SCENIC

IMPRESSIONS

SOUTHERN INTERPRETATIONS from THE JOHNSON COLLECTION

SCENIC

IMPRESSIONS

SOUTHERN INTERPRETATIONS from THE JOHNSON COLLECTION

ESTILL CURTIS PENNINGTON & MARTHA R. SEVERENS

THE JOHNSON COLLECTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH

THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS

The Johnson Collection, LLC, 2015

The Johnson Collection

PO Box 3524, Spartanburg, South Carolina 29304-3524

864.585.2000 thejohnsoncollection.org

David Henderson, Director

Sarah Tignor, Collection Manager & Registrar

Lynne Blackman, Public Relations & Publications Coordinator

Aimee Wise, Collection Assistant

Holly Watters, Collection Assistant

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise noted, all images are property of the Johnson Collection, LLC.

Copublished in partnership with the University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, South Carolina 29208.

800.768.2500 www.sc.edu/uscpress

Editor: Lynne Blackman

Photography: Carroll Foster, Hot Eye Photography, Spartanburg, South Carolina; Tim Barnwell Photography, Asheville,

North Carolina; Rick Phodes Photography and Imaging, LLC, Charleston, South Carolina

Design: Gee Creative, Charleston, South Carolina

Production: Printed in Canada by Friesens

ISBN 978-1-61117-675-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

This volume accompanies the exhibition of the same title. Exhibition venues include:

Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tennessee

Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, Georgia

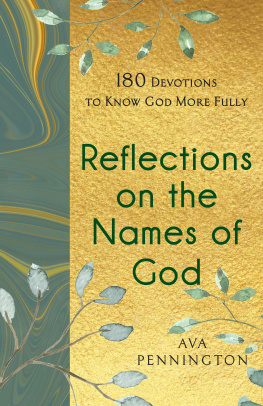

Frontispiece: Alice Ravenel Huger Smith (18761958), Swamp Scene, watercolor on paper, 21 x 11 inches (detail).

Cover: Hattie Saussy (18901978), Path with Mossy Trees, oil on canvas mounted on masonite, 18 x 26 inches (detail).

ISBN 978-1-61117-717-6 (ebook)

Contents

DAVID HENDERSON

KEVIN SHARP

ESTILL CURTIS PENNINGTON

MARTHA R. SEVERENS

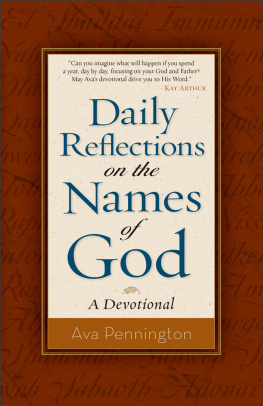

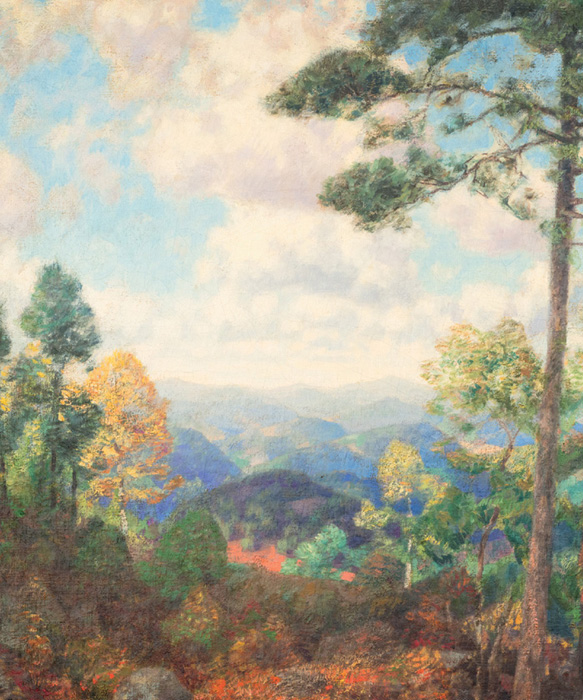

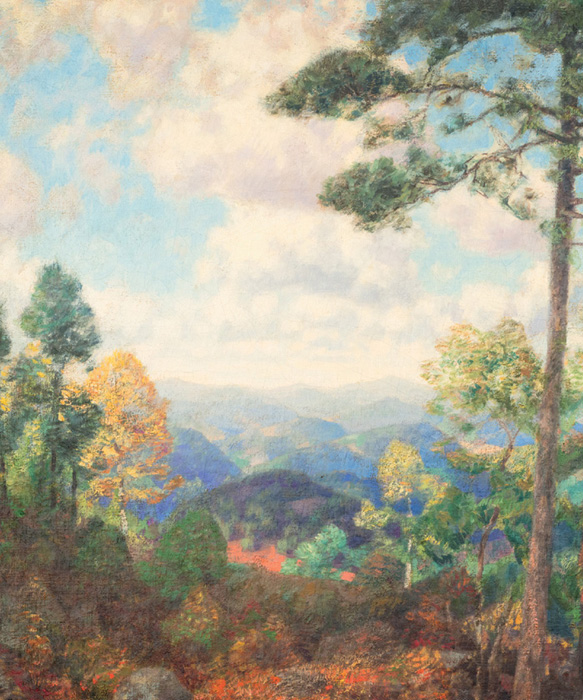

Lawrence Mazzanovich (18711959), Smoky Mountains, oil on canvas, 25 x 25 inches (detail).

Preface

IN THIS DAY OF THE EVER-PRESENT CELL PHONE CAMERA, IT MIGHT BE difficult to imagine the efforts that artists once made to record a memorable view for posterity. Preparation required far more than the overnight charging of a battery or the availability of GPS monitoring. Travel was arduous and conveniences were limited, as was a reliable clientele or lucrative commercial infrastructure, especially for painters working in the South. No, the artists presented in this study invested considerable intention to the discovery and delineation of places of particular beauty. Whether the setting was extraordinary or everyday, artists hoping to capture the moment went to great lengths to provide their patrons with scenic impressions that transcribed venue, color, and mood. The experience was a physical and tactile one, and the connection between artist and locale deeply felt. The best paintings reflect such synergy and reward the effort.

Intention, location, connection, and synergy have been driving forces in the establishment of the Johnson Collection as well. In just over thirteen years, what began as aesthetic experiment has evolved into cultural statement. To amass a collection (of any sort, really) according to well-defined parameters is fairly straightforward; it can be, at its most fundamental level, purely transactional. What sets meaningful and significant collections apart is effort: the willingness to dig deeper, to discern carefully, and to never settle. A command of the history in question is important, but personal resonance with that history is indispensable, even for a transplanted Canadian like me. In guiding the collections acquisitions, my understanding of market conditions has been imperative, but so has the awareness that true value is often determined by far less tangible measurements than price-per-square-inch calculations and sales records. The Johnson familys vision, and fidelity to that vision, is more critical to the collections vitality than their endowment. That they have allowed me to pursue my passion for Southern art in the collections name has been a privilege. It has given me a proverbial second act rich with revelation and joy.

As the collection evolves, developing nuance and depth, it remains true to its original mission to advance the narrative of Southern art within the national cultural context. Scholarship on the subject is paramount, as evidenced by this, our third volume in as many years. We will continue to interpret the South and champion the cause with an eye toward making an ever clearer impression on the field of American art.

DAVID HENDERSON

DIRECTOR, THE JOHNSON COLLECTION

SPARTANBURG, SOUTH CAROLINA

Foreword

I REMEMBER A TIME WHEN WE ALMOST NEVER DISCUSSED AMERICAN Impressionist painting. The French inventors of the movement, style, and technique (or whatever it was) were so much riper in their way; their pictures just had more air in their lungs, as I heard one colleague describe the difference years ago, and I agreed. At the time, we were not entirely sure what American Impressionism wasor even if such a thing truthfully existed. When we finally did start talking about American painters of the Impressionist eraneatly avoiding the term American Impressionism, which we distrustedthey were typically the grand expatriates. We sought American artists who had opened studios or planted easels alongside their counterparts in England, Holland, or (of course) France, and had the good sense to remain there. We discussed this mere handful of painters for the longest time, and in nothing less than excruciating detail. Actually, we are still discussing them. It was only latermuch later, in factthat we became interested in the (so-called) American Impressionists, who lived their lives and managed their careers within the boundaries of the United States. We preferred them to have made at least one extended trip to Paris, or to Giverny, or both. And we were only willing to seriously consider artists who after returning from their French sojourns established themselves in New York studios or with notable Manhattan galleries, clubs, or institutions. Granted, we eventually came around to Philadelphia, Boston, and much of New England as well, but there we had to draw the line.

From the massive and magisterial book, American Impressionism (1984) by William H. Gerdts, we came to understand that there had been artists in every corner of the United Statesnot just the Northeastwhose paintings undeniably resembled Impressionism. By the time his Art Across America was published six years later, the number of painters he identified further afield had grown considerably (especially in Volume 2, which catalogues Southern and Midwestern artists). But how were we to account for these artists in the context of Impressionism? Some of them had never left the towns in which they were born, let alone traveled to Giverny. It was puzzling, and easier to dismiss their efforts as mimicry than to contend with it as expression. So, rather than contend, we ignored it.

It turns out that we were spectacularly and even proudly parochial in our likes and dislikes about Impressionism. It turns out that by focusing so intently on our preference for riper artists with lungs full of air, we were missing one of Impressionisms more intriguing qualitiesits remarkable durability as an international style and especially its longevity in the United States. Decades after most French painters were exploring other movements, styles, and techniques, it turns out that American artists were continuing to extract expressive value from the Impressionist aesthetic. Even if they later abandoned Impressionism for something altogether different, American paintersfully two generations of them, at leastsaw it as a well lit pathway toward the vanguard. And it happened border-to-border, coast-to-coast.

Next page