To Sophie, with love

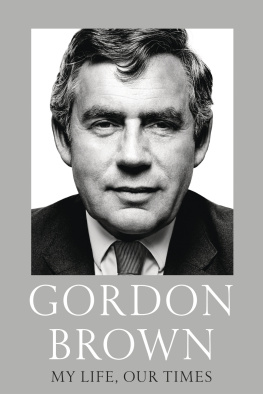

Their laughter was raucous. Seated in the Club section of the British Airways aircraft, the ten men were bonded by their love of football and their anticipation of a laddish weekend in Rome. Five months after the general election, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer was laughing with his intimate gang. There was much to celebrate.

On Saturday, 11 October 1997, England was playing Italy in a qualifying match for the World Cup. The valuable tickets for the game had been obtained for the group by Geoffrey Robinson, the paymaster general, as a favour to Gordon Brown, who was seated in the front of the jet. The prospect of football, beer and banter in Rome appealed to the former schoolboy footballer. The game was a males world, an emotionally satisfying conclave excluding women. The weekend would also be an opportunity to develop relationships with journalists, whose sympathetic reports about his successes would enhance his reputation and help his dream to become Britains prime minister. Brown, the host of many noisy parties during and after his student days in Edinburgh, enjoyed the mixture of politics and sport.

The invitations to the journalists had been issued by Charlie Whelan, the chancellors sparky press spokesman, who was seated near Brown. Over the previous years Whelan had regularly offered friendly journalists tickets to special football matches and issued invitations to memorable parties before international fixtures in Robinsons flat at the Grosvenor House Hotel in Park Lane. Oh, Geoffrey, quipped Brown as they flew over Tuscany, your villa is down there. We should have a campaign: one villa one vote. The reference to the villa controversially loaned to Tony Blair and his family during the summer triggered more laughter. Brown had been in good form ever since they assembled at Heathrow. Whats the difference, he had asked as they waited for the plane, between Jim Farry [the chief executive of the Scottish Football Association] and Saddam Hussein? One is an evil dictator who will stop at nothing, and the other is the leader of Iraq. The banter was joined by Ed Balls, the chancellors personable and intelligent adviser, and the fourth of the quartet Brown, Robinson, Balls and Whelan. Ballss eminence in the Treasury was resented only by the envious and the defeated. The thirty-year-old was the intellectual guide of the chancellors conversion from a traditional socialist to the mastermind of New Labours appeal to the middle classes. Since Labours landslide victory Balls had become guru, gatekeeper and deputy chancellor in the Treasury.

The four had unashamedly fashioned their capture of the Treasury as storm troopers assailing a conservative bastion, revolutionaries expelling the old guard. Over more than a decade Gordon Brown had plotted and agonised to achieve that coup. Disputes and distress had marred the route to 11 Downing Street, and five months after his victory the new, unconventional inhabitants of Whitehall incited malicious gossip about the introduction of bull market tactics into Westminster politics, prompting Blairites to accuse Brown of behaving like a Mafia godfather, an accusation he resented.

The only unease among the six journalists was caused by their Club class tickets, each costing 742. Geoffrey Robinson had privately settled the account, leaving a suspicion that the journalists would not be pressed to repay. His guests briefly considered the millionaires motives. Robinsons ebullience made the trip feel like one of those louche jamborees organised by public relations companies for anxious clients. His fortune, earned in suspicious circumstances and concealed in offshore banks, had financed Browns private office before the election. For any politician to be associated with Robinson provoked questions. The journalists judged that the chancellor was not suspicious about the motives of their host, whose generosity had relieved the Scotsmans social isolation in London. Nevertheless, before the jet landed, some resolved that regardless of Charlie Whelans inevitable scoffs, their fares would be reimbursed, with a request for a receipt.

The laughter halted. Gordon Brown, dressed in his customary dark suit, white shirt and red tie, fumed, Do you know theyve sold the Scotland match against Latvia to Channel 5, and only half of Scotland has Channel 5? The admirer of Jock Stein had travelled to see Scotland play in Spain during the 1982 World Cup, and was dogged by a grievance about the days other qualifying match. The gripe erupted again after the landing at Rome airport.

The privileges of political office had been snatched by the chancellors party. On the instructions of Sir Thomas Richardson, the British ambassador, the embassys economic secretary, Rob Fenn, welcomed the group at the airport. But rather than drive direct to the embassy, Brown asked Fenn whether he knew anyone in Rome who subscribed to Channel 5. Ive got to see the Scotland Latvia match, he said. After frantic telephone calls, Peter Waterworth, a first secretary, was unearthed. His mother gave him a Sky subscription for his birthday, reported Fenn with relief. Channel 5 comes with the card. Well done, gushed Brown. Robinson beamed. A brief diplomatic chore over lunchtime had been arranged with Carlo Azeglio Chamoi, the Italian finance minister, to justify the trip. After that, the pleasure could start.

Latvia, we love you, chanted a group of England fans, spotting Brown step from the ambassadors car in the centre of Rome. Brown smiled back. Public recognition elated the congenitally clandestine bachelor. Footballs tribalism was a bond, and he assumed that Waterworth, a Manchester United fan from Belfast, would welcome a Scottish fan in his living room. Hello, Im Gordon Brown, smiled the chancellor as Cathy Waterworth opened the door. Im so grateful that youll have us, he said, leading thirteen people into the flat before his putative hosts could have second thoughts. Geoffrey Robinson immediately assumed the role of waiter, ferrying bottles of Peroni beer from the fridge at the far end of the flat to the chancellor, already hunched up close to the television, revealing the handicap of his single eye. Preoccupied, Brown uttered only a few comments throughout the match. At half-time he disappeared to be interviewed by a journalist for Mondays newspaper. Robinson used the opportunity to look at Waterworths oil paintings. My fathers the artist, explained the host. Would you sell me that one? asked the paymaster general. The doorbell rang. A journalist returned with a bunch of flowers for Cathy. When the second half started, Robinson resumed his duties as waiter, and as Scotlands 20 victory seemed assured, the atmosphere became light-hearted. Great, announced Brown at the end. After more jokes, he bade farewell. He looked forward to the live match later that night.

The next stop was the British embassy. I wonder how much wed get if we flogged this lot, chortled Whelan in his south London accent as they walked into the marbled, ornately furnished building. The chancellor smiled at the joke directed at Robin Cook, the foreign secretary, one of Labours tribe whom Brown, during his fraught journey up the partys hierarchy, had grown to loathe. They were joined by Stuart Higgins, the editor of the Sun, Tony Banks, the minister for sport, and Jack Cunningham, the minister of agriculture. Neither of the politicians was a Brownite, and their politeness towards the chancellor was noticeably diplomatic. Standing in the corner was Sir Nigel Wicks, the Treasurys second permanent secretary. Are you going to the match? Wicks was asked. No, he replied hesitantly. Why? Prudence. What? Im here on business, and I would not want my presence in Rome to be misinterpreted. The Treasury, some speculated, had contrived the visit to the Italian finance minister as a fig leaf to justify the junket. The final guest, the genial former Manchester United star Bobby Charlton, was uniquely guaranteed Browns affection.

Next page