Pattys Got a Gun

Patricia Hearst in 1970s America

William Graebner

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2008 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2008.

Paperback edition 2015

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 3 4 5 6 7

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30522-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-32432-6 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-33807-1 (e-book)

10.7208/chicago/9780226338071.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Graebner, William.

Pattys got a gun : Patricia Hearst in 1970s America / William Graebner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30522-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-30522-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

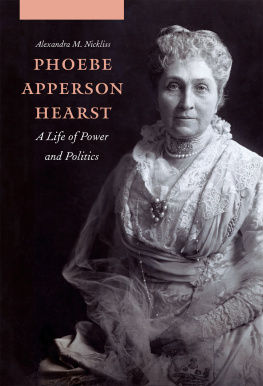

1. Hearst, Patricia, 1954 2. Hearst, Patricia, 1954Public opinion. 3. Hearst, Patricia, 1954Trials, litigation, etc. 4. Symbionese Liberation Army. 5. Trials (Robbery)United States. 6. Kidnapping victimsUnited StatesBiography. 7. KidnappingSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 8. Criminal liabilitySocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 9. United StatesSocial conditions19601980. 10. CaliforniaBiography. I. Title.

F866.4.H42G73 2008

364.15'52092dc22

[B]

2008018320

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Vanessa and Raluca

Contents

Figures

Introduction

Patty Hearsts life changed abruptly at 9 p.m., February 4, 1974, when her fianc, philosophy graduate student Steven Weed, opened the front door of their Berkeley, California, apartment. Two armed men and a woman, members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, pushed their way in. Bitch, one of them said to Patty, better be quiet, or well blow your head off. In less than three minutes, Patty, wearing only a blue bathrobe, had been gagged, blindfolded, and, her hands bound, dragged through the living room, struck in the face with a rifle butt, and forced into the trunk of a car. She had been kidnapped.

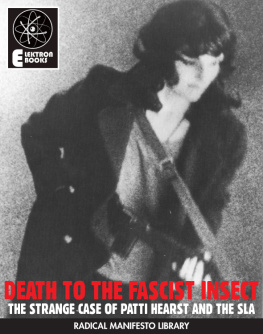

For more than three months following her abduction, Patty Hearstthe nineteen-year-old daughter of Randolph Hearst, son of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst and chairman of the board of directors of the Hearst Corporationheld the attention of the American media, competing for front-page space with the final stages of the Watergate scandal. The SLA released a series of recordings, containing demands and eventually statements by Patty indicating that she now embraced the groups revolutionary agenda. In April, ten weeks after her abduction, she was photographed taking part in the armed robbery of a San Francisco bank. In May the SLA resurfaced in Los Angeles, where six of its members died in a fire following a police standoff. Then Patty and her surviving captorsor comradesdisappeared.

Between February 1974 and March 1976, Patty Hearst was on the cover of Newsweek seven times.

Given Pattys position as an heiress (the noun most frequently used to describe her), her kidnappers flair for publicity, and some of the bizarre things she did while with the SLA, it was inevitable that she would achieve celebrity status. But one facet of her fame was odd, even discomfiting: Patty was dull. Not dull to a fault, and not dull as in stupid. Just ordinary. Short, moderately attractive, living a quiet life of middle-class domesticity in a modest, five-room duplex in a building called the Townhouse on Berkeleys Benvenue Avenue, engaged to be married at nineteen. Weed described their lives as pleasantly routinized with our studies, movies on weekends, laundromat and grocery runs. In summer 1972, at age sixteen, Patty had dutifully set off on a cultural tour of Greece and Italy, only to abandon it halfway through. I hate to admit it, she wrote Steven, but Im terribly homesick.... Venice is nice, but smelly. Rome is really beautiful, but Im afraid to go out of the hotel alonemen dont just whistle here, they run at you and try to grab you! I am even getting tired of looking at all the uncircumcised penises on the statues around here!... I may never open another art book again. The only thing in the world she wanted then, said Weed, was to have two kids, a collie, and a station wagon.

There was dissonance here. One Patty stood to inherit a portion of the Hearst millions, rode her Arabian horse on the familys eighty-six-thousand-acre estate at San Simeon, swam at the Burlingame Country Club, attended boarding schools, and had been raised by nannies in a twenty-two-room house.

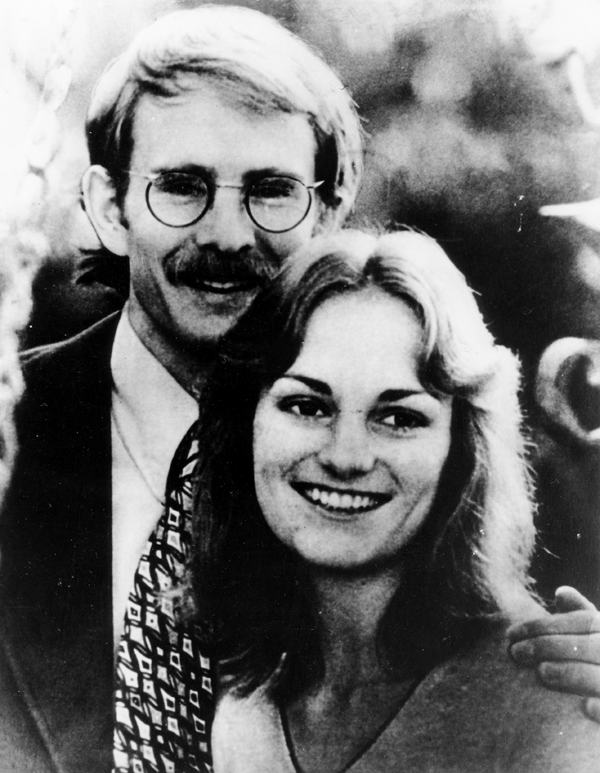

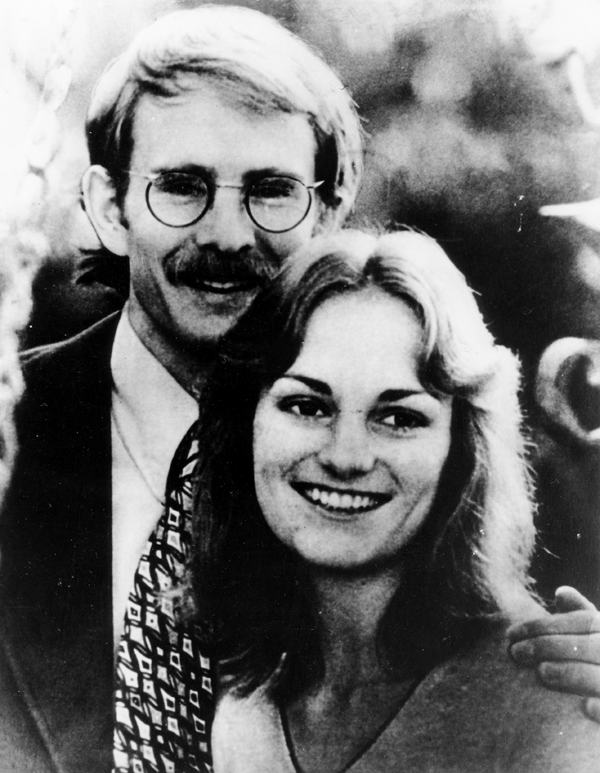

Patricia Hearst and her fianc, Steven Weed, 1973. U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Record Group 65, National Archives.

The problem of the mutable self is an old one, a product of modernitys disruption of a premodern round of life built on community, tradition, and bedrock expectations about ones life and what one could expect from it. The erosion of those comfortable arrangements brought distress and consternation but also opportunity, perhaps best captured in the nineteenth-century celebration of the self-made man.gay community that in 1977 elected the citys first openly gay supervisor, Harvey Milk; Redstockings West and other radical feminist groups; and radical, New Left splinter groups such as Venceremosand the SLA.

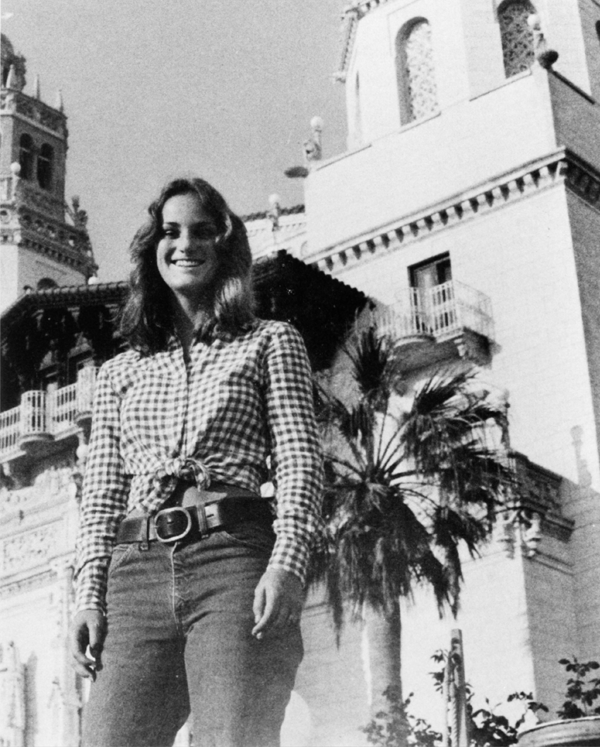

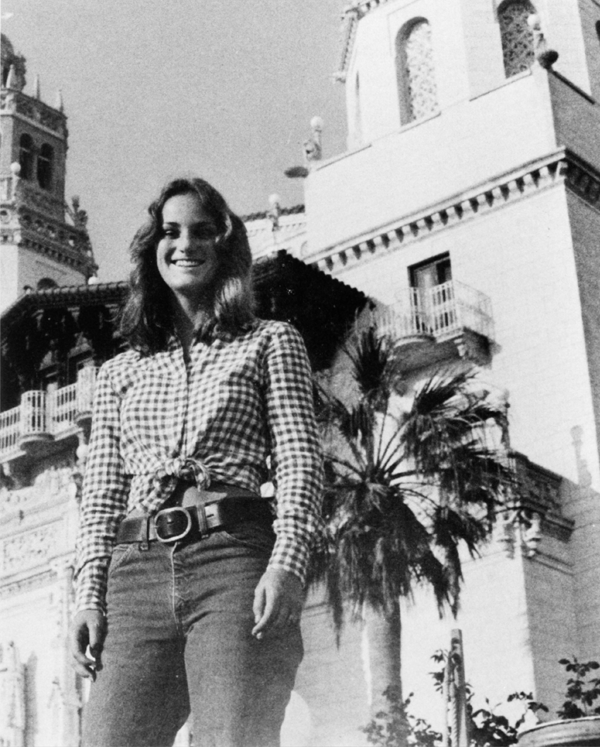

Patty, photographed by Steven Weed in front of La Casa Grande, at her familys San Simeon retreat, summer 1973. Courtesy Steven Weed.

During her trial, images of Patty as an active agent in the creation of her new self came up against her courtroom demeanor, which was passive in the extreme. Anyones Daughter, journalist Shana Alexanders account of the trial, regularly comments

Nor could most Americans. Who was this young woman whose ordinay life and colorless courtroom appearance had been punctuated with nineteen months as captive, bank robber, gunfighter, radical revolutionary, feminist, and fugitive? Was there something extraordinary in Pattys background or makeup that could explain the variety of roles she had taken on in so short a time? Or was this protean Patty a sort of mirror image of the ordinary Patty? And, if that were true, were all ordinary people vulnerable, or open, to such dramatic transformations?

A darker, more threatening explanation for Pattys conduct surfaced frequently during the trial, although, in the end, it did not carry the day. Perhaps the SLAs treatment of Pattythe violent kidnapping, the sexual abuse, the constant threats, the program of indoctrinationhad changed something inside her, made her compliant, willing to do anything. Reduced to this state, she resembled others who had been broken by their captors and made to do and say things contrary to conscience and character: pilots captured during the Korean War, concentration camp prisoners, and Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty, a Hungarian prelate who in 1948 penned a confession after thirty-nine days of abuse in a Communist prison. In this scenario, Patty hadnt chosen anything, except, perhaps, to stay alive; rather, she was the helpless victim of a powerful new system of mental and physical manipulation.

Was Patty a victim, of duress or fear or what the defense labeled coercive persuasion, or had she taken up with the SLA willingly, decided to be a different person, chosen a new life? Did Pattys engagement with the SLA have a historical or social cause (the sixties and growing permissiveness were among the favorites), or was her interior lifethat is, her free willsufficient to explain her conduct? If Patty had in some sense been taken over, if she had been brainwashed, turned into a zombie, converted under duress, or otherwise deprived of free will and full consciousness, were other, ordinary Americans, regardless of race, class, gender, and circumstance, just as vulnerable? Should they understand themselves, deep down, as potential victims or as free agents?

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).