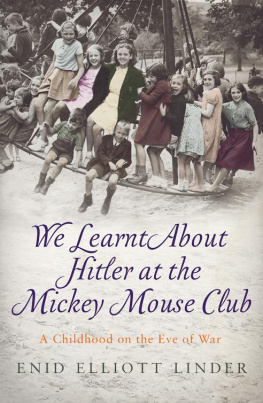

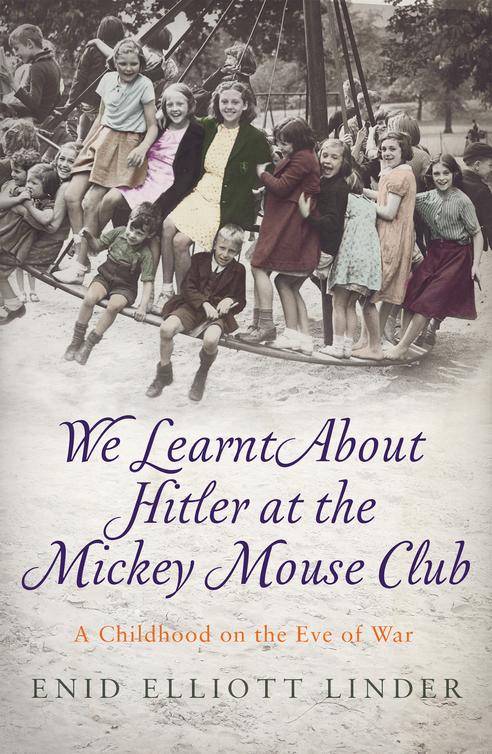

Enid Elliott Linder - We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club

Here you can read online Enid Elliott Linder - We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Icon Books Ltd, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club

- Author:

- Publisher:Icon Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

All illustrations are originals by Enid Elliott Linder, drawn for this book

viii

I n the summer of 1932 most people in Great Britain had never heard of Adolf Hitler. The sun was still shining brightly on the British Empire and the days seemed long and golden, especially to a four-year-old child like me. My two-year-old sister and I lived below stairs with our parents in the servants quarters of an ancient riverside mansion in Richmond. Our father was the butler there and our mother was the cook.

Memories of that time and place still come echoing down through all the years to haunt my mind. I see once more the forbidden garden and hear again the droning of bees in the tall roses, the sound of water splashing from a bronze fountain and the laughter of two exotic children who had come to stay in that imposing residence by the river, quite unaware that there were two other children living below them in the deepest and most hidden part of the house.

Queensberry House, which has long since been pulled down, stood with its feet almost in the water beside the River Thames, just a few hundred yards downstream from Richmond Bridge. Our bedroom was in the many-corridored, gaslit, stone basement, where daunting shadows lurked in every corner. It was a place just made for ghosts, particularly when white mists wreathed in from the river, turning the lofty trees, the wooden boathouse, and even the old coach houses tucked away by the courtyard into vague and eerie shapes. Images or reality; the line between them is flimsy like a veil.

Something happened there, in Richmond, that summer, that was to change the course of our lives. A strange sequence of events played out under the bluest of skies, in an England that has gone and can never return.

Our father was a tall man with a good figure and bearing. His hair was almost as dark as our mothers but was wavy at the front. He had blue eyes and the sort of smile which made you feel warm and important. When he was not on duty upstairs he played with my sister and me a great deal and made up funny stories for our delight. From our earliest days he regaled us with rambling tales of his own youth and boyhood it was almost as though he was surprised to find himself grown-up, and was still wondering how he had come to be changed from a jolly country boy into a mannerly and dignified butler. Coming down through the service lobby dressed in his tails and with his upstairs face still in place, he was a different man altogether.

Our mother did not look at all like a cook, even when she was dressed in her highly starched white coat-overall and apron, handling her ladles and wooden spoons with expertise. Her eyes were dark and thoughtful, her skin was pale and cool, and she wore her glossy dark hair cut in a fashionable bob. She was gentle and petite. She was also quietly studious, teaching me to read at an early age and taking time to answer my innumerable questions. Like my father, she had been a farmers child, but had been orphaned early in life. She had been put into private service by the orphanage when she was fourteen, despite the fact that her bright intelligence had earned her the chance to become a pupil teacher.

My sister, Joan, spent quite a lot of her time when she was young corralled in a wooden playpen in a corner of the huge basement kitchen. There in the rosy shadows between the gleaming fire range and the tall wooden dressers, she would amuse herself for hours with her wooden alphabet bricks, a sawdust-filled doll with orange hair, and a chewed cardboard book full of yellow lions and tigers and people waving union jack flags. She had velvety brown eyes, honey-coloured hair which went curly in the rain, and dimples. The kitchen maids, and even the smart-as-a-pin housemaids were always picking her up and cuddling her, risking their starchy caps being pushed askew and their stiff white collars being dribbled on in the process of receiving one of Joans soft baby kisses.

I had green eyes and freckles and very dark straight hair which never did anything interesting. I had long legs like Father, long eyelashes like Mother and, whenever I was thinking deep thoughts, an expression on my face which caused maids to remark: be careful now if the wind changes youll get stuck like that!

In the early days I sometimes heard our mother say to people: what a blessing Joan has always been such a good baby. Heaven knows what we would have done otherwise. I would feel a little put out on hearing this, for nobody ever remarked on my goodness. To a child who was bursting with curiosity, living below stairs in a world peopled almost entirely by busy servants, and where there were numerous forbidden doors and secret stairways, the achievement of staying good always required a great deal of self-restraint on my part.

My mother would sometimes let Joan play with a wooden spoon and two or three of the jelly moulds made of shining copper, which were shaped like fish or rabbits or castles. They normally lived on one of the dresser shelves. In that big, busy room the noise my sister made with them could hardly be heard: it seemed to drift to the top of the arched stone ceiling and get lost up there. The ceiling stones near to the fireplace end were all blackened. My mother thought the stain had probably been caused by rising smoke and fatty steam from days, long gone, when sides of meat had been cooked there on a roasting spit. A number of curious pieces of black metal and little wheels were still fixed in place in the wide chimney and on the chimney breast.

Each of the high wooden dressers could hold a full dinner service on the lower shelves. The drawers and cupboards below stored all the cooking crockery, baking equipment and other large utensils. On rainy days I was sometimes allowed to tidy out the dresser drawers, or, at least, the shallow ones. A space would be cleared for me in a quiet corner of the scrubbed stone floor and I would lay out, in order, all the jumbled-up bits and pieces that were so necessary to the running of the kitchen but were difficult to keep tidy: things like piping-bags, corks, string for trussing birds and rolls of meat, metal meat skewers, wax candles and pudding cloths. In other drawers were bunches of keys, tradesmens order books, indelible pencils, bills and invoices and a box of white chalks. The chalks were used for writing on the flagstones near the fire, the times when certain pots should be removed from the boiling end and drawn aside to simmer. Sometimes there would be chalked messages saying things like DO NOT BANG, when there were souffls in the oven.

But my favourite indoor occupation was to sit perched up on a high stool, with a cushion on it, at a corner of the long, scrubbed kitchen table, and either draw pictures of what I saw, or just watch my mother cooking.

One morning, when I was doing this, I became aware that an unusually large number of staff and other people were gathering together in the kitchen. Even the housemaids, who usually spent so much of their time looking after the mysterious kingdom upstairs, were down in the kitchen with us. The kitchen maids were present, naturally, because they belonged there. One of them, with floury forearms, was carrying on making pastry while the other was turning the handle of the mincer with her right hand and pushing a cold saddle of mutton into it with her left. I knew that later on three big mutton pies for the servants hall would emerge from the oven. Then I saw the scullery maid emerge from her steamy den with her red hands hidden under the brown sack-cloth of her outer apron. Thomas and William, the footmen, were there in their shirtsleeves and aprons, having just come from washing glasses in the pantry. The chauffeur, also in his shirtsleeves, had come in from hosing down cars in the cobbled courtyard. His wet wellingtons stood side by side on the kitchen doorstep and beside them in a neat row, stood several pairs of gardeners boots: the head gardener and his men had come into the kitchen in their socks. There were even two tradesmen standing over by the fire range. They wore loose, fawn, linen coats over their black three-piece suits. They had come to enquire about orders and stayed to drink tea. Their bowler hats hung on the coat rack behind the door.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club»

Look at similar books to We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book We Learnt About Hitler at the Mickey Mouse Club and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.