As ever we would like to express our thanks to a number of people for their help, support and friendship throughout the writing of this book, this one more than ever: Elizabeth and Paul, Hanako and Gavin and our wonderful godchildren Marika and Hiroki, Alastair, Keith and Hill, Martin and Rosy, John and Elli, Fan and Jessica, Graham and Kirsty, Yoshiko and David. Our love and thanks to Tony, Christine and Marc, and to Truus.

Our sincere thanks to Mr Joshi and all the amazing doctors, nurses, staff and paramedics at UHCW, especially Ward 43, without whom this book would only have one author. And special thanks to Dr Gavin Farrell for getting us through the times in between and beyond.

Many thanks to all those involved with the production of this book: Hannah Patterson, Anne Hudson, Elsa Mathern and Ion Mills. Thanks also to Manga Entertainment for supplying material for review.

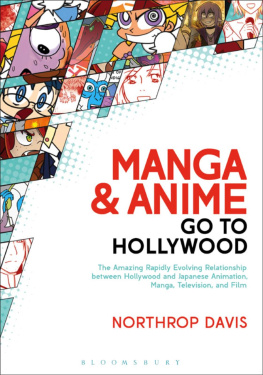

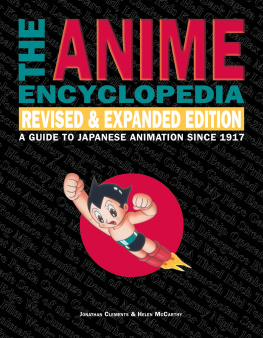

Japanese animation, or anime, is an art form that has been gaining popularity across the globe and has altered the way that we view and appreciate animated film. Traditionally, the perception of animation in the West is that its aimed at children and family markets, through the films of Disney or Pixar and the television cartoons of Hanna-Barbera and Warner Bros Looney Tunes. Although many animations have been created for adults by directors such as Max Fleischer, Ralph Bakshi and Norman McLaren, as well as Eastern European directors such as Jan Svankmajer, Jiri Trnka and Walerian Borowczyk, feature films were not common in the mainstream and animation generally remained in the realm of the experimental or art-house sectors. There is, of course, a large childrens market for anime, but what is so exciting about the format is its diversity. Animes subject matter can range from imaginative fantasies to comedy, drama, horror, sport, science-fiction, romance, avant-garde and erotica and is aimed at audiences that encompass all demographics, from schoolchildren to salarymen.

The term anime is most often used in the West to describe a particular style associated with Japanese cel animation, but in Japan it refers to all animation. Closely associated with anime is manga and, although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably in Western media, they refer to different things. Anime are animated films of Japanese origin. The term comes from the Japanese fondness for condensing words, in this case animation. Manga are Japanese comic books. Both manga and anime are hugely popular in Japan the industry is worth billions of dollars and have been for many decades.

Manga used to be regarded as something for children until they were around 15, manga critic Haruyuki Nakano told Kyodo News on the fiftieth anniversary of two of Japans pioneering weekly manga titles. But baby boomers in post-war Japan kept reading their favourite manga even after they entered college and became adults. That helped make manga widespread in Japanese culture.

There is now increasing awareness and appreciation of both anime and manga in Western countries. This book aims to provide an introduction to anime, exploring its origins as an art form as well as introducing key animators and a selection of works for viewing. Names are presented Japanese style, with family name followed by given name. Romanisation of characters is via the modified Hepburn system, with macrons to emphasise double-length vowels, except where the word is in common usage in the English language, e.g. Tokyo instead of Tky.

ORIGINS OF ANIME

Japan has a long tradition of art and literature. During the Heian period (7941185), e-maki (picture scrolls) became established as an art form. Mainly created during the twelfth century, these beautiful illustrations depicted scenes of court life or historical events. The origins of the Japanese art aesthetic can be seen in these scrolls. During the Edo period (16001868) woodblock prints became incredibly fashionable. These were pictures created by artists and transferred onto a woodblock whereupon craftsmen would carve away at the wood to produce a relief of the image, in reverse. This could then be inked and printed to reproduce copies of the original drawing. Multiple blocks could be produced to create multiple colours, sometimes with several inkings to obtain a greater depth of hue, and the finished product could be reproduced quickly and in large quantities. It was a collaborative process that can, in some respects, be likened to the production of anime whereby the writer, director and key artists determine the creative element of the narrative and design, after which artists and in-betweeners generate the final product. Woodblock prints were easy to reproduce and cheap, which meant that they were very accessible and could be distributed widely. Sometimes a series of popular prints would run to hundreds of thousands of copies. Its similar to the distribution of manga today multiple copies printed on low-grade paper and sold cheaply to the public (the price of the woodblock prints could compare roughly with a double helping of soba noodles; manga sells for the equivalent of just a couple of dollars), who are constantly waiting for the next episode in the series. The primary market for these prints generally comprised the lowest ranking of the social hierarchy of the time merchants and artisans although the prints were also appreciated by the samurai classes. Known as ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world, these woodblock prints depicted beautiful landscapes, everyday life from the Edo period, pictures of animals and flowers. Particularly popular were the prints from the pleasure quarters, of geisha and tea-houses, as well as kabuki (classical Japanese drama) actors in famous roles.

The aesthetic style of ukiyo-e is a world apart from Western art of the time. The images are bold and colourful. It is said that the Japanese favour symbolism over realism. One of the most distinctive elements of traditional art is that it is very flat there is a distinct lack of perspective or shadow and a very different approach to composition with the main focus of the image often off-centre. This design aesthetic can be seen in many anime right up to the present day.

The leading woodblock artists were Katsushika Hokusai (17601849), Utagawa Kunisada (17861864), Utagawa Hiroshige (17971858) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (17971861). (The Utagawa name comes from the famous woodblock print school.) Incredibly prolific, Kuniyoshi produced over 10,000 pictures over the course of his career. He produced a variety of images, but made his name with his series, One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Suikoden (Tszoku Suikoden gketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori), based on the classic Chinese tale, known in the West as The Water Margin. This series of prints featured dynamic designs of the heroes of the story and was enormously popular. The term manga was first used by Hokusai (best known for his print The Great Wave off Kanagawa, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji) to describe his 13 volumes of sketches. The term can be translated as whimsical drawings. Since then, the name stuck and has been used to describe Japanese comics. Hokusais manga did not take the form of a comic book as we know it today, but were simply collections of sketches and caricatures, many of which were humorous. Modern manga developed in the years following the Meiji restoration (1868) and notably after the Second World War (when Japan was occupied by the US), reflecting the influence of American culture particularly comic books and movies on Japanese society.

Akahon, literally red book, named for their vivid red covers, originated in the Edo period and were originally childrens books. Produced in a way that was similar to the making of ukiyo-e (the artist would produce the image, then craftsmen would copy that image onto printing plates), akahon were printed on cheap paper and covered a broad range of subject matter. They were hugely popular during and after World War Two because they were an affordable form of media. They also gave emerging artists an opportunity to create and distribute their stories. It was originally through the production of akahon that a young medical student, Tezuka Osamu, got his first break as an artist with