Portfolio / Penguin

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Water.org

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Image credits: photographs by Todd Williamson for Water.org, .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

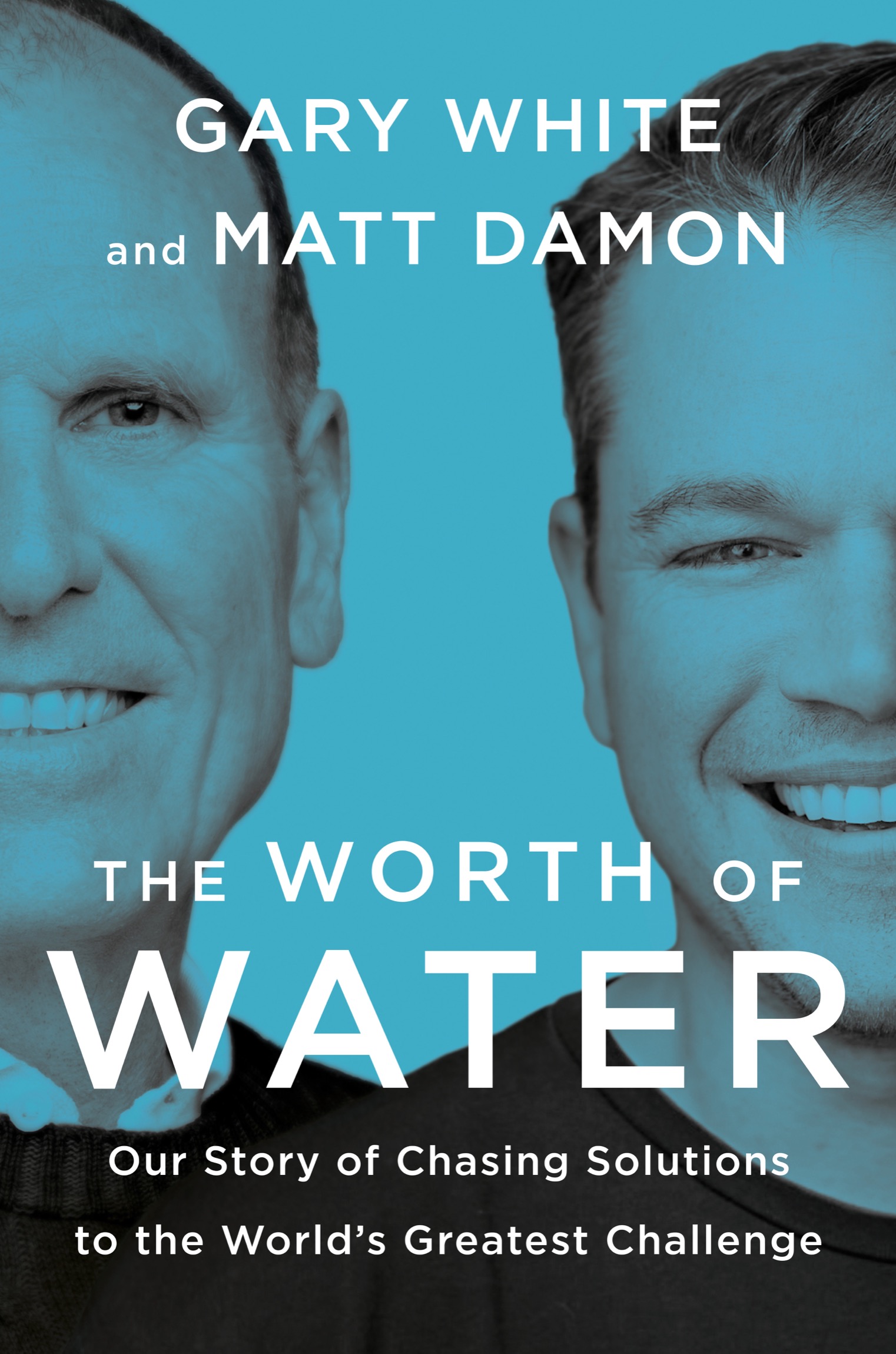

Names: White, Gary (Founder of Water.org), author. | Damon, Matt, author.

Title: The worth of water : our story of chasing solutions to the world's greatest challenge / Gary White and Matt Damon.

Description: New York : Portfolio/Penguin, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021053962 (print) | LCCN 2021053963 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593189979 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593189986 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Water-supplyDeveloping countries. | Right to waterDeveloping countries.

Classification: LCC HD1702 .W48 2022 (print) | LCC HD1702 (ebook) | DDC 333.91009172/4dc23/eng/20211223

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053962

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053963

Cover design: Brian Lemus

Cover photographs: (Photo of Gary White) Erin Patrice OBrien; (Photo of Matt Damon) Sam Jones

BOOK DESIGN BY CHRIS WELCH, ADAPTED FOR EBOOK BY ESTELLE MALMED

Some pseudonyms have been used to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

pid_prh_6.0_139653426_c0_r0

This book is dedicated to the resilient, resourceful, inspiring people we serve. By investing in safe water and all the enormous possibilities it brings, you are charting a new coursenot only for yourselves and your families, but for all humanity.

When the wells dry, we know the worth of water.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

Contents

1

WHAT THE HELL IS THE WATER ISSUE?

POV: Matt Damon

Ive spent most of my life telling stories on-screen, not on the pageso as I was thinking about how to begin this book, I thought about how Id start the movie. Wed fade in on a hut I visited in rural Zambia in 2006. I can still see it clearly in my mind: earthen brick walls, dirt floor, thatched roof. The landscape around it was usually dry, but because this was April, the end of the rainy season, the ground was covered, in parts, with a thin blanket of green. I was sitting outside the hut, waiting for a teenager to get home from school.

I was in Zambia because Bonothe rock star who spends his spare time fighting to end extreme povertyhad been pestering me to go. Pest is Bonos word. He wears it like a badge of honor. He takes pride in getting peoplepoliticians especially, but others, tooto do things they wouldnt otherwise do, if he wasnt pestering them. The guy is really good at it. Bono believes that seeing poverty up close can change a persons priorities, can compel them to go out and do something about it. So he and his colleagues at the organization he started, DATAwhich would eventually become the ONE Campaignhad been pressuring me to join them on a trip to Africa. Hed been pressuring me with the zeal of a telemarketer. He was not going to take no for an answer.

My answer wasnt no, exactly. I just had a lot going on in my life. My wife would be seven months pregnant at the time of the trip, and I had only a small window of time before my next movie. So I told Bono it just wasnt a good time. He looked at me and said, Its never going to be a good time. Which, of course, was totally right.

I had no grand illusions about the point of going on this trip. Its not like Id be changing anybodys life. Bono likes to say that theres nothing worse than a rock star with a cause, but an actor with a cause is a close second. I winced at the mental image of me walking through the bush or an urban slum somewhere, looking concerned, and then flying home to my comfortable life. But then I thought: thats an even dumber excuse for not going than Im busy. The more I thought about the trip, the more I realized that I wanted to go and meet some of the people who live in these extremely poor places, to see firsthand the challenges they face, and to figure out whether there was something I could be doing to help. So I told Bono Id go, and my older brother, Kyle, agreed to come along, too.

The trip was about two weeks long. It took us to slums and rural villages across South Africa and Zambia. DATA had set it up like a college mini course. Each day, we learned about a different challenge that kept people from breaking the cycle of poverty: underfunded health systems, the challenges of life in a slum, the HIV/AIDS crisis. We read briefing books about each issue, visited organizations that were trying to tackle them, and, most important, talked with the people.

On one of our last days in Zambia, we were going to learn about water. It wasnt clear to me why. I understood why we had been focusing on HIV/AIDS and educationthese were issues that you read about in the news, issues that people talked about or signed petitions about or donated in support of. But when I heard wed be spending the day on the water issue, I wasnt sure what issue that was, exactly. I guessed the water was contaminated.

Then I read my issue brief. It said, yes, the water was contaminatedso much so that waterborne diseases were killing a child about every twenty seconds. Then they turn around and carry it home. And the next day they wake up and do it again.

To see what that was like, we drove four hours from Zambias capital, Lusaka, to a village with a well that a partner of DATAs helped build. The staff knew of a family who lived close to the road. Their daughter Wema was fourteen, and every day after school she walked to the well to get water for her family. Shed agreed to let us walk with her, but when we arrived at her home, it was empty. Not just the home, but the whole area. There was no village center that I could see; all the huts were spread out. It was very still, very quiet, and we just sat there for a while, waiting.

Eventually we saw Wema coming toward us down the path. She was carrying books and wearing a simple blue dress that looked like a school uniform. She greeted us shyly, then put down her books and went to fetch her familys jerrican.

At first, as we started walking to the well, the conversation was awkward. Which wasnt really a surprise. Wema, who walked alone to this well every day, suddenly had an entourage of trip coordinators and village officials, plus an overeager movie actor. She and I didnt speak the same language, so we had to rely on an interpreter. Still, as we walked, everybody else hung back a bit, giving us some space. Her responses to my questions were pretty short, but after a while we both relaxed a little, and even the silences felt natural enough. It was a peaceful walk down a country road.

After half an hour or so, we arrived at the well. Somebody suggested I try my hand at it. I had just finished filming one of the Jason Bourne movies, so I thought I was in pretty good shape. But pumping water from this well was harder than it looked. Wema and I laughed as I struggled with it. She had this incredibly practiced way of working the pump and then hefting this big, heavy yellow can up onto her head, where she kept it balanced with the help of one hand. This was easy to admire until you remembered (if youd let yourself forget) that this was work for her: an inescapable, essential chore.

![David E Newton] - The global water crisis : a reference handbook](/uploads/posts/book/104432/thumbs/david-e-newton-the-global-water-crisis-a.jpg)