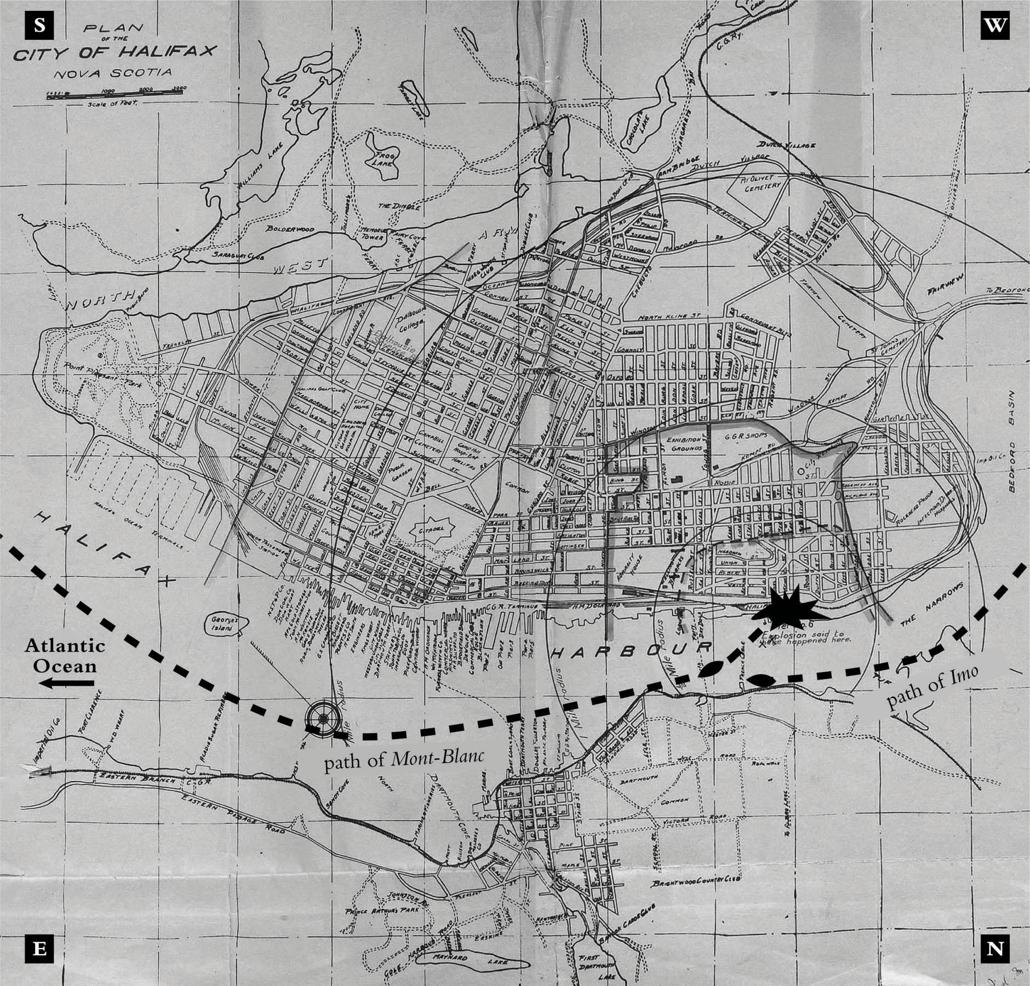

This map was produced by the Royal Society of Canada as part of their detailed scientific report on the Halifax Explosion. Mont-Blanc sailed toward the Narrows, while Imo traveled in the opposite direction, veering toward the left (port) side. When the ships collided, Mont-Blancs crew abandoned ship, and the smoking vessel drifted west into Pier 6, where it exploded. Note: the maps orientation is such that the bottom-right corner points north. (Royal Society of Canada)

To the memory of Wally and Helen Graham,

my beloved Canadian grandparents,

who first told me this remarkable story,

and the good people of Halifax

O n Thursday, December 1, 2016, the people of Boston slogged through a drizzly day with temperatures in the 40s neither fall nor winter, the kind of cold that gets deep in your bones and stays there.

At 8:00 p.m., 15,000 hearty souls left their warm, dry offices and homes to crowd around the stage in the center of Boston Common, the nations oldest city park, dating back to 1634. They were waiting for the mayor of Boston, the premier of Nova Scotia, the Canadian Mounted Police, and Santa Claus himself to turn on the 15,000 lights draped on a forty-seven-foot white spruce Christmas tree, a perfect specimen, and brighten the dark, foggy gloom. When the crowd finished counting down, the people backstage flipped the switch and set off fireworks, and the crowd cheered as though relief had been delivered.

Every year the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources sends scouts across the province to locate the best tree. They found the 2016 winner in Sydney, Nova Scotia, but it was unusual because it came from public lands, instead of being donated by private citizens who compete for the honor of having their tree selected. After a tree-cutting ceremony, they load it onto a big flatbed truck, strap it down, and ship it to Halifax for a send-off parade. There they pin a provincial flag on both sides so fellow travelers along the three-day, 660-mile journey to Boston know where it came from. The tree even comes with a band of dignitaries, including an official town crier and its own Facebook fan page, and twitter account, @TreeforBoston.

All this costs the citizens of Halifax about $180,000 to continue a tradition that started in 1918and they do it enthusiastically. As one Nova Scotian said, Why do we have to stop saying Thank you!?

What did Bostons ancestors do to inspire contemporary Haligonians to keep thanking them a century later?

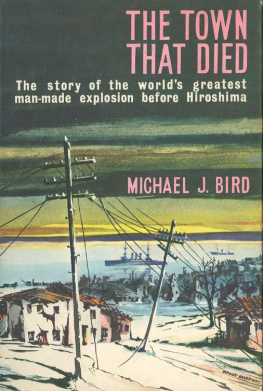

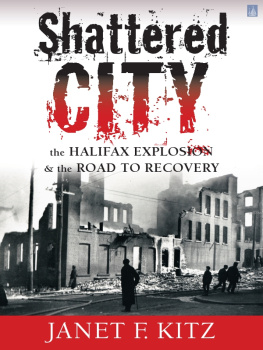

The answer to that question harkens back to World War I, which introduced submarines, tanks, and airplanes; ended empires in Russia, Turkey, Austria, and Germany; and created a new world order. It lies in a forgotten disaster that occurred on Thursday, December 6, 1917, in Halifaxthe most destructive man-made explosion until Hiroshima, one that blew out windows 50 miles away, rendered 25,000 people homeless in an instant, wounded 9,000 more, often horrifically, and killed 2,000, most of them in a flash. It lies in hundreds of Bostonians rushing to help before the people of Halifax even askeda response so overwhelming that it helped transform these two countries from adversaries to allies.

Ultimately, it lies in a split second that brought out the best of both nations.

O n November 9, 1917, with the Great War building to its horrendous crescendo, the French freighter Mont-Blanc docked at Gravesend Bay in Brooklyn, New York. Although the United States had joined the Allied forces a few months before, American troops were only just starting to fill the trenches of France, while Vladimir Lenins Bolshevik Revolution had toppled the Russian government two days earlier. The next day Lenin had promised his countrymen they would soon be dropping out of the most destructive war the world had ever seen. This presented Germany with its best chance to break the grueling three-year standoff on the Western Front, and it was therefore of paramount importance that the Allied powers send munitions and men in greater numbers than ever before to prevent the Germans from breaking through.

The United States had remained neutral until Apri l 6, 1917, but American manufacturers, shipping companies, and ports had been doing brisk business since the war broke out in 1914, selling the British, French, and other Allied powers supplies, weapons, and explosives. Tons of exports poured out every day from Gravesend Bay, squeezed in between Bensonhurst and Coney Island.

Mont-Blanc, built in 1899, was not among the most impressive vessels crossing the sea. She measured 320 feet long and 47 feet wide, fairly standard for a transatlantic vessel, and she wasnt the oldest ship on the seas, but her best days were definitely behind her. She was slow, with a top speed of about 12 miles per hourroughly one-third the speed of Lusitaniawith a long history of bare-minimum maintenance. Sensing opportunity when the war started, the French Line bought her in 1915, fixed her up enough to transport supplies from North America to Europe, and turned her into a moneymaker.

But she would be asked to do more. In 1917, German U-boats had been sinking military and merchant ships by the hundreds each month, forcing the Allied Powers to use any ships still afloat on increasingly dangerous missions.

The previous month, the French Line put Mont-Blanc in the hands of Captain Aim Joseph Marie Le Mdec, thirty-eight. At five foot three and 125 pounds, Le Mdec was not physically imposing, but he knew how to carry himself like a captain, an impression buttressed by his regal bearing and carefully groomed jet-black beard. His highly disciplined, by the book approach was not initially well received by his thirty-six-man crew and four officers on their first transatlantic journey, but by the time they reached New York, he had earned their respect and trust.

When Mont-Blanc pulled into Gravesend Bay, Le Mdec and his crew had no idea what cargo they might be picking up. During the Great War it could be almost anything, and the premium on security precluded advance notice. But they started getting hints before the cargo could be loaded onto the creaky Mont-Blanc. Shipwrights at Gravesend Bay attached custom-made wooden linings and magazines to the inside of the steel hull to keep the cargo as tightly packed, hermetically sealed, and immobile as possible, because high explosives are so sensitive that a good jolt can set them off. The shipwrights worked around the clock for two days to secure the partitions with copper nails because copper doesnt spark when struck. They were told a single spark could send them all skyward.

Finally, on November 25, 1917, the stevedores started loading the cargo under the protection of local police surrounding the ship. The stevedores so feared accidentally blowing up the volatile cargoand the ship, the docks, and themselves with itthat they fastened canvas covers over their boots to keep their soles from sparking against the steel deck.

When a French government agent finally told Captain Le Mdec what they were loading on his ship, it was a most unpleasant surprise: Mont-Blanc would be carrying almost nothing but high explosives back to Bordeaux, France. Le Mdec normally exuded the calm confidence expected of a captain, but his face belied his alarm. If the U-boats success forced the Allies to squeeze more from their remaining ships, it had the same effect on the Allies captains. Le Mdec had earned a record as a competent helmsman, but hed never captained a ship as big as