PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2015

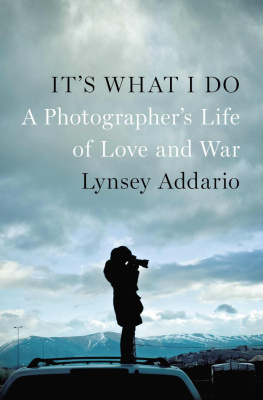

Copyright 2015 by Lynsey Addario

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photograph credits

All images, unless credited below, are by Lynsey Addario.

Pages : Publicly distributed handout, courtesy of Associated Press

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Addario, Lynsey.

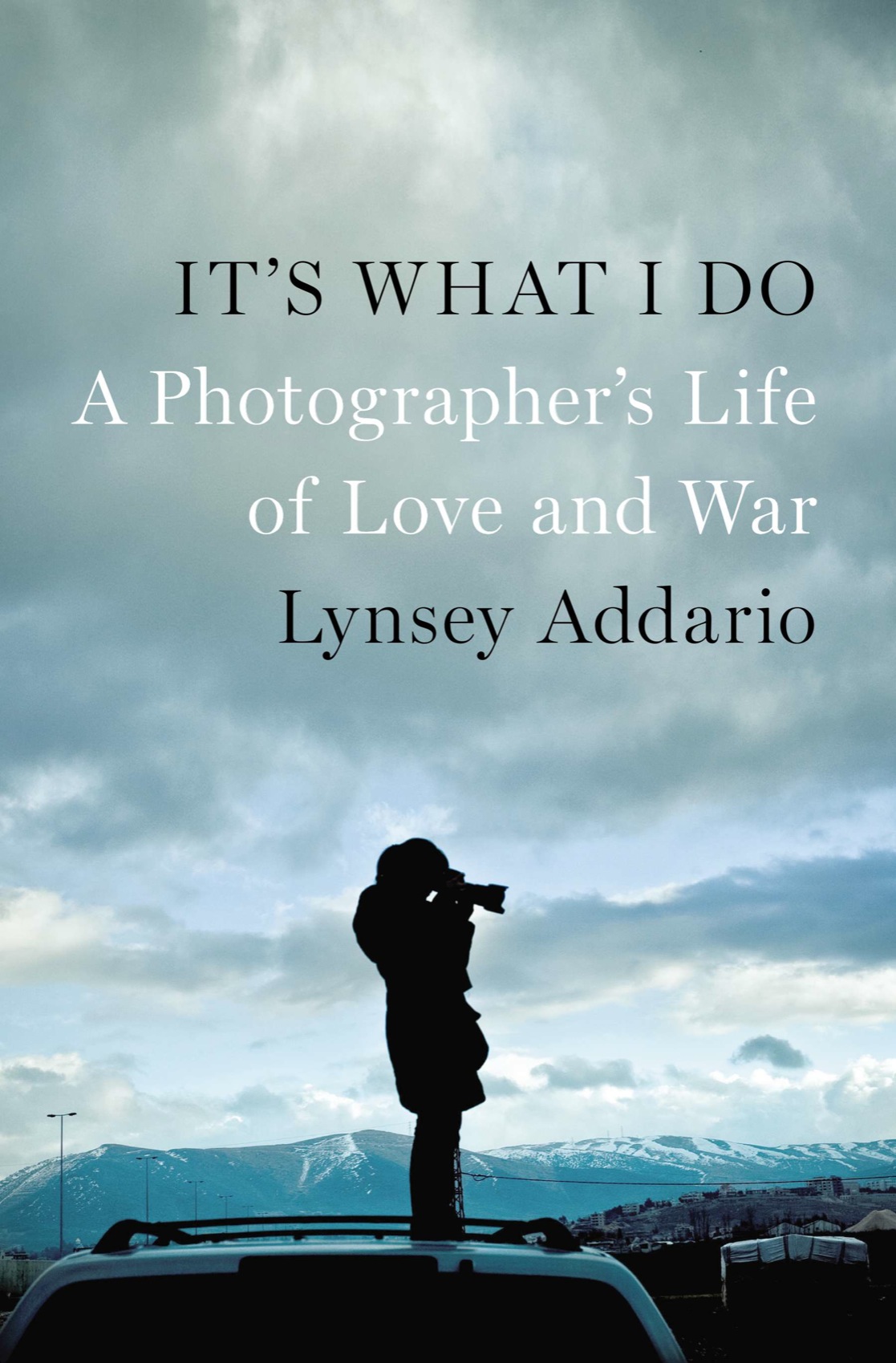

Its what I do : a photographers life of love and war / Lynsey Addario.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-101-59906-8

1. Addario, Lynsey. 2. War photographersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Women photographersUnited StatesBiography. 4. War photography20th century. I. Title.

TR140.A265A3 2015

779.092dc23

[B] 2014036653

This is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some of the names and personal characteristics of the individuals involved have been changed. Any resulting resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Version_1

For Paul and Lukas, my two loves

Contents

Prelude

AJDABIYA, LIBYA, MARCH 2011

In the perfect light of a crystal-clear morning, I stood outside a putty- colored cement hospital near Ajdabiya, a small city on Libyas northern coast, more than five hundred miles east of Tripoli. Several other journalists and I were looking at a car that had been hit during a morning air strike. Its back window had been blown out, and human remains were splattered all over the backseat. There was part of a brain on the passenger seat; shards of skull were embedded in the rear parcel shelf. Hospital employees in white medical uniforms carefully picked up the pieces and placed them in a bag. I picked up my camera to shoot what I had shot so many times before, then put it back down, stepping aside to let the other photographers have their turn. I couldnt do it that day.

It was March 2011, the beginning of the Arab Spring. After Tunisia and Egypt erupted into unexpectedly euphoric and triumphant revolutions against their longtime dictatorsmillions of ordinary people shouting and dancing in the streets in celebration of their newfound freedomLibyans revolted against their own homegrown tyrant, Muammar el-Qaddafi. He had been in power for more than forty years, funding terrorist groups across the world while he tortured, killed, and disappeared his fellow Libyans. Qaddafi was a maniac.

I hadnt covered Tunisia and Egypt, because I was on assignment in Afghanistan, and it had pained me to miss such important moments in history. I wasnt going to miss Libya. This revolution, however, had quickly become a war. Qaddafis famously thuggish foot soldiers invaded rebel cities, and his air force pounded fighters in skeletal trucks. We journalists had come without flak jackets. We hadnt expected to need our helmets.

My husband, Paul, called. We tried to talk once a day while I was away, but my Libyan cell phone rarely had a signal, and it had been a few days since wed spoken.

Hi, my love. How are you doing? He was calling from New Delhi.

Im tired, I said. I spoke with David Furstmy editor at the New York Timesand asked if I could start rotating out in about a week. Ill head back to the hotel in Benghazi this afternoon and try to stick around there until I pull out. Im ready to come home. I tried to steady my voice. Im exhausted. I have a bad feeling that something is going to happen.

Opposition troops fire at a government helicopter as it sprays the area with machine-gun fire. The opposition was pushed back east, out of Bin Jawad toward Ras Lanuf, the day after taking Ras Lanuf back from troops loyal to Qaddafi in eastern Libya, March 6, 2011.

I didnt tell him that the last few mornings I had woken up reluctant to get out of bed, lingered too long over my instant coffee as my colleagues and I prepared our cameras and loaded our bags into our cars. While covering war, there were days when I had boundless courage and there were days, like these in Libya, when I was terrified from the moment I woke up. Two days earlier I had given a hard drive of images to another photographer to give to my photo agency in case I didnt survive. If nothing else, at least my work could be salvaged.

You should go back to Benghazi, Paul said. You always listen to your instincts.

Rebels call for volunteers to fight in Benghazi, March 1, 2011.

A rebel fighter consoles his wounded comrade outside the hospital in Ras Lanuf, March 9, 2011.

Rebel fighters and drivers look up into the sky in anticipation of a bomb and incoming aircraft, March 10, 2011.

Rebel fighters push the front line forward on a day of heavy fighting, 2011.

When I arrived in Benghazi two weeks earlier, it was a newly liberated city, a familiar scene to me, like Kirkuk after Saddam or Kandahar after the Taliban. Buildings had been torched, prisons emptied, a parallel government installed. The mood was happy. One day I visited some men who had gathered in town for a military training exercise. It resembled a Monty Python skit: Libyans stood at attention in strict configurations or practiced walking like soldiers or gaped at a pile of weapons in bewilderment. The rebels were just ordinary mendoctors, engineers, electricianswho had thrown on whatever green clothes or leather jackets or Converse sneakers they had in their closet and jumped in the backs of trucks loaded with Katyusha rocket launchers and rocket-propelled grenades. Some men lugged rusty Kalashnikovs; others gripped hunting knives. Some had no weapons at all. When they took off down the coastal road toward Tripoli, the capital city, still ruled by Qaddafi, journalists jumped into their boxy four-door sedans and followed them to what would become the front line.