LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

No, Kum-Sok.

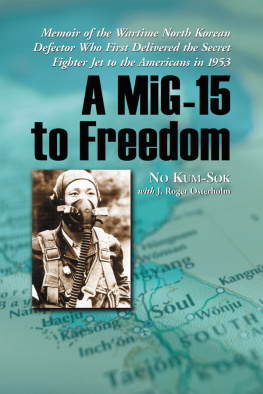

A MiG-15 to freedom : memoir of the wartime North Korean defector who rst delivered the secret ghter jet to the Americans in 1953 / by No Kum-Sok, with J. Roger Osterholm.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-3106-9

1. No, Kum-Sok. 2. Korean War, 19501953Personal narratives, Korean. 3. Air pilots, MilitaryKorea (North)Biography. 4. Korea (North) Air Force Officers Biography.

I. Osterholm, J. Roger. II. Title.

DS921.6.N6 2007

951.904'2'092dc20 [B] 96-27288

British Library cataloguing data are available

1996 Kenneth H. Rowe (No Kum-Sok) and J. Roger Osterholm. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: No Kum-Sok in his ight gear, September 21, 1953, Kimpo Air Base; detail map of Korea 2007 Photodisc

McFarland & Company, Inc.,

Publishers Box 611,

Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the memory of ve dear comrades in arms,

Lieutenant Kun Soo-Sung and four other North

Korean ghter pilots, who many times to the last

day of the Korean War entered into air combat

alongside my MiG-15 against United Nations

aircraft. The crime of those responsible for

executing these ve innocent North Korean

yers shortly after my defection to the Free

World shall never be forgiven nor forgotten.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my gratitude to the Jack Hunt Memorial Library, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach, Florida, for the use of its collections. The Philadelphia Bulletin generously gave me access in 1955 to its clippings file. I wish to thank the following individuals for their assistance in this project:

Joseph L. Massie, alumni professor emeritus at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, for the earliest advice on writing and help on early drafts;

Ralph G. Anderson, founder and CEO of Belcan Corporation, Cincinnati, Ohio, for encouragement and help in researching publishers;

Paul Braim, Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, for special encouragement, military history, and advice, and for a helpful review of most of a late draft;

Cheryl Malely, department secretary, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, for help with a word processor;

Reinhold Schlieper, humanities professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, for his computer expertise;

Diane J. Osterholm for proofreading and encouragement;

Bonnie C. Rowe, my daughter, for encouragement, a close reading of drafts, and many useful suggestions;

Edmund H. Rowe, my younger son, for special encouragement, reviewing a draft, and suggestions of topics to cover;

Clara E. Rowe, my loving wife, for her tireless support, for reviewing the drafts, and for valuable suggestions.

Preface

Almost every clear flying day I woke at 5 A.M. and by 6 A.M. took off from the air base at Dandong, Manchuria, the base to which North Korean aircraft fled after B-29 night raids destroyed every airfield in North Korea. I flew to meet U.S. F-86 Sabres in the skies of MiG Alley, which included the area over the Supung Dam and the city of Sinuiju on the Yalu River. Flying in close formations of sixteen to twenty-four MiGs, we met groups of two to four Sabres flying in loose formation in the clouds. When our tight formations were broken up by the attacking Americans, those of us remaining aloft turned and fled back across the Yalu to the privileged sanctuary of Manchuria, where American pilots had been ordered not to follow. As the aerial combat progressed into the spring of 1952, however, the Americans became more aggressive, and, eventually, the sanctuary was no longer observed by the Americans. The daily dogfights expanded into the skies of China in southern Manchuria.

In the afternoons after these engagements, I stood at attention at nonreligious Communist funerals for my fellow Red pilots who had been sacrificed in a bloody air war against better-trained Americans flying the superior Sabrejet. Before the Korean conflict was over, American air murderers, as the Communists called them, had destroyed more than 700 MiGs, almost a 100 percent turnover of all our Red air forces in Korean combat.

I fought as well as I knew how for Red Korea. As a captive of an elaborate system of thought control developed by Asiatic Communists, I had no choice. I was twice decorated, with the Red Flag Medal and Gold Medal. I was considered an enthusiastic and inspired young Communist by Lieutenant General Wang Young, commandant of the North Korean air force, and by many others, down to my mechanic. I was vice chairman of my Second Battalion Communist party, squadron commander of four jet fighters, and the only pilot in my division whose MiG bore the treasured Youth Organization Seal. Articles about my flying skill and my devotion to Communism, along with my photograph, appeared in Red magazines and newspapers.

All that time I was living a gigantic lie. From the day I realized my country had become a Communist state, I carefully cloaked myself in the protective garb of Communist loyalty. I shouted Red slogans, berated true Communists for not hating the enemy enough, and practiced Marxist antics with more apparent zeal than my comrades.

I had never heard of General Mark Clarks $100,000 offer for a MiG. Since 1948, North Korea had been completely shut off from the Free World. Even the dials of our private radios in the barracks were fixed so that we could receive only the official government station at Pyongyang. On September 21, 1953, the first flying day at the rebuilt air base near Pyongyang, I abruptly turned south and 13 minutes later landed on an American runway from the wrong end while an F-86 Sabre landed from the other end at the same time. After surviving that hairy landing, I could only hope desperately that the stories I had read in my childhood about the Free World were true.

Soon after that day I worked as a United States Air Force technical specialist on Okinawa and answered thousands of questions about Red air strength for the United States Far Eastern Air Intelligence. My MiGnow in the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohiowas shipped to Okinawa, where it was flown by famed test pilot Major Chuck Yeager (now a retired brigadier general) and others, who confirmed what I found out in combatthat it was inferior to the Sabrejet. The other test pilots were Major General Albert Boyd and Captain Harold E. Tom Collins; the latter is now a retired major general.

The backbone of the Red air forces in the Korean War was the Russians. They were not really volunteers but members of regular jet divisions of the Soviet air force from Moscow defense units who were pressured to volunteer out of patriotism and to avoid being thought cowardly. They had been sent into combat by Generalissimo Stalin to stem American air superiority. The Russians had been able to keep their participation and defeat in the Korean air war a tight international secret only because the jet fighting took place over Red-controlled territory. After each air battle, the Soviet air force quickly recovered its destroyed MiGs and dead pilots.

In 1953 the Reds agreed to a cease-fire, fearing that newly elected President Eisenhower would launch an amphibious landing, similar to the Normandy Invasion of 1944, against North Korea. I saw the Reds break the Korean truce the day after it was signed, however. For weeks after the cease-fire, I saw MiG fighters on railroad flatcars being illegally shipped across the border from China into North Korea.

Next page