All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publisher, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

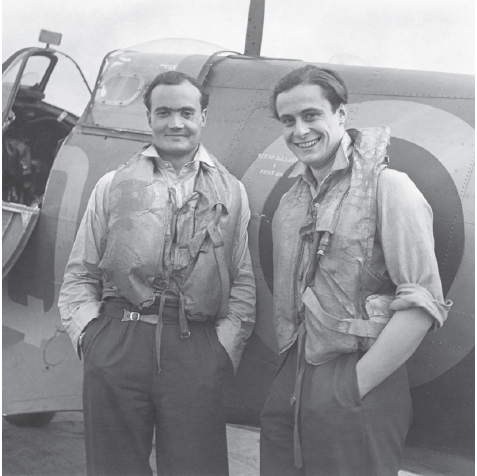

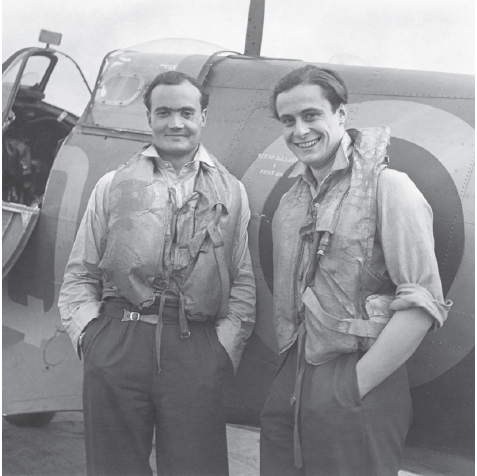

Flying Officer Geoffrey Wellum (right), with Flight Lieutenant Brian Kingcome, next to a Spitfire at Biggin Hill, 1941.

T HE FIRST TIME I EVER SAW a Spitfire, the voice of authority bade me to go out there and fly it, and on no account break it. Straight out of flight training with only 146 hours total flying experience, of which 95 were solo, I might have been forgiven for viewing the situation with a certain degree of apprehension. But there she stood graceful, elegant and relaxed.

Once strapped into the cockpit, the Spitfire somehow had a friendly atmosphere about it, albeit a little confined. Nevertheless, I felt immediately part and parcel of the aeroplane and totally at ease. It was then that I realized what a privilege it was to have been chosen to fly one at such a crucial time in our history.

The view forward from the cockpit was restricted to say the least, due to the long nose and the narrow undercarriage, which gave it an unstable feeling during taxiing. But once in the air it was an entirely different matter. She was a thing transformed light and responsive to every control input, the Spitfire seemed to slip through the air.

There were no vices and it became quite obvious to me what a truly magnificent design it was for a single-seater fighter aircraft. It says so much for the whole design concept of the Spitfire that when a young and impressionable pilot of nineteen, direct from training, could get into one, fly it in combat and in most cases make a safe return. It cannot be overstressed how fortunate it was that Spitfires arrived in squadron service just in time for the Second World War.

There has been much written concerning the iconic Spitfire, but Spitfire Stories approaches the subject from a refreshingly different angle, and I wish it every success.

Geoffrey Wellum

92 Squadron Biggin Hill

T HE IMAGE IS ICONIC AND THE history one of wartime victory against the odds. Yet in many ways, the advent of the Supermarine Spitfire was a minor miracle in itself.

The authorities of the early to mid-1930s could not be accused of having any sense of urgency when it came to developing Britains air defences, or re-arming after the First World War in the event that another world war could be possible. The First World War was often described as the war to end all wars, and its brutality and horror left governments terrified at the prospect of further conflict. The 1930s was also a period of economic recession and unemployment in Britain; resources were scarce and most politicians did not wish to spend money on armaments. While Churchill saw the looming threat of Hitlers rise to power, many in the British government remained anti-war.

Britains aviation industry was seriously under resourced and the Royal Air Force (RAF) had been greatly reduced in size, with very little being spent on aircraft development. Back in 1918, Britain had boasted the worlds strongest air force. Yet by the early 1930s, the country was ranked fifth amongst the worlds leading air powers. By the mid-1930s, the encroaching threat of war with Hitlers Germany could no longer be ignored: Germany was re-arming and the Luftwaffe was expanding at a much faster rate than the RAF. As a consequence, prototype new fighter planes the Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire were ordered for the RAF at the end of 1934. By the end of the 1930s it was obvious to many countries, including Britain, that Hitler had built up a mighty war machine.

The first Hurricane prototype took to the skies in November 1935, and the Supermarine Spitfire soon followed. The Spitfires original designer, R. J. Mitchell, had designed many planes for aircraft manufacturer Supermarine by the time of its auspicious first ever test flight in March 1936 with Vickers Aviations chief test pilot, Captain J. Mutt Summers at the controls. Yet this was no instant success story: Mitchells original design for a new fighter plane (dubbed The Shrew) designed to the exact specification of the Air Ministry, had originally been tested in February 1934 by Summers. Unfortunately, the planes cooling system let it down and it failed to impress.

Undaunted, Mitchell returned to the drawing board. This time he bypassed the Air Ministry specifications to design a thinner elliptical wing, a smaller span and a cockpit with a Perspex cover. Plus, of course, a distinctive Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. His Spitfire plane wowed the watching air marshals and won the day. Yet although the successful Spitfire test flight an acknowledged turning point in aviation history led to a contract being issued in June that year for Supermarine to produce 310 Spitfires, the frontline operational strength of the RAF remained pitifully weak when compared to that of Germanys Luftwaffe, and it was not until 1940, after war had been declared, that Spitfire production really got going. Sadly, Mitchell never knew the true success of his inspirational design as he died just one year later from bowel cancer, aged only forty-two. A year later the Spitfire entered RAF Squadron service, delivered to 19 Squadron at Duxford. The subsequent development of the Spitfire from that initial Mark I pioneer through to twenty-four different Spitfire types or marks was due to the talents of the Supermarine team, headed by Joe Smith, Mitchells successor as Chief Designer.

Even in those early war years, however, it had still been touch and go when it came to getting the plane off the production line: in May 1940, for instance, the Air Ministry came perilously close to cancelling orders because the Spitfire required a lot of hand-building and finishing, making it more costly than anticipated. But the orders were completed and, that same month, inspired by the efforts of Canadian media tycoon Lord Beaverbrook (Max Aitken), Spitfire fundraising to build the planes 5,000 per Spitfire was the figure given at the time took off at breakneck speed across Britain and around the world.