William Randolph Hearst

The Early Years, 18631910

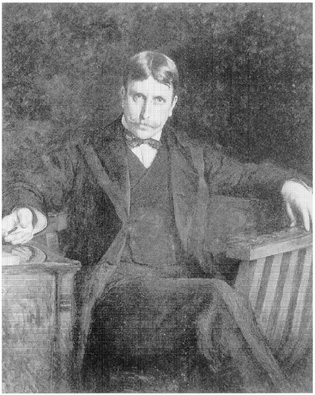

Orrin Peck, William Randolph Hearst, 1894

William Randolph Hearst

The Early Years, 1863-1910

Ben Procter

Oxford University Press

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Bombay

Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam

Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne

Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw

associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Copyright 1998 by Ben Procter

Published by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of Oxford University Press

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Procter, Ben

William Randolph Hearst, the early years,

1863-1910 / Ben Procter

p. cm. Includes Index

ISBN 1-19-511277-6

1. Hearst, William Randolph, 1863-1951.

2. Publishers and publishingUnited StatesBiography.

3. Newspaper publishingUnited StatesHistory19th century.

4, Newspaper publishingUnited StatesHistory20th century.

I. Title

Z473.H4P761998 070.5092

[b]DC21 97-24574

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

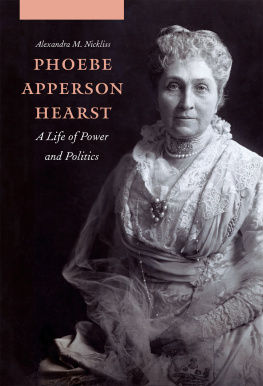

To my wife, Phoebe,

and my son, Ben

Contents

In the fall of 1966 I noticed in the American Historical Association Bulletin that the Bancroft Library (at Cal-Berkeley) had received several hundred letters and other manuscript materials concerning William Randolph Hearstand that more were expected from the family. Although W. A. Swanberg had written Citizen Hearst in 1961, I decided that this new information might warrant an updated biography. Within the next few months I had an opportunity to discuss this possibility with Professor Robert E. Burke of the University of Washington, who in 1950 had been the Purchasing Director for the Bancroft in England. He doused my excitement for this project by stating that papers from the Hearst ware-house in New York City had been trickling in yearly to the Bancroft, but not in sufficient quantityor qualityfor me to anticipate a biography. Thus the matter rested for the time being.

But as Burke knows, I am like an ole dog with a bone. I chew around on itsometimes hungrily, other times by habituntil I decide to let go of it or continue to gnaw. In the case of Hearst the gnawing prevailed. Every six months or so I noticed more Hearst acquisitions by the Bancroft; and each time Burke received a call. His answer was still the samenot enough quantity or quality in the manuscript collection. In the summer of 1976, however, I decided to check for myself and, after spending a week at the Bancroft, I excitedly called Burke, stating that considerable amounts of information in the Hearst papers of the past fifteen years conflicted with Swanbergs book and that a new assessment of Hearst now might be in order. Burke still urged me to postpone the project, but for the first time he was not negative. As a consequence, during a sabbatical in 1981,1 committed myself to this enterprise.

And now after sixteen years of living with Hearst, I feel, at times, that I should have been committed to an institution with padded walls surrounded by verdant fields, where I could sniff the daisies. I should have known better. My Ph.D. dissertation was a biography of John H. Reagan of Texas, who lived from 1818 to 1906eighty-eight years. I pledged during that ordeal that I would never again write a biography, except on someone like William Barrett Travis who was only twenty-seven at the time of his death at the Alamo. Now I have embarked on Hearst who lived from 1863 to 1951the eighty-eight-year syndrome again. Since this work cakes him only to 1910, a second volume will soon be in progress. Obviously I must have masochistic tendencies or a death wishor both.

Despite such protestations, I still find that William Randolph Hearst excites me. And why? He affected the lives of the American people and the policies of presidential administrations. His journalistic efforts created a climate that erupted into the Spanish-American War. And while American historians still debate whether he was responsible for the crusade for Cuba Libre Hearst had no doubts. Day after day in 1898 he proclaimed across the masthead of his New York newspapers The Journals War. His crusades for Progressive causes from 18961910, a fifteen-year period of his life that other biographers have, to a certain extent, overlooked, also influenced the course of American domestic and foreign policies, as well as the day-to-day politics of New York state.

Hearst built a journalistic empire by 1910 that encompassed eight newspapers (and two magazines) in five of the largest cities in the United States with an estimated readership of almost three million people. Equally important, he was an active player in the game of politics; other participants could not afford to ignore or overlook him. Hearst also affected the course of American newspapers, whether for good or evil. Some of what he printed through the Hearst formula of distributing information was purposely slanted or completely fictionalized and sometimes right on the money. In all, his papers were wonderfully exciting and good reading, challenging and innovative and entertaining. Yet, if for no other reason for this study, I have found Hearst to be an intriguing, fascinating personality with sizable frailties, but also with tremendous talent and ability, sometimes bordering on genius. Few individuals in American historywith the exception of certain Presidentshave affected or helped shape the course of this nations history over a fifty-year period, either favorably or wrongly, more than William Randolph Hearst.

Often in this study I became a detective, attempting to separate myth from history while seeking to discover the real Hearst who, in fact, was not averse to distorting actual occurrences or fictionalizing certain events of his life. I therefore decided that the only way to get inside the mind and character of Hearst was to investigate his journalistic creations thoroughly. Hence, I took voluminous notes on the San Francisco Examiner, reading every issue from 1881 to 1895, and April to September, 1906. The same was true of the New York Morning Journal (which eventually became the New York American) from September, 1895, through 1909, balancing the Hearst newspapers with such competitors as the New York World (18961900), New York Times (18981909), and New York Tribune (1898, 1900, 19041909). As a consequence, I spent a tremendous amount of time reading microfilm. I also practiced on-the-scene, investigative research techniques used by such scholars as Francis Parkman and Herbert Eugene Bolton.

Two examples, out of literally hundreds, demonstrate my concern for historical accuracy. At the beginning of my research I discovered that Hearst invented part of his family lineage and history, that George and Phoebe Apperson Hearst, the parents of WRH, were not married in Stedville, Missouri. After visiting the area, I realized that no such place existed, but I did find their marriage certificate that named Steelville, Missouri. Again in the summer of 1989 I visited the site of La Hacienda del Pozo de Verona, which had been the impressive Hearst estate, where Phoebe often resided until her death in 1919. Swanberg, in

Next page