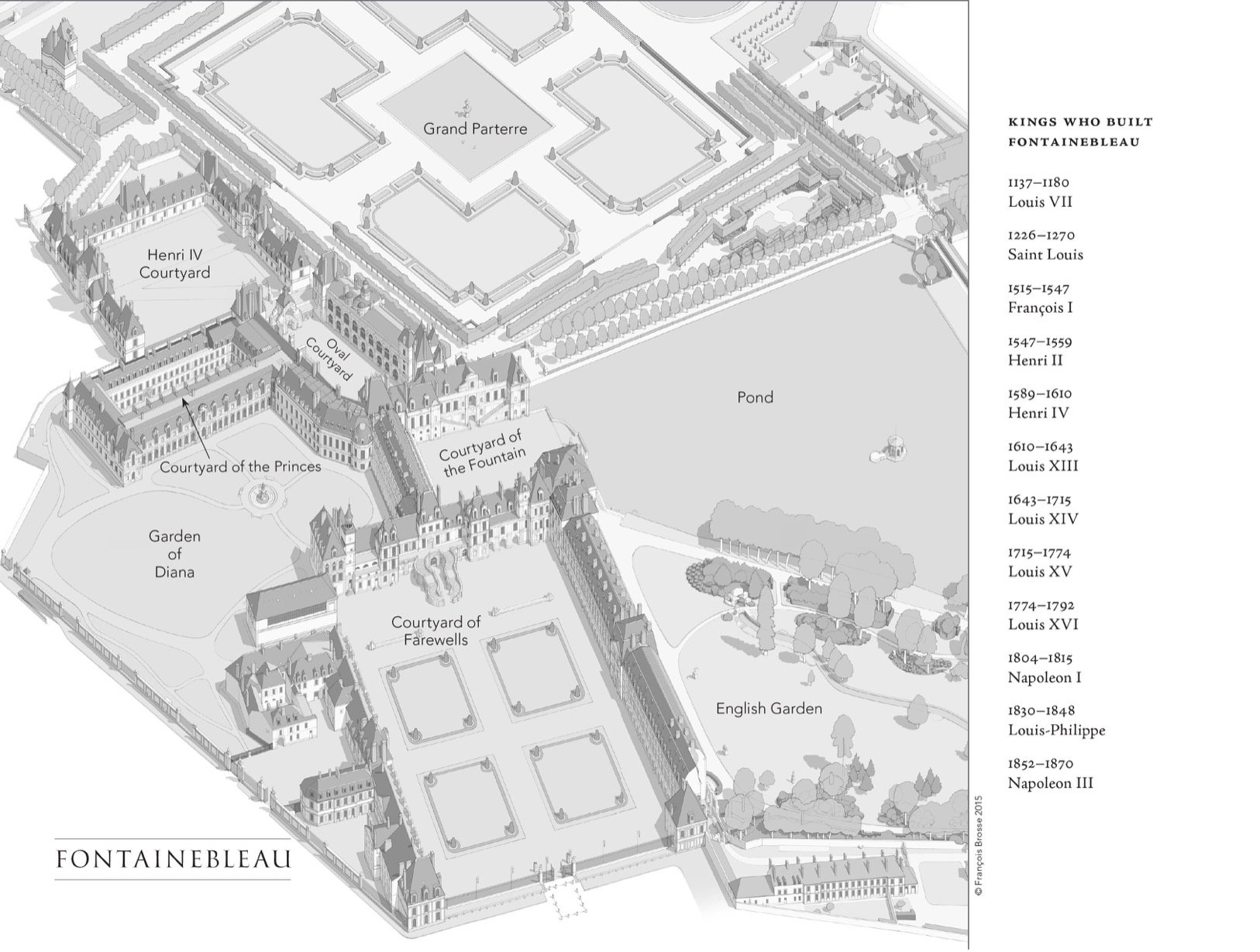

Visit http://bit.ly/1T9R5UQ for a larger version of this image.

A LSO BY T HAD C ARHART

Across the Endless River

The Piano Shop on the Left Bank

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2016

Published in Penguin Books 2017

Copyright 2016 by Thad Carhart

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Frontispiece: Francois Brosse, 2015

ISBN 9780143109280 (pbk.)

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Carhart, Thaddeus.

Title: Finding Fontainebleau : an American boy in France / Thad Carhart.

Description: New York, New York : Viking, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016008395 (print) | LCCN 2016009173 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525428800 (hardback) | ISBN 9780698191617 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Carhart, ThaddeusChildhood and youth. | AmericansFranceFontainebleauBiography. | BoysFranceFontainebleauBiography. | Fontainebleau (France) Biography. | Fontainebleau (France) Social life and customs20th century. | Chteau de Fontainebleau (Fontainebleau, France) | Fontainebleau (France) Buildings, structures, etc. | Carhart, ThaddeusTravelFrance. | FranceDescription and travel. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | TRAVEL / Europe / France. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / General.

Classification: LCC DC801.F67 C37 2016 (print) | LCC DC801.F67 (ebook) | DDC 944/.36082092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016008395

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Cover design: Colin Webber

Cover images: (inset) courtesy of the author; (Fontainebleau Palace) Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company, LC-DIG-PPMSC-05036

Version_2

To the memory of my parents,

May and Tom Carhart

CONTENTS

Visit http://bit.ly/1SyA22U for a larger version of this image.

CHAPTER 1

FLIGHT

A ll these years later I can recall with keen precision the moment when the bottom dropped out, because that is exactly what it felt like: one moment we were flying, shaking a bit from turbulence, the next we were falling, in a calm, eerie quiet broken only by the sound of the four engines laboring uselessly. Then the air caught us again and it was bad: the plane pitched violently up and down, from side to side, every way imaginable. The passengers found their voice then, after the expectant dread of the free fall. This was active, maniacal horror, and people screamed. It was the first time I saw an adultmany of them, in factexpressing fear without reserve. The woman across from us started to cry and yell, and there was nothing to be done but listen and watch with a kind of terrified fascination.

The other unforgettable occurrence was the almost simultaneous eruption of airsickness among the passengers. On a modern airliner, when you find one of those little airsickness bags in the seat pocket, youre looking at a quaint reminder of what was not so long ago a dire necessity. The bags used to be much bigger, there were several per seat, and people used them. When the serious shaking began, my mother managed to open a bag for my baby sister and give another to my brother Tom, known for his sensitive stomach. The rest of us were fine for a while, lurching against our seat belts as we heard the occasional crash of plates or glassware from what was then still called the galley. Gradually, however, the smell overcame everythingnot everyone had fished out a bag in timeand made me hopelessly, convulsively sick. This went on for what seemed like an eternity. The shrieks and yells of initial panic subsided into a generalized moaning punctuated by the occasional sob or an unproductive retching. Stomachs were by now empty and the planes shaking went on: all you could do was wait.

My mother was a nurse who had dealt with her share of traumas and emergencies, and she had no particular fear of flying, but years later she admitted that the flight from Labrador to Ireland had been one of the most searing experiences she could recall. Planes very rarely go down because of weather, my father had reassured her many times, and so she waited it out with the five children, awareif not exactly acceptingthat our lives lay in the hands of the pilots and in the airworthiness of what was reputed to be a very sturdy troop carrier.

We landed at Shannon at dawn, and the sense of salvation was absolute. One woman had become loudly agitated about an hour before we descended, as we plunged into yet another bout of turbulence. Let me out of here! I have to get out of here now! she wailed, but one of the crew members hastened to the back and somehow calmed her hysteria. For all I know she still lives in Ireland, though it seems more likely that she made her way back to America by ship, there to await the advent of jets to carry her above the weather.

When we staggered down the stairs and breathed the balm of fresh air, we were greeted by a team of workers who looked as if they had been assembled to deal with a chemical spill (which, in a way, they had): overalls, hoods, canvas masks, brushes, and pails. They scoured the insides of the plane while we were being cleaned up in the terminal building as best my mother could manage, telling us repeatedly, as if to convince herself, The worst is over. As she almost always did, my mother was telling us the truth, and I remember my next-oldest brother, Judd, saying that it sounded reasonable since we had indeed survived; short of a crash, he told me, nothing worse than the night we had just lived through could possibly be imagined.

Total uproar had reigned on moving day in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C., when it came time to say good-bye to the family dog, our cocker spaniel Apple, banned from Europe by something called quarantine that my mother explained endlessly and that I never truly understood (Why arent