Brian Dillon

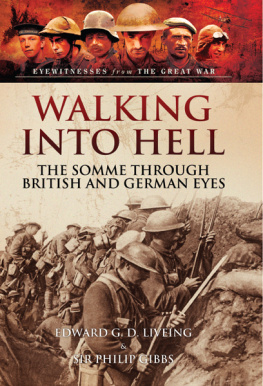

THE GREAT EXPLOSION

Gunpowder, the Great War, and a disaster on the Kent marshes

Contents

For Madaleine, Isaac and Genevieve

I tried to breathe but my breath would not come and I felt myself rush bodily out of myself and out and out and out and all the time bodily in the wind.

Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (1929)

I

THE GUNPOWDER ARCHIPELAGO

Overture

It begins at night, when the machines are idle and the weak sun has sunk into an estuarine horizon.

At first there is little or nothing to see or hear, no clues regarding energies soon to be unleashed on the landscape, on its low buildings and the bodies moving among them. There is a new moon tonight, almost invisible, but the darkness below is not complete, nor the silence. There are lamps behind the windows of some of the buildings, though heavy curtains have been pulled to conceal them, and flashlights regularly probe the more thoroughly blacked-out districts of the marsh. Within certain structures, fires must be kept burning till dawn. There is the sound of heavy boots on wooden boards, scraping on concrete, plashing into wet mud and grass. There are voices low and weary, others cheerful as they drift away towards the deeper darkness at the edge of the site. We may imagine that the voices keep up despite fatigue, if only to ward off other sounds in the night air, with their intimations of wildness and death close at hand the strangely human cry of a she-fox, the barn owls screech that is more like a hiss. In darkness, and without the clamour of work, the place substitutes other sights and other noises, as much of watchfulness and readiness as of the days end.

It is a Saturday night in the second spring of the Great War. Here on the marshes, among the huts and houses that the new workers have learned to call danger buildings, each day is much like any other. Only nightfall brings rest from the tasks at hand: unloading liquids and powders and pulp from boats and trucks, mixing or purifying the noxious mass, draining and sifting and drying. Or, out at the western edge of the factory, pouring and pressing, shaping this poison till it will squeeze into its metal bed and sleep for a while among serried ranks of shells or bombs before being hefted back onto lorries and trams, or down to the jetty. The stuff, so the older workers say and some of them have been here since before the war will strip your hands raw, or turn your whole skin yellow in a matter of weeks; for this reason, the young women who have come to work at the factory in the past year, and at others like it, have become known as canary girls. There is nothing to be done but pull the belts tighter on thick new uniforms and think of the danger money and the men at the front, for whom this redoubled effort, this acceleration of production, was begun last summer. And not think too hard about the fires and worse that locals remember, about rumours and reports from other factories.

When it starts, we may surmise, it is with the merest pop or crackle. Unheard, unseen or, even if noticed, of no very pressing import to those workers who know the place well. Later, at least one witness will report hearing a fizzing sound as he passed by building number 833 in the morning, but by then the process would have been well under way. Tomorrow the small sounds now quickening infinitesimally in this corner of the landscape will grow louder, until at last they gather around them other sounds of voices and machinery and movement, shouts and fast-moving rumours, telephone bells and revving engines. A rush of air and flame and earth, of shredded metal and split timbers. And at length a noise or several, subsumed into one that not all of those present will have time to hear. A sound that is also a force: a solid wave rushing across a flat expanse, a sound that swells among the surrounding buildings, the nearby fields, the boats and jetties of the shoreline, stretches out towards towns and cities, military camps on distant coasts. A sound grown from the seed of this small agitation of the air, here in the dark.

Excursus

New Years Day, and once again I am walking the marshes of north Kent, hoping to summon a few ghosts. It has become a tradition: for the past decade and a half my partner F and I have spent New Years Eve with friends who live out here on the edge of the old gunpowder works the site is now a nature reserve and most years we have all four struck out late in the morning into this lattice of ditches and paths, among stock-still sheep, expensively equipped birdwatchers and certain low scattered ruins that long ago I promised our hosts I would research properly. Today, though, we are happily distracted from our occasional conjectures regarding the events that occurred, some way off to the north-west of our starting point, in April 1916. Our friends three young children are with us, and there are scooters to be steadied on the unevenly gravelled footpath, splashing steps to be counted across the largest puddles and an unseasonable number of flowers to be collected where the path slopes grassily away to drainage ditches on either side. Im amazed, midwinter, to find myself bending down so that the eldest, our goddaughter, aged six in a matter of days, can gleefully blow a dandelion clock in my face.

Our friends live in Uplees House, one of a pair of large detached houses built at the start of the second decade of the twentieth century. This part of the county was for centuries the site of a sizeable military-industrial complex, and for some years the houses were occupied by managers from two of the explosives companies whose buildings and infrastructure had by that time ramified from the nearby village of Oare towards the Swale the body of water that separates the Kent coast from the Isle of Sheppey then along the shore in the direction of the estuary of the Medway River. There was another, much older, works adjacent to Oare, and still another, in fact the oldest, in the local market town of Faversham. Before this landscape and its coastline become visible we have to walk along the narrow tree-lined road that separates the two big houses, past a couple of bungalows on the left and a decayed orchard on the right where in the spring, when the weather turns, a few dwarf sheep (curious, friendly creatures you might from a distance take for lambs) will graze among grey branches fallen from the tall, old-fashioned apple trees. The road narrows to an unfinished path and brings us to a small house surrounded by unruly hedges and several elaborate and rundown birdhouses: an odd agglomeration of mock-Tudor replicas, raised on wooden poles, of the cottage to which they belong. There is an old wrought-iron gate it is always open, stuck in a wet tussock and then a sturdy aluminium one that gives out onto the marsh. At this time of year you have to open it wide to skirt around the sucking mud by the gatepost.

Here, away from the trees, flat land extends in most directions. A hawk passes overhead, too small to be a buzzard, its wings too wide for a sparrowhawk. Peregrine? Hobby? It has gone before we decide. To the right, that is to the east, lurk a few dilapidated buildings that are reputed to have belonged to a pottery or tile works; in the grass between there and the ditch lies the rusted ribcage of an obscure item of farm machinery. Before us, the marsh. There are the usual sheep these full size and filthy: a surprise to find them out here at the start of the year and the small concrete-and-brick huts in which we suppose they must sometimes huddle. On my early visits here, I excitedly took these modest structures for remains of the gunpowder works, but the actual ruins are much harder to see against the grass and reeds, the shining lengths and irregular expanses of inland water.