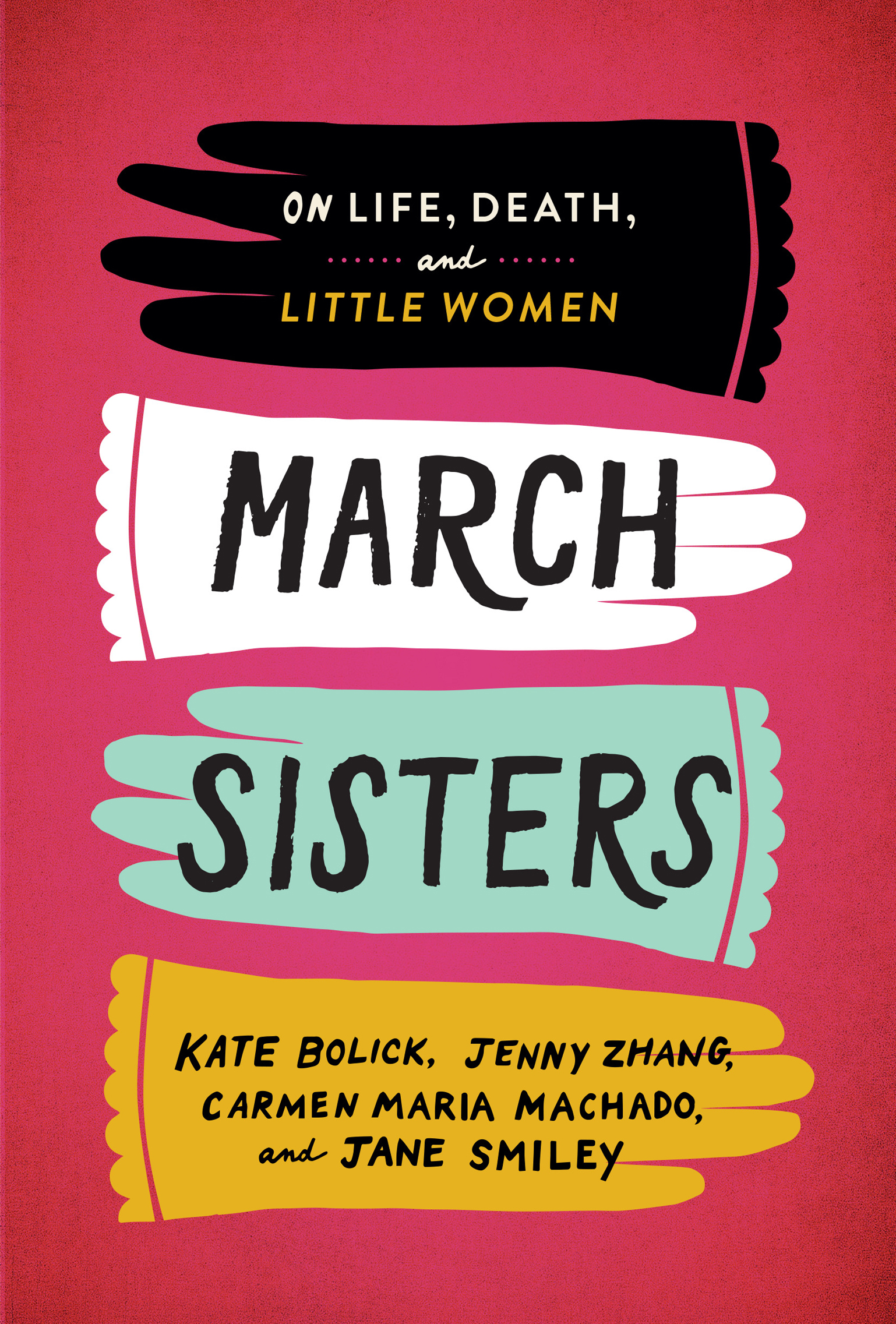

MARCH SISTERS: ON LIFE, DEATH, AND LITTLE WOMEN

Volume compilation copyright 2019 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Megs Frock Shock, by Kate Bolick.

Copyright 2019 by Kate Bolick.

Does Genius Burn, Jo? by Jenny Zhang.

Copyright 2019 by Jenny Zhang.

A Dear and Nothing Else, by Carmen Maria Machado.

Copyright 2019 by Carmen Maria Machado.

I Am Your Prudent Amy by Jane Smiley.

Copyright 2019 by Jane Smiley.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher,

is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print,

authoritative editions of Americas best and most

significant writing. Each year the Library adds new

volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas

foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about

Library of America, and to sign up to receive our

occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with

Library of America authors and editors, and our popular

Story of the Week e-mails.

eISBN 9781598536294

A S J ANE S MILEY notes in the pages of this book, we tend to think and speak of Louisa May Alcotts Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy as if they were real. Readers have had an intense interest in the stories of the four March sisters from the beginning. After the publication of part one of Little Women in 1868 (part two followed in 1869), Alcott was inundated with letters, many of them addressed to Jo, demanding to know what happened to the four sisters. Girls write to ask who the little women marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a womans life, Alcott wrote in her diary. I wont marry Jo to Laurie to please any one. Readers would continue to send fan letters to Alcotts publisher until at least 1933, forty-five years after her death. In the decades after the novels release, Little Women clubs became common across the country, with members taking on the identities of the March sisters, just as Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy took on the identities of the Pickwick Society members in the novel. More recently, Little Women has served as inspiration to screenwriters, directors, and actors in more than a dozen film and television adaptations. Ursula K. Le Guin, Patti Smith, Susan Sontag, and J. K. Rowling, among numerous others, have claimed Little Women as an influence. Many more future novelists and feminists will be emboldened by Jos example, while others will continue to find encouragement in Megs egalitarian marriage, Beths self-sacrifice and love of family, and Amys relentless pursuit of art and beauty.

Often first encountered in early adolescence, Little Women is one of those childhood favorites readers return to in later years, for its pleasures are many and changeable, and its life lessons about love, loss, patience, duty, hard work, and of course marriage are always worth hearing (especially if one has forgotten them). Rereading Little Women in adulthood, we may appreciate complexities previously undetected, or we may, with the shock of recognition, come to understand something about our own childhoodand hence about ourselves. But Little Women remains primarily a book for young readers, and for girls especially. Alcott was blunt about her aims in writing about four sisters growing up in a small New England townshe once famously (and perhaps dismissively) called her work moral pap for the young. But to say that Little Women was written to both delight and instruct is only to say it is a book like George Eliots Middlemarch (187172) or John Bunyans spiritual allegory The Pilgrims Progress (1678, 1684), whose salubrious example is often invoked by the March parents. It is the kind of book in which readers find themselves.

Alcott knew how good a book she had written. It reads better than I expected, she confessed in her journal in 1868. Not a bit sensational, but simple and true, for we really lived most of it, and if it succeeds that will be the reason of it. This biographical dimension of the novel has undoubtedly increased our interest in the Marches, even as it has obscured their real-life antecedents (the Orchard House museum advertises itself as the home in which Alcott set Little Women). Tomboyish Jo was based on Alcott herself, known as Lou or Louie in the family. Like her hot-tempered counterpart, Bronson and Abba Alcotts second daughter had a mood pillow and helped to support her family by writing thrillers. Unlike Jo, she would never marry. Meg was based on Alcotts older sister Anna, who like Meg worked as a teacher but did not enjoy it. Unlike Meg, Anna went on from childhood theatricals to become an actress, performing in an amateur theater in Walpole, New Hampshire, and meeting John Pratt, the original of John Brooke, when they performed together in Concord. She married Pratt in May 1860, and had two sons, Frederick and John. Beth was based on the third Alcott sister, Lizzie. Like Beth, she was the shyest sister, nicknamed Little Tranquility. Lizzie loved to play the piano (she was given one by a wealthy benefactor), and left school at fifteen to stay home and help keep house. When in spring 1856 she and younger sister May both contracted scarlet fever, Lizzie never fully recovered. She died at age twenty-two. And Amy was based on May, who acknowledged as much in a letter she wrote to her friend Alfred Whitman (one of the sources for Laurie) after the book was published: Did you recognize... that horrid stupid Amy as something like me even to putting a cloths pin on her nose?... I used to be so ambitious, & think wealth brought everything. Like Amy, May was the pet of the family and longed to become a famous artist; a family friend paid her way to study in Boston with William Morris Hunt. She was able to study in Europe only after the success of Little Women allowed Louisa to send her. During Mays lifetime, her work was exhibited twice at the Paris Salon.

Four self-described fans of Little WomenKate Bolick, Jenny Zhang, Carmen Maria Machado, and Jane Smileytalk in this book about their personal connection to the novel and what it has meant to them (as children, adults, or both). More particularly, each of the writers takes in turn one of the March sisters as her subject. Kate Bolick finds parallels in the chapter about Meg attending the Moffats ball to her own relationshipor resonancewith clothes. Jenny Zhang, when she first read Little Women as a girl, liked Jo least of the March sisters because Jo reflected Zhangs own quest for genius, which she feared was too unfeminine. Carmen Maria Machado writes about the real-life tragedy of Lizzie Alcott, and the horror story that can result from not being the author of your own lifes narrative. And Jane Smiley rehabilitates the reputation of Amy, whom she sees as a modern feminist role model for those of us who are, well, not like the fiery Jo. Taken together, these pieces are a testament to the ways in which