CONTENTS

For those whove waited at the dock

and all who ever will

LOST

AT SEA

THE AMERICUS

Crew List, February 1983

George C. Nations, Captain

Age: 43

Experience: 13 years

Next of kin: Janice Nations, wife

| Brent Boles, relief captain | Victor Bass, deckhand |

| Age: 24 | Age: 19 |

| Experience: 4 years, 10 months | Experience: first voyage |

| Next of kin: George Boles, father | Next of kin: Lloyd and Jean Bass, parents |

| Larry Littlefield, engineer | Jeff Nations, deckhand |

| Age: 29 | Age: 19 |

| Experience: 9 years, 2 months | Experience: 5 months |

| Next of kin: Al and Judy Littlefield, parents | Next of kin: Janice Nations, mother |

| Rich Awes, deckhand | Paul Northcutt, deckhand |

| Age: 20 | Age: 24 |

| Experience: first voyage | Experience: 4 years, 2 months |

| Next of kin: Elden and Lois Awes, parents | Next of kin: Eve Northcutt, mother |

THE ALTAIR

Crew List, February 1983

Ronald Biernes, Captain

Age: 47

Experience: 24 years

Next of kin: Nancy Biernes, wife

| Jeff Martin, engineer | Randy Harvey, deckhand |

| Age: 23 | Age: 23 |

| Experience: 2 years | Experience: first voyage |

| Next of kin: Don and Roberta Martin, parents | Next of kin: Richard and Marguerite Harvey, parents |

| Lark Breckenridge, deckhand | Brad Melvin, deckhand |

| Age: 24 | Age: 26 |

| Experience: 5 months | Experience: 3 years, 3 months |

| Next of kin: Kelly Breckenridge, wife | Next of kin: Wayne Melvin, father |

| Troy Gudbranson, deckhand | Tony Vienhage, deckhand |

| Age: 21 | Age: 27 |

| Experience: first voyage | Experience: 3 years |

| Next of kin: Jody Gudbranson, wife | Next of kin: Mary Vienhage, wife |

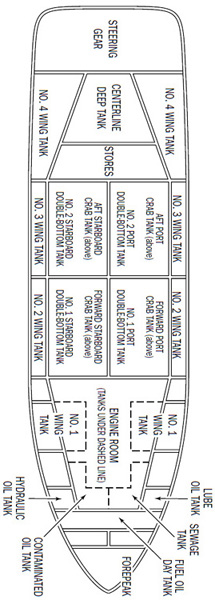

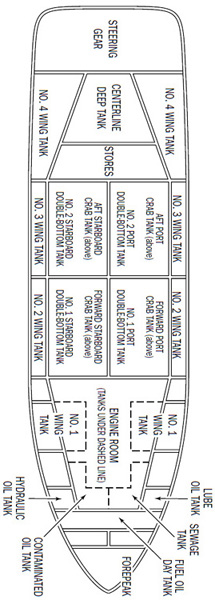

Tank arrangement for the Americus

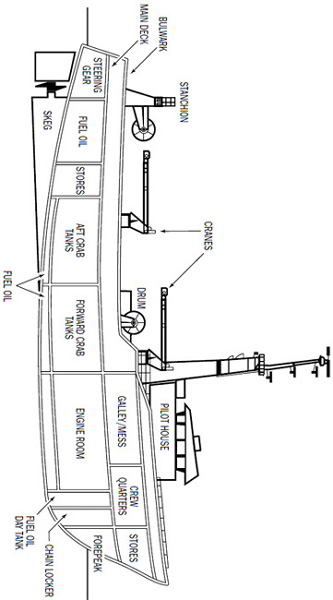

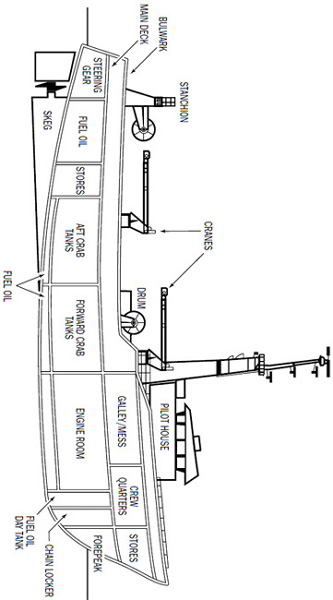

Profile view of Americus with trawling gear

LOST

AT SEA

PROLOGUE

T HE OLD FISHERMAN backed his boat from its berth with ease. When his bow was clear of the vessels moored on either side of him, he feathered the throttle and turned the wheel, making an unhurried pivot to starboard, and headed toward the channel that led to open water. Francis Barcott, seventy-five years old, had been working the water for sixty-one years; his place at the helm of the Veteran was the most familiar in his life. Fishermen darning clean meshes in their nets on the docks called him the Old Man and deferred to him. Years of deliberation were etched on his face, and some sentimentality, too, shaded his eyes. He looked as though he might have aged quickly as a young man and then stopped altogether as the graying years passed by. His hands, though, were thick, hardenedthe hands of a fisherman. Even when relaxed, a fishermans fingers cup rigidly toward the palm in a palsy caused by years of holding tight to gear and pulling lines in the cold and wet.

The Veteran was a stately wooden sixty-eight-foot purse seiner, painted black with a white wheelhouse and a rakish, cleaver-sharp prow. She was built in 1926, when fishing was an alloy of aesthetics and utility, when the way a boat presented herself to the water and how precisely the net was set commanded nearly equal respect with how much salmon a fisherman caught.

Everything Francis knew about fishing he had learned decades earlier from his father. In the summer of 1913, in an open skiff, Anton Barcott had first set his own net on the ebb tide along the Rosario Bluffs near Deception Pass in the northwest corner of the state of Washington. Like thousands of other young farmers and fishermen from the islands of the Adriatic, Anton Barcott had heard of the legendary Pacific Northwest salmon runs. Believing himself to be as good a netman as any, he set out to make his fortune there and was not disappointed.

In the late summer or early fall, when the moon and the tide and currents were right, millions of sockeye salmon would pour from the Pacific Ocean through the Strait of Juan de Fuca into Puget Sound and then race east directly toward the bluffs where the netmen would be waiting. Within yards of land, where the graveled bottom rose sharply, the salmon would instinctively turn left to make their final migratory run northward toward British Columbia and the spawning tributaries of the Fraser River. But the fishermens nets would intervene, their orange corks marking half-mile perimeters, stretching like enormous open arms along the surface, their weighted webs extending downward a hundred feet. Near the nets edge the boats were lined thirty or forty abreast, with thirty or forty more idling, awaiting their turn in line. In peak season fishermen would routinely haul five thousand pounds of salmon over the bulwarks from a single net.

The letters Anton Barcott wrote home to his native Vela Luka, an island village off the Dalmatian Coast of Croatia, were filled with wondrous details of his newfound home on the western edge of America. The fish were even more plentiful than he could have imagined. Some farmers used pitchforks in the local rivers, heaving salmon as they would hay, some used traps hung from wood pilings to intercept the fish in the narrows between islands, and others used horses to haul their nets in the shallow water along the beaches. In every direction the rocky, steep-banked, tree-studded islands with deep, protective harbors reminded Anton and his fellow Croatians that they were as close to home here as anywhere on earth.

The first wave of immigrants had begun to settle in small villages along the coast of Puget Sound at the turn of the century. When he arrived, Anton Barcott chose to live in Anacortes, which had been bustling with industry since the Alaskan Gold Rush of 1889. Located on the north shore of Fidalgo Islandactually a fist-shaped peninsula thrusting westward into Puget Sound and separated from the mainland by the ribbon-thin Swinomish ChannelAnacortes was the closest port to Alaska and the Orient except for Bellingham, fifteen miles to the north. The towns founder, Amos Bowman, a civil engineer and landowner, had heard the rumors about the coming of the transcontinental railway and bet that with its deep water, natural harbor, and easy connection to the mainland, Anacortes could outrival Seattle and Bellingham and even San Francisco as the Wests primary port. He bought hundreds of acres, named the village after his wife, Anna Curtis Bowman, and quickly persuaded lenders and buyers to rally around his plan.

Next page