Note to the Reader

A MERICANS AND C ANADIANS spell certain words differentlyfor example, color versus colour and harbor versus harbour. Over time, Americans dropped the u when spelling both of these words. In the text, when referring in general to the body of water where this story takes place, I use the American spelling, harbor. But the proper name of that harbor, which is in Canada, is Halifax Harbour. When mentioning it by its full name, I use the Canadian spelling.

The treasuries of Canada and the United States call their paper currency by the same namedollars. However, a Canadian dollar is not usually the exact cash equivalent of a U.S. dollar. In this book, all dollar amounts are given in Canadian dollars unless specified as U.S. dollars. In either case, the currency amounts are as they appear in the documents of the time and are not converted into modern-day equivalents.

As the cities in this story grew, some streets were renamed. In Halifax today, Barrington Street runs along the waterfront for most of the northsouth length of the city. But until the beginning of 1917, the portion of Barrington Street that ran through the Richmond neighborhood, where much of this story occurs, was named Campbell Road. For longtime residents, getting used to the name change wasnt easy. Out of habit, many of the survivors, when talking about their experiences during the explosion and its aftermath, referred to the street by its old name. And of course it was listed as Campbell Road on old maps. To avoid confusion, I have used Barrington Street, its official name by December 1917.

In 1917, the Mikmaq (pronounced Mee-gamok and often spelled as Micmac in historical documents) settlement in the Halifax area was in a district of Dartmouth called Turtle Grove, which is located just south of an area called Tufts Cove. Depending on the source, the settlement is called either the Tufts Cove Mikmaq settlement or the Turtle Grove Mikmaq settlement. After canvassing many people and receiving mixed answers, I have chosen to use Tufts Cove. This is the name that Jeremiah (Jerry) Lonecloud, one of the elders who lived in the Mikmaq settlement, used in his letters written in 1917 to the Department of Indian Affairs.

In keeping with long-established seafaring tradition, I refer to a ship as she or her.

Its against our nature not to know about times past.

We need stories. We need stories the way we need bread or water.

D AVID M C C ULLOUGH,

AUTHOR AND HISTORIAN

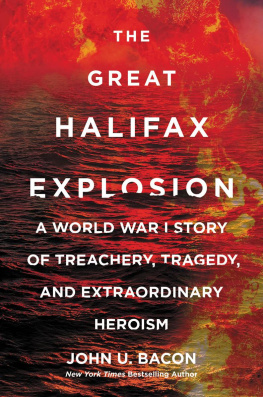

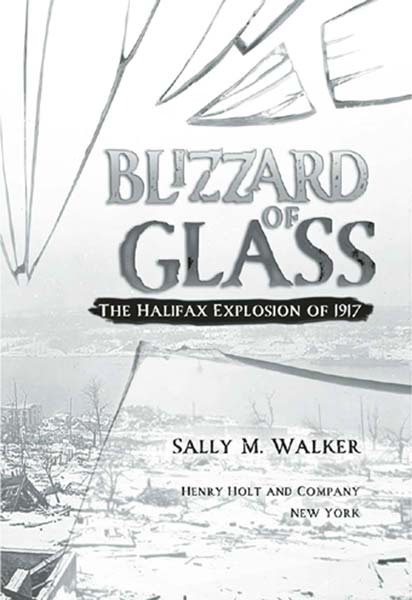

A Story to Tell

The hands of this clock always remain at 9:05, a silent remembrance of a terrible tragedy.

[Sally M. Walker]

H ALIFAX, THE LARGEST CITY OF Nova Scotia, Canada, has a story to tell. Fourteen bells in a memorial tower ring part of the tale. In the city hall clock tower, the locked-in-place hands on the clock that faces north freeze a moment of the story, left as it was on that long-ago day. A museum containing grim reminders and libraries filled with age-old pages share more. The people of Halifax add chapters to the story each time they speak the memories of those who livedand diedat that time. Old scars are hidden by sturdy stone houses, and tall trees line remade streets. But the roots of the story are still there, and they grow deep.

Located on a small peninsula surrounded by salty water, Halifax is rich with history. People have lived in the area for ten thousand years. Since time out of mind, the settlements and campsites of the Mikmaq, members of Canadas First Nations people, have dotted the landscape. Generation after generation, men and boys hunted in the evergreen forests; they fished in the lakes and flowing rivers. Women and girls built sturdy birch-bark-covered wigwams and gathered plants for food and medicinal use. They stitched clothing and made baskets decorated with elaborate patterns of interwoven porcupine quills. For hundreds of years, the Mikmaq found the rocky shore along Halifaxs large, hourglass-shaped harbor a perfect place to live.

One of the birch-bark-covered dwellings in the Mikmaq settlement at Tufts Cove in about 1900.

[Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management]

In the early 1600s, French explorers reached the shores of Nova Scotia and called the land Acadia. The Mikmaq allowed them to establish settlements where fishers dried their catches before shipping them to Europe. By the 1620s, Scottish settlers had made their way to the land, calling it Nova Scotia, which means New Scotland in Latin. For the next century, Great Britain and France played tug-of-war over Nova Scotia. Great Britain was the eventual victor.

In 1749, under the leadership of Edward Cornwallis, ships carrying more than 2,500 British settlers arrived and established a town they named Halifax. It became the capital of Nova Scotia, the leading port city for eastern Canada, and the site of a naval base. The Mikmaq, still living on most of their traditional lands, signed peace treaties with the British. In the late 1700s, an earthen fort named Fort Needham was constructed on the top of a 220-foot hill that overlooked the dockyards along the northern end of the city. In 1828, a stone fort called the Citadel was built on an even higher hill nearby. And all around the two hills, people built homes, schools, and businesses. Merchant ships sailed in and out of Halifax Harbour. By the 1860s, trains chugged into the city. Together, the railroad and ships created a transportation network that carried timber and fish and other trade goods to places around the world. And so Halifax grew.