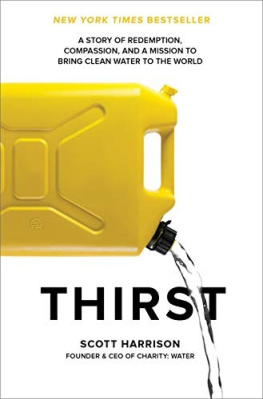

Copyright 2018 by Charity Global, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Currency, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

CURRENCY and its colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

For Jackson and Emma.

I love you both so much, and I cant wait to see who you become.

1

Numb

NEW YORK CITY, FALL 2003

It started in my arms and legs. The nerve endings would go dead for twenty or thirty minutes, like Id woken up on a limb that fell asleep. Sometimes the fingers of my right hand lost sensation, and then a prickly blanket of numbness would spread to my wrist and up my arm. I couldve banged on my hand with a hammer and still felt nothing.

At first I thought there must be a simple explanation, like a pinched nerve. I was twenty-eight years old, with no history of serious illness. But when the episodes became more frequent, I got the name of a neurologist in Manhattan and made an appointment.

Sitting in the dingy waiting room, I nervously flipped through a half-dozen dog-eared magazines, hoping to take in some news from the real world. It was mostly bad. Bombings in Istanbul, suicide attacks in Iraq, the passing of Johnny Cash.

A nurse called me to the reception window and handed me a stack of forms to fill out. Name, age, height, and weight were easyScott Charles Harrison, twenty-eight, six foot one, and a slim 170 pounds, thanks to a steady diet of Marlboro Redsbut the long list of questions about my lifestyle wasnt so simple. Looking through the packet, I realized that I didnt dare answer truthfully, lest the doctors think the presentable college grad in front of them was some kind of degenerate.

Do you smoke cigarettes? (Two to three packs a day. Is that too much?)

Do you consume alcohol? How many drinks per day? (Up to ten drinks, but I try not to mix. My current favorites, in order: Champagne, beer, and vodka and Red Bull.)

Do you use recreational drugs? If so, how frequently? (Well, that really depends on how much Ive had to drink. Cocaine, two to three times a week; Ambien to come down; MDMA whenever I can get my hands on it.)

Anyone who knew the full extent of my partying wouldve said it was no wonder I was finally having health problems. But Id come here for a brain scan and a quick diagnosis, not a lecture. And the fact was, getting wasted every night was my job.

For the last ten years, Id climbed the ranks of New York nightlife to become one of the top club promoters in the city. Most nights, youd find me at the hottest party in town, sitting at the owners table with beautiful women, drinking expensive Champagne (or occasionally spraying it), and looking like the guy who had it all. And for a while, I did.

I was making about $200,000 a year but living like a millionaire, thanks to the perks. The place I called home was a big, industrial Midtown loft with a baby grand piano in the living room, a killer stereo system, and a private rooftop patio. Bacardi and Budweiser each paid me $2,000 a month just to be seen drinking their brands in public. On my wrist, I wore a Rolex Oyster Perpetual, which I loved to flash at club photographers with a knowing smirk. The watch had been a gift from my then-girlfriend, a nineteen-year-old Danish model whose face graced the covers of Vogue and Elle.

I hadnt always lived like this. Ten years earlier, when I moved to the city and began collecting these superficial markers of success, one of my first mentors in nightlife said, Scott, youre too nice. If youre going to do this right, you need to be seen out every night, spending money, with a hot model on your arm.

Mission accomplished. But somewhere along the way, the sameness of nightlifebooze, drugs, girls, repeatmade me restless. I wanted change, and the more things stayed the same, the more booze, drugs, and girls Id needed to force my mind and body to show up for work with a smile. Its like what Ernest Hemingway said about going bankrupt: It happened gradually, then suddenly. For me, suddenly would involve a gun, a bottle of Scotch, and a cobalt-blue Mustang. But that comes later.

Over several weeks in the fall of 2003, I endured a battery of medical tests, searching for the cause of my numbness. Technicians examined my brain and spinal cord with an MRI and a CT scan, looking for possible culprits: tumors, blood clots, bone and tissue irregularities. Doctors put sensors on my arms and legs, monitoring the electrical activity from my brain to my muscles and nerves. Nurses stuck me with needles, drew blood, and ordered me to urinate in small plastic cups.

But in the end, all my tests came back normal. They couldnt find anything wrong with me. I was simply going numb.

Maybe its the cigarettes? I said to my business partner, Brantly Martin, as I fumbled to open my third pack of Reds for the day. We were on our way to a club.

Why dont you try to cut down to two packs and chill on the booze? he offered.

We joked about it, but inside, I was gripped with a quiet certainty that I was dying of some terrible disease that the doctors and their tests had missed. I used to find humor in darkness. I even laughed in the face of death once. It was a few years back. I was high on ecstasy and trying to get a friends attention, and I crashed my hands through the floor-to-ceiling windows of a building at New York University. The pane shattered into pieces, and shards of glass rained down, making cuts all over my face and hands. I bled all over the backseat of the cab on my way to the ER, but I couldnt stop laughing about it. I didnt care. At twenty-five, you think youre going to live forever. Until one day, you dont.

Alone in my loft later that night, I typed numbness into Google, trying to self-diagnose my condition. Trying to find a solution that the doctors couldnt. There, high in the results, among the generic medical advice, I was surprised to see a religious essay. I clicked the link and got lost in a sermon about spiritual numbness, about how ones conscience can become seared to the point where it no longer works. Near the end of the sermon, the author asked, Are you right with God?

As a child, Id heard that question a hundred times from the pulpit, but now it filled me with existential terror. I wondered what would happen if I actually died. Would a childhood full of fervent bedtime prayers, Bible study, and church band still count? I wasnt so sure. I turned off my computer and climbed into bed, my right arm still tingling like a pincushion being poked by a thousand needles.

My fathers worried voice filled my head. Please pray for our son. Hes gone prodigal, Dad would tell his friends at church.

It was true. When I left home at nineteen, Id turned my back on faith, virtue, and just about everything else that mattered most to Chuck and Joan Harrison. I still called my parents every few weeks, though. Mom would always ask about my spiritual life. Dad would ask how the nightlife business was going, and then hed pass along words of wisdom from the Bible, trying to reignite my interest in faith. Uh-