Maps by Larry Harris.

For Grandfather Hubley (18881975) and

my mother, Dorothy (ne Hubley) Cuthbertson (19212015),

proud Nova Scotians

CONTENTS

Guide

I t was a blast heard round the world. News of what happened when two ships collided in the harbour of the historic port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on December 6, 1917, made headlines worldwide. In times of war, accidents happened in busy seaports, and life went on. But this time, things were different.

One of the vessels involved in the collision was the SS Imo, a Norwegian war-relief ship. The other was the SS Mont-Blanc, a rusting French tramp steamer that was loaded to the gunwales with high explosivesalmost 3,000 tons of picric acid, TNT, and gun cottonwhile piled high on her deck were hundreds of barrels of high-octane benzol fuel. The Mont-Blanc was a floating bomb. As one veteran Royal Navy officer would later marvel, Im surprised the people on the ship didnt leave in a body when they saw the nature of the cargo she had been ordered to carry.

The chain of events that put the Imo and the Mont-Blanc on a collision course was as improbable as it was bizarre. It defied logic. The weather was clear and mild. The sea was calm. Veteran harbour pilots were guiding each ship. The two captains involved were experienced mariners.

Those eyewitnesses who lived to tell the tale reported that they had seen trouble coming long before it ever happened. It was as if events on the water were happening in slow motion. That clich is a clich for a reason.

In the moments after the crash, it appeared as if no great damage had occurred. Then, as the ships were disengaging, the grinding of metal on metal sparked a small fire aboard the French ship. The wispy flames that began to flicker and dance on the Mont-Blancs foredeck quickly took on a life of their own. They became a raging, angry inferno.

Few people in Halifax on this sleepy, sunlit Thursday morning knew the awful secret that the Mont-Blancthe stricken ship that was on fire and drifting toward the Halifax shorelinewas carrying munitions. The curious flocked to the waters edge to watch the excitement as the Mont-Blanc burned. For twenty minutes, spectators stood spellbound. A succession of small explosions, the pyrotechnics soundtrack, echoed across the harbour, drawing collective gasps from awed onlookers. The show was something to behold. But then... in a nanosecond, the show ended, as the unexpected, the unthinkable, happened.

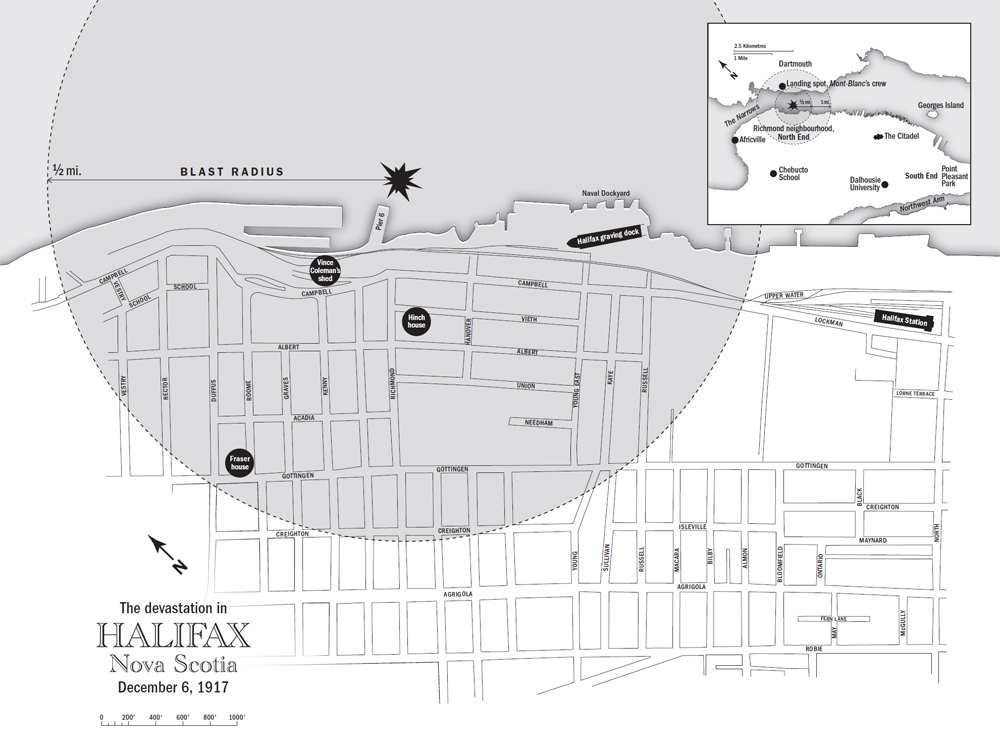

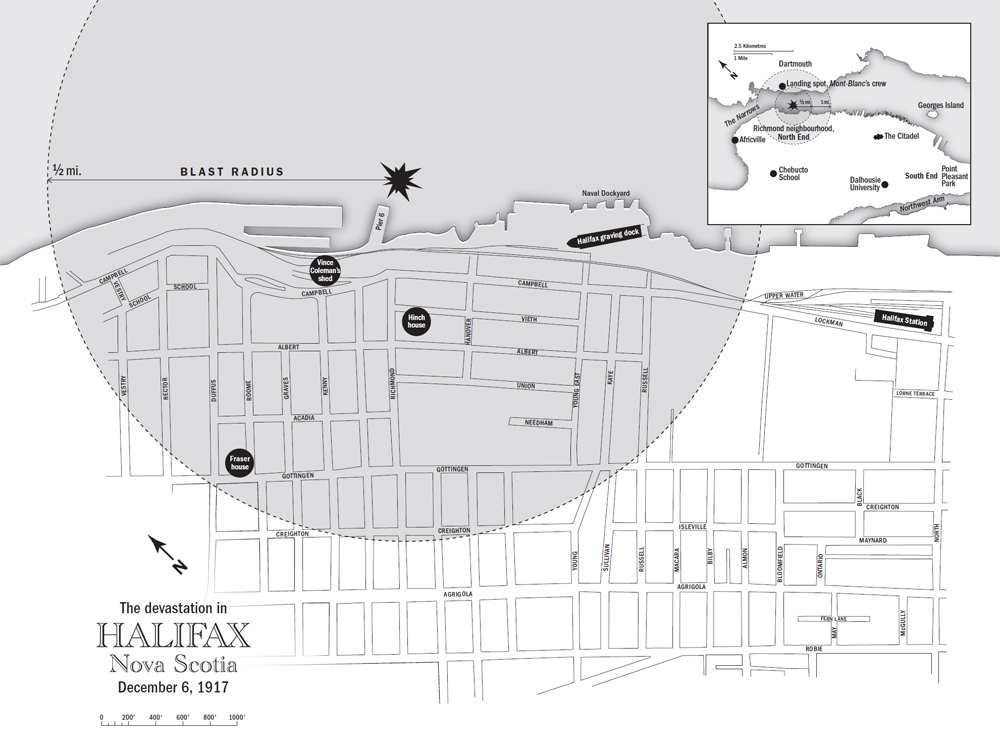

At 9:04 a.m., there erupted an apocalyptic blast the likes of which had never before been seen or heard. The biggest man-made explosion prior to the 1945 atomic bomb blasts unleashed an incendiary firestorm. A split second later, there followed a deadly shock wave and then a killer tsunami. The destructive energy that radiated outward from the blast would claim 2,000 lives. It would also injure 9,000 people, level half the city of Halifax, and shatter windows for miles around. Those who heard the thunderous rumble from afar described it as being a sound for God to make, not man.

So great was the devastation around ground zeroon the water beside Pier 6 in Halifax harbourthat a quarter century later, physicist Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, reportedly studied aspects of the explosion in hopes of gaining understanding of the destructive power of such a huge blast at ground level.

The Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe mused in his play Doctor Faustus, Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscribed. There is no more vivid example of the truth of those words than the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917. The story of the disaster has become an integral element of the citys self-identity and of Canadas national mythology.

The explosion that devastated Halifax on December 6, 1917, is one of the few Canadian historical events that the worldand, indeed, Canadians themselvesremember. The disaster is unforgettable for many reasons, not the least of which is that it was so quintessentially Canadian.

It was a forty-three-year-old family man who emerged as one of the iconic figures involved in the disaster. Vincent (Vince) Coleman, a railway telegraph operator, ignored his own safety when he stayed at his desk to telegraph a Morse code messagea warning to an approaching passenger train. Hold up the train, Coleman tapped out. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys. Colemans heroism may have saved hundreds of lives, but it cost him his own.

Vince Coleman was depicted as the central figure in a 1991 Halifax explosion segment of the popular Heritage Minute series, the historical infomercials produced by Historica Canada (available for viewing online at www.historicacanada.ca). A 2012 survey done by the Ipsos Reid polling firm identified that mini-drama as being one of the most memorable of the eighty-three Heritage Minutes aired to that time. The well-known Montreal businessman and philanthropist Charles Bronfman, who provided money to help produce the series, has a theory as to why. Bronfman has hailed Coleman as the Canadian paradigm of a hero. He was an ordinary guy, who when extraordinary circumstances came along, did the thing he was supposed to do. Thats what [Canadians] are about.

In many regards, that is the essence of the story of the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917. The people of that historic port cityordinary, hard-working men and womensuffered a staggering, catastrophic blow. Yet, incredibly, life in Halifax began to resume within days of the disaster. As one elderly explosion survivor observed many years later, the people of Halifax, like all Canadians, are made from pretty strong stuff.

Over the years, countless articles, stories, and booksboth fictional and non-fictionalhave chronicled aspects of the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917 and its tragic aftermath. There is even a play about the disaster, as well as a 2003 television miniseries called Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion, and, of course, that memorable Heritage Minute.

As Canada and the world mark the centenary of the tragedy, this book offers a fresh look at the remarkable story of Canadas worst-ever disaster. Here are the untold backstories of some key figures who were involved as well as answers to some of the questions that have always lingered.

Was the disaster the result of negligence on the part of the ships pilots, the captains, or the naval officials who were in charge of the port of Halifax? Was the collision of the Imo and the Mont-Blanc the inevitable result of shortcomings in harbour practices and protocols? Or was the blastas many people at the time believedthe result of wartime sabotage carried out by German agents?

A superstitious person well might wonder if the great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917 was the capper in a quartet of epic North Atlantic maritime disasters that shocked the world in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

On April 15, 1912, the unsinkable Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Titanic, the pride of Great Britains White Star Line, took 1,517 passengers and crew to a watery grave after hitting an iceberg off Newfoundland.

Two years later, on the morning of May 29, 1914, the RMS Empress of Ireland ocean liner carried 1,012 victims with her when she went to the bottom of the St. Lawrence River after colliding with a Norwegian collier.