God Save The Kinks

When I first heard Village Green Preservation Society in 1971, I got this picture in my head of small-town English life: village greens, draught beer. But when R.E.M. went to England in 1985, I drove through Muswell Hill and it certainly wasnt romantic looking. From Waterloo Sunset, I had this picture of a gorgeous vista when its really a grimy train station area. I realised these songs were all acts of imagination, that Ray was commemorating an England that was slipping away. There is a great air of sadness in those songs.

Peter Buck, R.E.M.

After half a century of performing, Ray Davies was preparing for the biggest event of his life. He was backstage at a stadium in London as 20 million UK viewers and an estimated worldwide audience of 750 million tuned in to watch the closing ceremony of the biggest sporting event in the world, the London 2012 Olympic Games. Titled A Symphony of British Music, the 20 million production utilised more than 4,000 people and a host of high-profile performers. Ray Davies segment was to be at the centre of the show and he was to sing his most famous song live. But things werent going to plan and, as his appearance on stage grew closer, he was still unhappy about the set up. [The earpiece] wasnt working when I was cued to go on, he recalled. I said, Im not going on. He was told he had no choice. This isnt fucking well working, he replied. I could just hear this crackling in my ear, he remembered. And I said, Excuse me, its still not working, and they slammed the door in my face! I didnt know till I opened my mouth whether anything would come out.

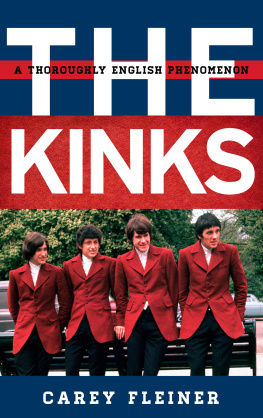

The Kinks have been around for a long time. Their first attempts at making music date back fifty years and their story encompasses distinct phases and metamorphoses: early Merseybeat imitators, British Invasion leaders, late-sixties innovators, concept album champions, new-wave godfathers and, now, revered elder statesmen. The Kinks may have split up in 1996, but they have never really left us. In fact, the past few years have seen their influence grow and grow. Box sets, movies, stage shows, documentaries, deluxe album re-issues and, of course, books have all continued the task of securing their place in rock and roll history, alongside The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, as one of the founding acts of modern pop.

My own first recollection of The Kinks dates from the mid-1970s, when I used to play with my mums collection of 45 rpm singles. Just about old enough to operate her ancient portable record player, I scratched the discs to pieces in the process, but, at the age of six, it was a great education to get my hands on the songs of The Beatles, The Hollies and The Kinks, whose characters struck a fairy-tale chord at a time when my friends were listening to novelty offerings from The Wombles. I didnt know who had created this wonderful music, and The Kinks didnt stand out, but evidently the songs lodged somewhere in my memory.

Fast-forwarding to 1983, by which time I was at secondary school, I heard a song called Come Dancing. It wasnt the hippest record I heard that year, but it was incredibly catchy, and it was almost impossible to disobey the instruction in the songs title: it made me want to move my feet. I had no idea this was the same band that had written You Really Got Me, Waterloo Sunset and Sunny Afternoon two decades earlier songs Id played to destruction on my mums old record player.

A few years later, when I was in the sixth form, The Kinks briefly became fashionable again, at least in my immediate social circle of mainly U2 and R.E.M. fans. I went out and picked up a Greatest Hits LP and discovered the extent of their genius. At that moment, I became a fully-fledged enthusiast; a worshipper, in fact.

As I ventured beyond the Greatest Hits, buying the albums and learning more about the band who made them, I discovered The Kinks sprang from a particular time and place, and that their story is that of a culture now fading from memory. They stand for individualism and for the best of what it means to be English; they made a career out of the act of observing, recording and remembering things that were both ordinary and important. They were a product of bomb-scarred post-war north London and that, more than anything else, has defined who they are. Theirs is a tale in which a group of young, ambitious and often angry working-class men take on the music establishment not always successfully as they battle along their own eccentric path to stardom.

Brothers Ray and Dave Davies, as principal songwriters and vocalists, have always been at the heart of this story, and at the centre of attention, especially when they engage in their characteristic feuding through the press. But the supporting cast of Pete Quaife, Mick Avory, John Dalton, John Gosling and many others, were essential to making The Kinks what they were: an extremely talented, sometimes infuriating band with killer tunes and a clever turn of phrase.

More than The Beatles, the Stones or The Who, The Kinks were an English band. Their music defied easy categorisation. After early dabbling with Merseybeat and American-influenced R&B, they ceased to follow trends, choosing instead to pursue what sometimes seemed like wilfully weird avenues, but often leaving new genres in their wake.

Ray Davies is a songwriter who has often seemed to have too much on his mind, but there is humour in the songs, albeit black. Life is hard comes the message, and The Kinks certainly missed plenty of opportunities and had a knack of finding a way to lose when a win looked inevitable. They spearheaded the British invasion of the United States, then got themselves banned at the very point when they looked poised to take America by storm. But their enforced dedication to the English scene gave Ray the chance to write some of the bands best albums and, after some potentially calamitous personal crises in the early seventies, the group went down the road of theatrical rock opera productions before a new burst of enthusiasm from the US made them unlikely stadium stars in the eighties.

The songs that have stood the test of time and lingered in the popular memory are often sharply focused character studies portrayals of mundane English life made significant by Ray Davies natural ability to focus on details that others would have missed. They are tales of class conflict, of envy and struggle. Stories of the streets, of family, of home. Working-class suburbia never sounded so good. Though they werent the only musicians from London The Who, The Small Faces, Sandie Shaw and The Dave Clark Five were among their contemporaries The Kinks, more than any other band, made their home city the very subject of some of their most memorable songs, and thus kept it on the pop music map.

Today, The Kinks are the most likely of all the great 1960s bands to be cited as an influence by the hippest of the younger generations of musicians, seen as a more discerning choice, perhaps, than the ubiquitous Beatles. In the past two decades, Oasis, Blur, The Kooks, The Pixies, and The Killers, to name but a few, have all highlighted The Kinks lasting importance. Theyve also cropped up on the soundtracks of quirky, cool films like Rushmore and Juno.

For all that, of all the sixties giants, they are perhaps the least known recognised by most people only for their hit singles, despite an endless list of musically magnificent non-hits, B-sides and album tracks. Theyve sold more than 50 million albums worldwide, and were ranked at number five on Rolling Stone magazines list of top ten rock bands of the twentieth century, and yet The Kinks remained relatively under-appreciated for a surprisingly long time. In fact, being under-appreciated is almost part of their brand: even when they were producing memorable albums such as