IRVING BERLIN

Irving Berlin

New York Genius

James Kaplan

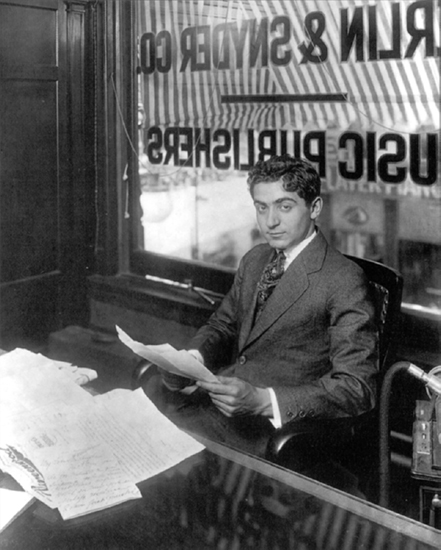

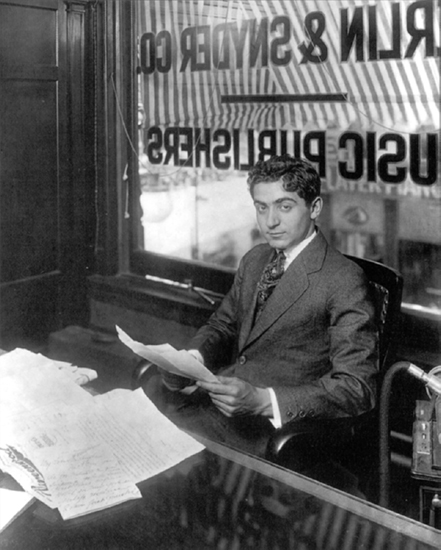

Frontispiece: Portrait of the artist as a young titan. Just twenty-six, Berlin is immensely successful and powerfulbut his bold gaze disguises deep self-doubt. Irving Berlin Music Co.

Copyright 2019 by James Kaplan.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations,

in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the

U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press),

without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail

(U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions,

Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019933153

ISBN 978-0-300-18048-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is for Peter W. Kaplan and Peter Bogdanovich

Irvy writes a great song. He writes a song with a good lyric,

a lyric that rhymes, good music, music you dont have to dress

up to listen to, but it is good music. He is a wonderful little

fellow, wonderful in lots of ways. He has become famous and

wealthy, without wearing a lot of jewelry and falling for funny

clothes. He is uptown, but he is there with the old downtown

hardshell. And with all his success, you will find

his watch and

his handkerchief in his pockets where they belong.

George M. Cohan

_________________

He doesnt attempt to stuff the publics ear with

pseudo-original, ultra modernism, but he honestly absorbs

the vibrations emanating from the people, manners, and life

of his time, and in turn, gives these impressions back to

the worldsimplifiedclarifiedglorified.

In short, what I really want to say, my dear

Woollcott, is that Irving Berlin has no place in

American music. HE IS AMERICAN MUSIC.

Jerome Kern, in a letter to Alexander Woollcott, 1925

_________________

It must be hell being Irving Berlin. The guys

his own toughest competition.

Anonymous music publisher

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A BORN NEW YORKER, I first discovered my fellow Manhattanite Irving Berlin during the sliver of time in which we both occupied the same city. It was during the mid-1970s, when, as a very young man, I worked as an editorial typist at the New Yorker, while that august institution was still ensconced in its ramshackle original offices, built in 1925 at 25 West 43rd Street. The city, too, had a ramshackle air about it then: it was, famously, a period when New York was broke, and Manhattan, in those days before it became a cold and glass-faced digital video game, was a gritty, graffitied place, a town that couldnt yet afford to efface its links to the past. Every morning, rain or shine, I walked the three-odd miles from my apartment at 106th and Riverside to Midtown, amid traces of an older and slower New York: ancient painted signs, faded but still visible, on the brick sides of buildings (OMEGA OILSTOPS PAINTRIAL BOTTLE 10); a blind accordionist on a Broadway corner; a 1920s-vintage barber shop at the top of Sixth Avenue where it was still possible to get a straight-razor shave. It was a time when, strolling into the Hotel Algonquin or Brooks Brothers or Grand Central, you could squint and imagine yourself in a city of Elevated tracks and black automobiles and, of course, the blue nimbus of cigar and cigarette smoke hanging over the island like a low-lying front.

The ghosts of Manhattan past were even more palpable in the hushed linoleumed halls of the New Yorker, where the cream-colored walls themselves seemed to hold secrets of the magazines early daysliterally, in the case of James Thurbers old office on the eighteenth floor, which retained cartoons, penciled right onto the plaster, of leaping dogs and doughy, baffled-looking men. In warm weather, fans whirred throughout the non-air-conditioned offices; windows were thrown open to the sounds and smells of the city. In the halls one could spot dinosaurs like Rogers E. M. Whitaker and Geoffrey Hellman and S. J. Perelman drifting by; now and then there was even a glimpse of the small and flushed presiding eminence, William Shawn, flitting past like a rare ruby-throated vireo. Silently, of course. Silence was overarching at this great institution; the hard work of turning out a magazine every week proceeded in deep quietude, punctuated only by the faint clacking of typewriters.

As a rule the half dozen members of the typing pool barely spoke to one another, let alone socializedit was assumed, though never said outright, that we were all jockeying for higher positions at the magazine, the true brass ring being publication. I usually ate lunch solo, sometimes taking a turn around the block afterward. Now and then, though, I got no farther than the small, sedate record shop adjoining the lobby of 25 West 43rd. Music Masters was its name.

This too was a hushed place, a temple to classical music and classic popular tunes, collected and reissued on Music Masterslabeled LPs, which were sold in severe but elegant black album sleeves. Like record shops of old, the store had a glass-enclosed listening booth, and the proprietors, two bald middle-aged men with clever expressions, exuded a sense of high purpose, as did the browsing communicants. Though the place fascinated me, I felt like a rank outsider. I knew a little classical, a little more BroadwayId grown up with parents who listened to show tunes along with their Bach or Berlioz or Beethovenbut my musical tastes generally comported with my era and my hormones, running to rock, blues, and folk: Dylan, the Beatles, the Stones.

On the other hand, I felt the pull of the past, and had a young mans fascination with old age. I had a grandfather, still alive, who had been born in the late 1880s: I sometimes asked him about New York at the turn of the century; he preferred to talk about the Mets. The twentiesonly fifty years past then, after allwere much in the air. As at the New Yorker, it was a time when great artistic figures of that decade still walked among usEubie Blake, George Burns, Nadia Boulanger, Henry Miller, and Josephine Baker; the pianists Arthur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz. At the West End Caf I attended a performance by a spry and smiling Papa Jo Jones, who had begun drumming with Walter Pages Blue Devils in Oklahoma City in the 1920s; at the Cookery I was enthralled by the regal Mary Lou Williams, who had played with Duke Ellington as a teenaged sensation in 1924. The continuance of these ancients blended with my own youthful sense of immortality to induce, in my spirit if not my intellect, a soaring hope of deathlessness.

As if to close the argument, there was Groucho Marx, in turtleneck and tam-o-shanter, on the Dick Cavett ShowGroucho, who had begun his vaudeville career before World War I, who had starred with his brothers Chico, Harpo, and Zeppo in The Cocoanuts

Next page