write to his daughter Alexandra. Even so, Halloween paled in importance next to the upcoming Day of the Dead, celebrated at the beginning of November, and marking the start of the harvest season.

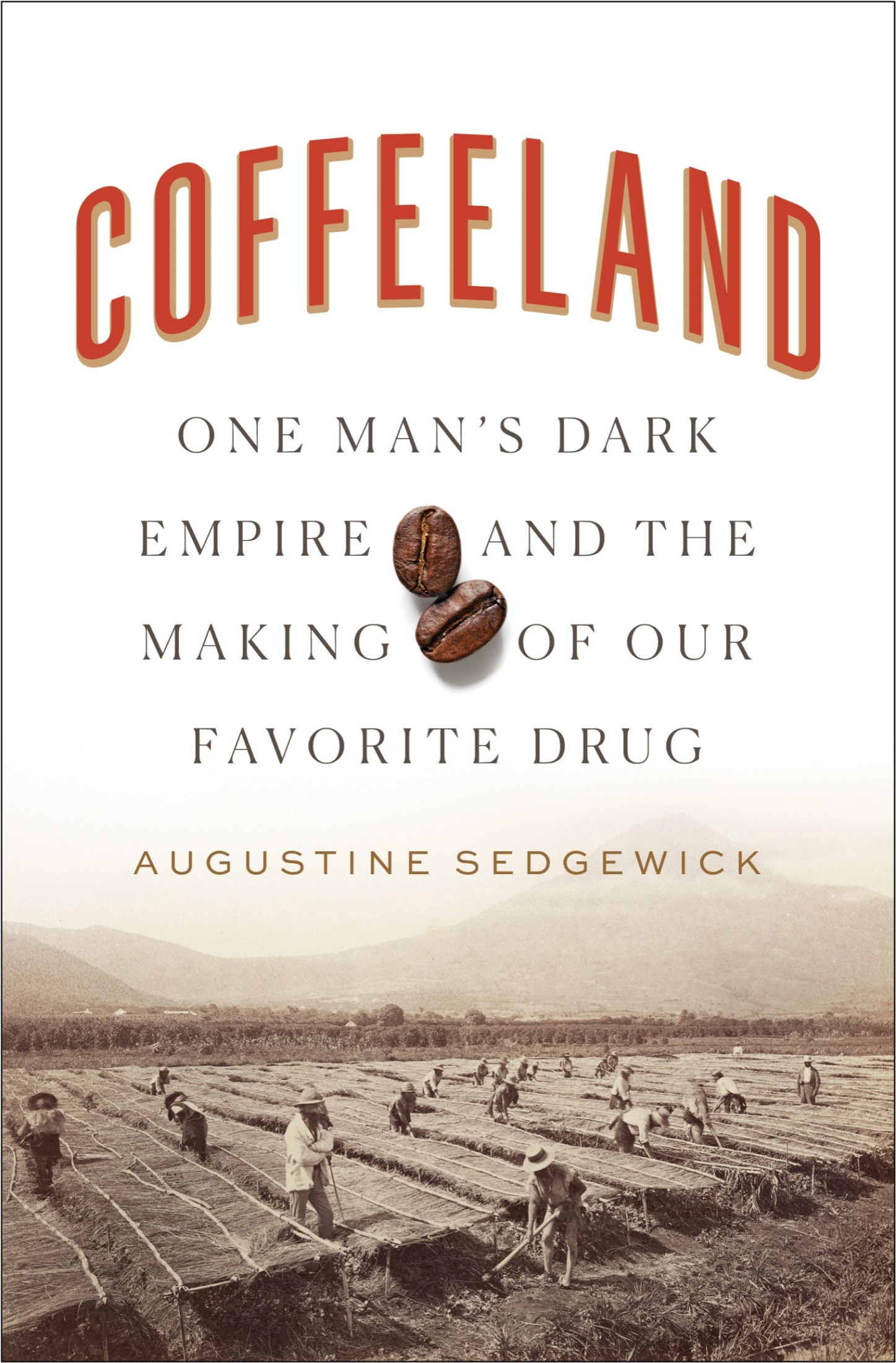

Jaime always looked forward to the harvest season, when six months of steaming downpours finally gave way to blue skies and cool breezes, and his excitement said a good deal about the countrys history. Lacking an Atlantic coastline, El Salvador had been something of a backwater when it won independence from Spain in 1821a land of subsistence farmers with four lawyers and four physicians among its 250,000 citizens. Only two or three ships a year called at its primary port. They had little incentive to produce new and unfamiliar cash crops for distant markets, and even less to work for someone who did. Traditionally, the regions subsistence farmers dreaded the arrival of the dry season. Every November, with months of drought ahead, Salvadorans, like their neighbors, prayed for the return of the rains on which they depended.

Deep into the nineteenth century, life for many people in the Salvadoran countryside went on much as it had for hundreds of years. As the sun came up, men carried farm tools along narrow dirt paths that ran from small villages to remote garden plots, and when work was done they returned home with whatever was ready to eat or sell in local markets.

Yet there were also those Salvadorans for whom this deep continuity with the past was not a comfortthose who looked out into the wider world of combustion engines, telephones, and electric lights and feared their country was falling behindand this group wielded disproportionate political power. Subtly at first, but then radically after 1879, the agrarian foundation of Salvadoran life was uprooted to clear the way for a different future.

By 1889, when Jaime Hills grandfather James, then a young man of eighteen, arrived in El Salvador from Manchester, England, a profound transformation was under way. Within two generations, El Salvador was a different place. The first thing that strikes the visitor, wrote an American traveler in 1928, is the apparent unanimity of thought: COFFEE. Everything is coffee, everyone is directly or indirectly engaged in coffee. Salvador is a country which should live as a unit with but one theme, a single subject: COFFEE, said the Salvadoran minister of agriculture, a coffee planter himself, in the same year.

Though he settled in El Salvador a decade into the coffee boom, and though, as an immigrant, he was barred from holding political office, James Hill arguably did more than anyone else to transform his adopted country into one of the most intensive monocultures in modern history. By the second half of the twentieth century, due in part to practices Hill introduced on his plantations and in his coffee mill, coffee covered a quarter of El Salvadors arable land and employed a fifth of its population. Salvadoran plantations generated per-acre yields 50 percent higher than Brazils, producing an annual coffee crop that made up a quarter of the countrys GDP and more than 90 percent of its exports. Significantlyand due in part, again, to relationships Hill helped to forgemost of those exports ended up inside brightly colored tin cans lining supermarket shelves in the United States, which had, over the same period, become far and away the worlds leading coffee-drinking country. In a century, the harvest in El Salvador had taken on a new meaningpicking and milling coffee bound for American cupsand its bounty had changed hands.

I N THE H ILL FAMILY , as a result, the start of the coffee harvest normally meant rewards close at hand, but 1979 was not a normal year. The weather, as usual, had changed right on time, bringing sunny skies and dry air ideal for picking and milling coffee. Yet these favorable conditions were clouded by developments within the family and in the country at large. Jaime, the oldest of three brothers, had recently been demoted from his position in the family business, which had expanded since World War II from coffee into real estate, construction, finance, and insurance. More troubling, the renewal of old political conflicts had put the success of the years harvest seriously in doubt.

One hundred years of coffee had split El Salvador in two. At the same time as the country had achieved extraordinary levels of economic productivity, it had also become poor in the most fundamental ways. Eighty percent of the nations children were malnourished. Extreme poverty, once nowhere to be seen, had become one of the two basic facts of Salvadoran lifethe other being the extraordinary wealth of the legendary Fourteen Families, including the Hill family, who had started in coffee and kept going until they achieved a near monopoly over the countrys land, resources, economy, and politics. There was the oligarchyeducated abroad, driven around in the backseats of armored European cars, their power in business and government secured by the military, private bodyguards, and high walls around their gated homesand there was everyone else. The fracturing of El Salvador into very rich and very poor had not gone unchallenged, but historically opposition to coffee capitalism had met fearsome repression, and for a time the popular resistance, once fearsome in its own right, had been driven underground.