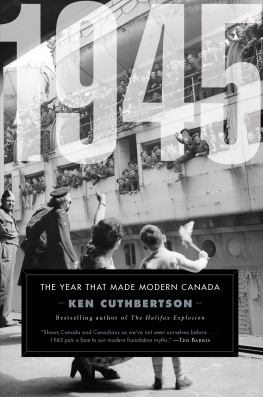

The 8,000 soldiers who arrived in Halifax aboard the SS le de France on June 21, 1945, were the first Canadians to be repatriated from Europe at wars end. (Library and Archives Canada [LAC], no. PA-192969)

Contents

Im thinking hard about the future. [Canada] may be The Country.

Benjamin Britten, English composer, 1939

T HERE HAS NEVER BEEN ANOTHER YEAR LIKE IT, AND IT SEEMS unlikely there ever will be again. Not for the world or for Canada. The year 1945 was a watershed in the life of this country. Oral historian Barry Broadfoot said it succinctly and well when he observed that at wars end there was very little in Canada that was as it had been in [September] 39.

Not only did 1945 mark the end of the catastrophic six-year global war that had scarred and forever changed Canada, it was also the momentfor thats what a year is in the grand sweep of historythat the light bulb went on. Suddenly, it all made sense.

It was in 1945 that Canadians began trying to sort out who they were as a people and decide where their home and native land was or should be headed in the post-war era. Nineteen forty-five was the year when most Canadians began to learn that, for the first time, most of them could live comfortably.

The potential for prosperity and greatness had been there from the beginning in 1867. It beckoned, as alluring as a wondrous unopened gift. In 1904, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier asserted that the twentieth century belongs to Canada. Others recognized the same potential; the American corporate titan Thomas Watson Sr. was among them. The chairman and chief executive officer of the mighty International Business Machines (IBM), one of the worlds most successful corporations, recognized Canadas potential, and he said as much.

In November 1938, Canada remained in the grips of the Great Depression, and yet where so many others saw only despair, Americas $1,000-a-day manas the media dubbed the sixty-four-year-old Watson in the days when $1,000 was still a lot of moneysaw no end of economic potential and opportunities. On a visit to Toronto, Watson advised R.E. Knowles, the Toronto Daily Stars ace celebrity reporter (and author of the book Famous People Who Have Met Me), that he was bullish on Canadas economic prospects. Said Watson, I think this [of the] future: your country is eligible, in the next twenty-five years, for just about the greatest expansion of any country in the world. The reasons were obvious to him: Canadas vast area... her illimitable resources, and the high average of her citizenship.

Watson, who brimmed with Yankee-trader business smarts and a bustling can-do approach to life, recognized what too many Canadians in their characteristic reserve either overlooked or were too timid to seize upon and run with. The Canada of the 1930s was a vast, undeveloped land populated by just 11.5 million residents. Where others saw this as being problematic, Watson saw opportunity writ largeCanada was a blank canvas with unlimited development potential. As it turned out, the IBM chiefs instincts were razor sharp. However, he was a tad off in his timing; his prediction came true a lot sooner than he or anyone else ever dreamed.

That happened not because of the foresight of business entrepreneurs. Nor was it thanks to the kind of government-backed jumpstart that helped the United States escape the ravages of the Great Depression; Canada had no President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and it had no New Deal. It was the September 1939 outbreak of war in Europe that was the catalyst.

At the time, the Dominion of Canada had a mere seventy-one years of history in its rear-view mirror. It was still a youngster as nations go. Incredibly, there were Canadians who were as old as the country itself; some of them had vivid memories of that July day in 1867 when Canada won its independence from Britain.

The British influence was still very strong and pervasive in Canada during the WWII era. (LAC, PA-1930077)

Toronto barrister James Roaf, who was eighty-eight years old in 1939, boasted to a newspaper interviewer that he had many tales to tell of families of the Fathers of Confederation, many of whom he knew personally. In a conversation with that same journalist, businessman Alexander Galt recalled that his father, Sir Alexander T. Galtone of the thirty-six Fathers of Confederationwas the soul of generosity and kindness. He never whipped me once. Those were very different times.

Had Roaf or Galt been asked, they doubtless also could have recounted how Canada had always been a sleepy economic and political backwater. The national economy was resource-driven, export-dependent, and cyclical. Canadians enjoyed good times, and they suffered through bad times. None were leaner or meaner than the decade of the 1930s. The protectionism that was rampant globally during the Great Depression stifled markets for the natural resources and agricultural produce that were the lifeblood of the Canadian economy. And so, no country suffered more in the 1930s.

Germany was the poster child for economic despair in those years, but consider this: while that nations gross national product (GNP) fell by sixteen per cent from 1929 to 1933, Canadas GNP plummeted by almost fifty per centfrom $6.1 billion to $3.5. An economic powerhouse Canada was not.

The nadir of the downturn came in 1933. That year, half of this countrys wage earners were drawing some form of government assistance. The national unemployment rate soared to thirty per cent, and the average annual income was less than $500 at a time when the poverty line for a family of four was more than double that amount. Small wonder that hope and optimism, two of lifes essentials, were in such short supply. Times were tough. Not Honey, were-a-little-short-for-a-Caribbean-cruise tough, but rather Theres no-money-for-food-or-rent-this-month tough.

Conditions had improved marginally as the decade wound down; however, by 1939 the world was on the slippery slope to the bloodiest, most costly war in the long history of bloody, costly wars. Sixty million peoplea number so obscenely large that it boggles the mindwould die in the conflict. Yet Canada was fortunate. Geographically insulated from the carnage and generously endowed with natural resources, this country was one of the precious few that benefited from the conflict. The notion that war is good for the economy is a clich for a reason. Its often true.

Canadas GNP leapt from $5.6 billion in 1939 to $11.9 billion in 1945. If the nations economic possibilities suddenly seemed endless, its because they were, and people realized it. By 1945, this country was wealthier, more robust, and more outward-looking than anyone had ever imagined at the onset of World War II (WWII) six years earlier. Today, Canadas GDP is more than $1.7 trillion, and this country is one of the most prosperous on the planet.

The changes that transformed Canada during the war happened at warp speed. In retrospect, its stunning to realize how many game-changing developments coalesced in 1945 and catapulted this country into the post-war era on a giddy, gloriously prosperous high that would endure for decades. As a year-end editorial in the