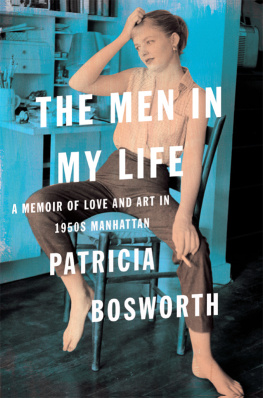

This is a work of nonfiction. The events and experiences detailed herein are all true and have been faithfully rendered as I have remembered them, to the best of my ability. Some names, identities, and circumstances have been changed in order to protect the privacy of those involved.

Though conversations come from my keen recollection of them, they are not written to represent word-for-word documentation; rather, Ive retold them in a way that evokes the real feeling and meaning of what was said, in keeping with the true essence of the mood and spirit of the event.

FOR MOST OF my life Ive been able to hide my feelings; indeed, Id have to say Ive been virtually defined by my ability to hold back. Until now.

I call this memoir The Men in My Life because two of the principal characters are my father, the lawyer Bartley Crum, and my brother Bart Jr.; they were the first men I cared for passionately and who passionately cared for me. When I was very young and struggling to be both an actress and a writer, my brother shot himself in the head, and six years later, my father took an overdose of sleeping pills. How did I survive their deaths? By shutting down completely.

Over the years I filtered my emotions through the biographies I wrote of Diane Arbus, Jane Fonda, Montgomery Clift, and Marlon Brando. I gravitated toward these subjects for good reason. One died by her own hand; another was a suicide survivor. All of them engaged in extremely self-destructive acts. Writing about them was one of the ways I coped with and tried to understand why the two men I loved most in the world had decided to kill themselves.

During the most traumatic years of my early life, I connected in person with three of the artists whose biographies I would eventually write. I was introduced to Montgomery Clift because he happened to be my fathers client. I never forgot his enormous dark eyes or his strange hooting laugh. I suspected he had secrets and I wanted to find out what they were. The same was true with Jane Fonda; we were in classes together at the Actors Studio. Id heard she had issues with her father, but then so did I.

Diane Arbus would be the most mysterious of my future subjects. I modeled for her when I was eighteen. Shed be barefoot, and with her husband, Allan, would duck under the focusing cloth of their heavy eight-by-ten view camera and start whispering conspiratorially before they photographed me. They were a shy young couple, symbiotically close. Their relationship reminded me of mine with my brother. I longed to find out if this was true, and these remarkable people stayed with me in my subconscious as I proceeded on my journey.

I often dont recognize the self I was back then, a skinny girl in leotards and an old duffel coat wandering around New York City. This book is set during a ten-year period in the fifties and sixties (19531963), which on the surface was dark and puritanical, but underneath was a seething ferment of creativity, with painters, poets, photographers, writers, and actors all clamoring to be heard. I longed to be part of that ferment, but I was so spoiled and privileged and in such a daze, its a miracle that I accomplished as much as I did.

Suicide survivors are usually workaholics. I certainly was; I worked nonstop. Many different kinds of men helped me evolve, in many different ways. They were friends and colleaguesin some cases, lovers and husbandsand they were mentors too, like Gore Vidal, Elia Kazan, and Lee Strasberg.

Looking back on it, I cant figure out how I did everything I did because I seemed to be doing everything at once in those days. Before I turned twenty Id earned my first paycheck, opened my first bank account, was in college and auditioning. I loved my independence and reveled in my vagabond existence. The problem was that part of me felt pressured to conform so as to be accepted as a woman; it was the fifties, after all. The push-pull of so many forces, especially from my parentstheir demands and their needs versus my demands and my needsis also very much a part of this story. Slowly but surely I learned how to stand up for myself personally and professionally, and my ambivalence and confusion lessened.

One of the high points of my lifemaybe the highestwas being accepted as a member of the Actors Studio (not to be confused with the TV series Inside the Actors Studio, hosted by James Lipton). At the time the Studio, the birthplace of The Method, was the most influential and talked-about workshop for actors in America. Passing my final audition was a singular honor. I was one of five to be accepted that yearfive out of five hundred.

However, I couldnt participate in classes at first. Since my brothers suicide Id hidden behind a silent, detached facade. Instead Id sit in the back row of the brick-walled theatre, writing down everything I was observing, listening to the Studios master teacher Lee Strasberg as he challenged actors to dig for internal truths. Back then I was a watcher more than a doer. Lee was the first person to encourage me to write. Once he came by as I was scribbling into a notebook and murmured, Darling, maybe you should do what you are doing instead of acting. You seem to be enjoying it more.

Did I hear what he saidreally hear him? No, not yet, because I wanted to prove to him that I could act.

By then I had worked for Lee and hed been surprisingly gentle with me, although we both knew Id been awful. He got tougher with me as time went on. He wouldnt let me get away with faking. He was always talking about behavior, behavior, behavior. Truthful, genuine behavior. Real behavior. I was already acting professionally when I got into the Studio, so I knew how to project externally, but working at the Studio forced me to open up and tap into my inner self. For the next ten years I appeared on Broadway and off, directed by Garson Kanin and Harold Clurman; on TV with George Roy Hill; and then I was featured opposite Audrey Hepburn in The Nuns Story. The memories of these experiences in theatre and film remain vivid to me decades after the fact. Ive always wanted to share them.

But in the end, what Ive needed most is to share the bittersweet recollections I have of my beloved little brother, Bart. He is at the heart of this journey. We were as close as twins. I confided in him, depended on him, adored him. But I cant explain what he did. I refuse to be an armchair shrink.

I dont think Ive been self-indulgent in these pages. I dislike sentimentality. Instead I truly believe Ive shown how the glories in my life outweigh the bleak and terrible. Writing this book has been cathartic. Its finally caused me to feel. Ive cried and cried as Ive written it, but thats good. My emotions were rock-solid for so many years. Now, as I finish The Men in My Life, my body feels lighter. I walk with more of a spring in my step. Ive been carrying around a huge burden of grief and guilt for much too long.

Now its almost gone.

I HAD LEARNED the news in the middle of a dance rehearsal at Sarah Lawrence College; I was choreographing a piece to the tune of Frank Sinatras exuberant Ive Got the World on a String. The studio I was working in was walled with mirrors so I could see the dancers from every angle, twirling and bending, and I could see myself too, skinny then, freckle-faced, serious. Suddenly my teacher Bessie Schnberg was pulled almost bodily out of the studio by the dean of students, Esther Raushenbush, who ordinarily didnt attend dance rehearsals.

Bessie returned moments later with a strange look on her face. She told me I had a phone call I must answer immediately. I ran out into the foyer and the next thing I heard was my father on the line saying, Your brother, Bart, has killed himself with the .22 rifle Granddad gave him for his birthday. He had died in his room at Reed College. He was eighteen.

![Bosworth - Italian Venice: a history[Electronic book]](/uploads/posts/book/194557/thumbs/bosworth-italian-venice-a-history-electronic.jpg)