skirt! is an attitude... spirited, independent, outspoken, serious, playful and irreverent, sometimes controversial, always passionate.

Copyright 2013 by Karen Dietrich

The events described in this book are based on the authors recollections. Dialogue has been re-created and names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

skirt! is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

skirt! is a registered trademark of Morris Publishing Group, LLC, and is used with express permission.

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Maggie Peterson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-1-4930-0064-7

For my father, who told me to write books.

Contents

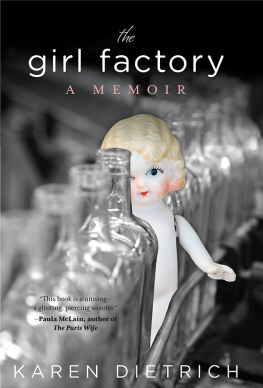

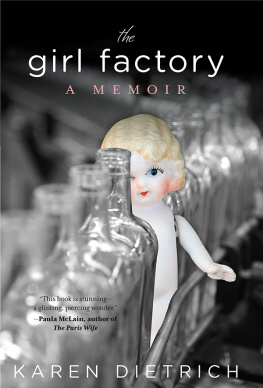

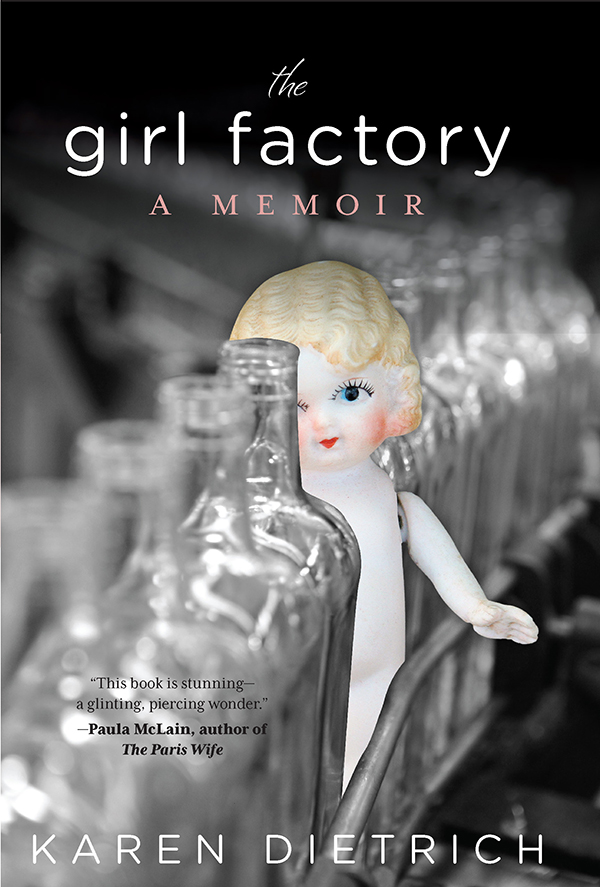

PART ONE

I imagine a place where girls are made. Some roll off the assembly line shiny and wet, wheat-colored hair sewn into their beautiful heads like dolls. Other girls are assembled from spare parts, pieces the glossy girls refusea leg here, an elbow thereour maker scavenging for anything to use. Building girls like me is lonely work, no reward for the journeyman, no bright fame. Inside the girl factory, it is dark as midnight, the workers toiling away, unable to see their hands. There are so many mistakes to be made, which is why I know there must be girls like me out there somewhere. Im the glass thrown onto the cullet belt with a smash. I break into a hundred sharp pieces. The belt leads underground, where girls like me are melted, poured into molds so the maker can try again, try to get it right this time. But I keep coming out flawedcold crizz, chip finish, bird swing. I look whole, yet crumble with a touch. Im thrown back to the cullet, back to the melting pot, where I keep trying to come out right.

CHAPTER 1

Bread and Butter

When I sit perfectly still, the stars seem to dim then brighten like a pulse, a metronome of breathing. My mother is next to me in the grass. I am eight years old and she is telling me about shooting stars. She says if you see one, it means someone you love is about to die. My eyes scan the stars, which are splattered in clumps, as if someone has thrown handfuls of light against the dark. I hope everything stays put for now.

My mother knows a lot about the sky. She teaches me things: where to find the Big and Little Dippers, how to spot Orions belt on a clear night, how to track the phases of the moon. There are rhymes to help me remember certain things. Red sky at night, sailors delight. I spend hours in darkness stretched out in the yard, looking up. My mother says theres a star for every person alive in the world. Thats why you see a falling star when someone dies. The sky doesnt need that star anymore, so the sky sends the star to you.

Are you supposed to catch it? I ask.

Why sure, she tells me, if you can run fast enough. She pulls herself up, gently brushing a few damp blades of grass from her jeans. If you can find the spot where the star fell to Earth, then that person you love wont die after all. She disappears up the back porch steps and into the house, its windows blinking through sheer curtains that sway in the evening breeze.

As long as I can remember, my mother has been teaching me what my father calls Mothers ways . I know to knock on wood when I think about good luck, like never breaking a bone in my body. If I dont, the spirits of bad luck will scold me for boasting, and curse me with a broken ankle or arm, their way of reminding me of my place in the world. If you cant find wood, knocking on your head is the next best thing. Knocking on glass or plastic is actually worse than not knocking at all. There are things you should never do, like break a mirror or use your oven on Sunday or let a bird fly into your house. Then there are things you must do: throw salt over your shoulder after you spill some, shake an empty purse at the full moon, say bread and butter if youre walking down the street with a friend and something comes between the two of you, like a telephone pole or another person.

I have a recurring dream. In it, I am walking alone on a slick black road. There are no houses, no streetlights, no trees, nothing to distract my view of the sky, which is inky blue. It has a texture. If I reach up to touch it, it will feel like corduroy, millions of soft raised rows, perfectly spaced, like cornrows. There is only one star in the sky, and even though no one in the dream tells me this, I know it is because I am the last person on Earth.

All of my mothers family is dead, except for one brother, Jack-Rogers, who lives in Somerset, but she doesnt speak to him for reasons Im not old enough to know yet, so he doesnt really count. My mother had three younger brothers in all: Jack-Rogers, Eugene, and Joseph. Like most people in southwestern Pennsylvania, they had nicknames. Jack-Rogers, the oldest of the three, goes by Roger. Eugene, the middle brother, was known as Boots, and Joseph, the youngest, was called Little Joe. Boots and Little Joe both died in sad ways before I was bornone beaten to death during a drunken fight on a naval ship, one liver-poisoned from too much nerve medicine. I picture my uncle Boots drinking it straight from a brown glass bottle with no label, then counting the money in his sock drawer. My mother says when Boots died, she found two thousand dollars in that drawer, all in nickels and dimes. She talks about Boots and Little Joe like theyre still alive, her eyes moist and shiny, her cheeks suddenly a brighter pink as if blood is trying to pump itself out of her through invisible holes in her skin.

I peel myself from the wet summer grass of our backyard and wander inside the house through the large sliding-glass door. Every night before we go to bed, my mother closes the slider, then puts a stick in the door. Its a piece of broom handle my father cut and shaped to fit in the grooves of the doors sliding track, so no one can break in while we sleep. We call that piece of wood the-stick-in-the-door. We like to name things based on where they belong, like the-pen-by-the-phone, my mothers black Bic ballpoint that lives in a small orange box of scrap paper next to the kitchen telephone. You better not move the-pen-by-the-phone, not even an inch, or there will be hell to pay, even though Ive discovered my mother has entire packages of those pens stashed in the attic.

My father is in the kitchendark blue work jacket, collar up to his ears, his black lunch box symbolizing departure. Hungry cats circle the yellow rug as he makes wax paperwrapped sandwiches, loads small cakes wrapped in cellophane, and stores the Coca-Cola he drinks, a bottle an hour, to stay awake. He is working the night shift tonight at Anchor Glass, the glass factory in the south end of town . I dont say goodbye to him, convinced that if I do he will somehow die before 7:00 a.m., will not return to this brick home on this slanted street, these windows secured with shiny brass locks. I say good night instead, running through my catalog of different ways it can happen: heart attack, explosion, a fall into the furnace. I sleep in bed with my mother when hes gone, check the-stick-in-the-door eight times before I try to fall asleep, listen to our house settle in the night.