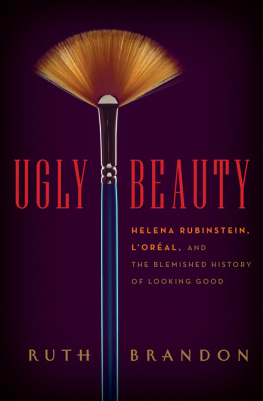

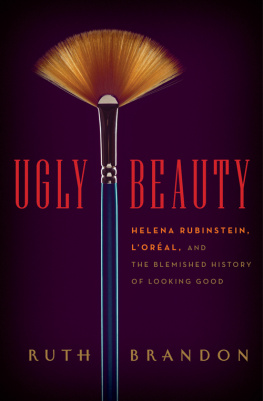

Ugly Beauty

Helena Rubinstein, LOral, and the Blemished History of Looking Good

Ruth Brandon

Dedication

To my unretouched female friends

Contents

E veryone has heard of Helena Rubinstein, international queen of cosmetics. Tiny, plump, spike-heeled, bowler hatted, and extravagantly jeweled, she was for many years one of the fixtures of the New York scene, scurrying between her vast apartment on Park Avenue and her salon on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-seventh Street, in one hand an enormous leather bag stuffed with cash, business notes, old tissues, and spare earrings, in the other a paper sack containing a copious lunch. Instantly recognizable to all from the photographs that adorned her advertisements, she was energy personified, at once comic and awe inspiring.

Few, by contrast, have heard of Eugne Schuellerthough everyone knows LOral, the firm he founded in Paris in 1909. Like Rubinstein he was born poor; like her, he rode to riches on the back of womens compulsion to beautify themselves. Unlike her, however, neither his name nor his face were familiar to those who bought his hair dyes. Immured within his empire, traveling between factories in the Rolls that was his office on wheels, he shunned personal publicity. So removed was he from society, indeed, that when his wife died and he wished to remarry, the only woman he could find, though he was by then one of the richest men in France, was his daughters governess.

In 1988, Schuellers business swallowed Rubinsteins. In the normal way of things the takeover would have gone unnoticed except in the business press. But Rubinstein was a Jew, while Schueller, during the German Occupation, had been a leading fascist collaborator. And although they never met during their lifetimes, and both, by then, were long dead, the consequences of this potentially lethal opposition outlived them. The conjunction led to a series of scandals that not only threw a new and sinister light on LOral but threatened the reputations of some of Frances most powerful menup to and including its president himself.

It may seem oddcertainly unexpectedthat a history of the beauty business should include an excursion into fascist politics. But cosmetics, unlike clothes, have always been a political hot potato. The stories of Helena Rubinstein and Eugne Schueller show us why this has been soand continues to be so today.

Beauty Is Power!

I

H er life,said Vogue of Helena Rubinstein, reads like a fairystory. It was 1915: Madame (as she wasalways known) had just opened her first New York salon. Dark-blue velvet coveredthe walls of its main room, with rose-colored woodwork and sculptures by ElieNadelman from Madames own art collection. Each of the many other rooms had itsown decorative theme, from a Louis XVI salon to a Chinese fantasy in black andgold and scarlet. The diminutive proprietor, high heels adding a few neededinches to the mere four foot ten nature had allowed her, personally showed thejournalists around. However busy she might be, there was always time forjournalists. Madame, ever keen to pinch a penny where she could, knew no amountof advertising could equal the boost afforded by a really long interview, withphotos, spread over several pages. And such a piece cost nothing at all.

The fairy story in question was a classicrags-to-riches tale. Twelve years earlier, in 1903, Helena Rubinstein, a pooremigrant from Poland, had opened her first beauty salon: a single room inMelbourne, Australia, from which she sold pots of homemade face cream. So greatwere her marketing skills, such the demand, and so enormous the markup, thatwithin two years she was rich. By 1915 she was a millionaire. She had dazzledLondon and Paris, and was set to do the same in America.

Fairy stories, however, are more than just dazzlingsocial leaps. They are also dramatizations of our deepest dreams. And in thissense, too, the metaphor was apposite, both for Rubinstein and for her chosenindustry. For cosmetics are all about dreamsspecifically, the dream of anideal, time-defying physical self.

Generally speaking, the public acceptance ofwomens cosmetics has varied according to the social status of their sex. Whenthe Roman poet Ovid, in his Ars amatoria , advisedwomen to make sure their armpits didnt smell, that their legs were shaved, tokeep their teeth white, to acquire whiteness with a layer of powder, to rougeif they were naturally pale, hide your natural cheeks with little patches, andhighlight your eyes with thinned ashes, he was speaking to a society wherewomen had substantial social freedoms in all spheres other than politics.Equally, the heroine of Popes Rape of the Lock ,with its famous dressing-table scene enumerating Puffs, Powders, Patches,Bibles, Billet-doux, was free to take her place as an active player on thesocial stage. But in societies where a wifes functions are solely to producechildren and service her husband, cosmetics are taboo. Saint Paul inveighsagainst them; the Talmud declares that a beautiful wifebeautiful withoutcosmeticsdoubles the days of her husband and increases his mentalcomfort.

The nineteenth century, particularly in Britain,was just such a society: in the words of social commentator William RathboneGreg, writing in 1862, a womans function in it was to complete, sweeten, andembellish the existence of others. But HelenaRubinsteins good fortune, after a century of repression during which norespectable lady could allow herself even a touch of rouge, was to hit a momentwhen women were poised to claim new freedoms. Her fairy-tale richesrubies,emeralds, pearls, and diamonds that would not have looked out of place in AliBabas cave, sculptures and paintings, apartments and houses in New York,London, Paris, and the Rivierareflected, in the reassuringly solid form Madamealways favored, this surge of empowerment. And since empowerment is the keynote,too, of her own personal story, nothing could be more appropriate than that thefirst woman tycoonthe first self-made female millionaireshould have amassedher fortune through cosmetics.

Rubinsteins life, as recounted by herself in twomemoirs, was a fairy tale in yet another sense: a desirable fiction that hadlittle to do with reality. I have always felt a woman has the right to treatthe subject of her age with ambiguity until, perhaps, she passes into the realmof over ninety, she wroteshe herself being, by then, well into that realm. Andambiguous she was, and remained, not just about her age but about every aspectof her life. Although in the year of her death she finally acknowledged she wasborn in the early 1870s, on Christmas Day (the year was in fact 1872), eventhen she maintained the storyrepeated so often she had perhaps come to believeitthat the family had been well-off. They lived, she said, in a big house nearthe Rynek, the ancient and splendid market square that is Krakows city center;her father, a wholesale food broker, was an intellectual who collected booksand fine furniture; she herself had attended a gymnasium, she had for two yearsbeen a medical student, and her sisters, too, had attended university.

In fact anyone could tell that Helena had beenpoor, and hated it, from the extreme pleasure she took in being rich, piling upthe bright, shiny goodies with a compulsive delight that never dimmed and thatno one born rich could ever experience.

Similarly, it is clear she would have studiedmedicine if she could. She always projected herself as a qualified scientificprofessional, was constantly photographed in white lab coats amid test tubes andBunsen burners, emphasized her productsquasi-medical aspects. She became asknowledgeable in her field as anyone alive. But that field was far fromscientific, and such knowledge as she possessed was laboriously gleaned over theyears, not formally acquired.

Next page