Table of Contents

We must be aware of the dangers which lie in our most generous wishes. Some paradox of our nature leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the objects of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then of our wisdom, ultimately of our coercion.

LIONEL TRILLING

Im eighty years old, and after thirty-two years in the fire department, I can say there isnt anything as exciting as responding to a fire. Nothing. Nothing I have experienced or read about as exciting as getting on that truck with lights blazing, sirens going, then turning the corner and seeing the red demon coming out of that building. Its a strange group of men, and I was proud to be one of them. If sociologists and psychologists would have studied us, they would have been shocked at what they found.... No one runs into a building that everyone else is running out of without one or two screws loose, constantly facing death and danger like that, but its what we did. They call it the War Years, but I also call it the Glory Days.

RETIRED FDNY CAPTAIN VINCENT JULIUS

A NOTE ON SOURCING AND PHRASING

All dialogue in this book is from the memory of the participants, and has been checked with multiple sources wherever possible. To distinguish between the sources, quotations taken directly from interviews conducted by the author are referred to in the present tense (... says) and those taken from books, articles, or archives are quoted in the past tense (... said). Because the events described take place before women joined the FDNY, firefighters are generally referred to as firemen.

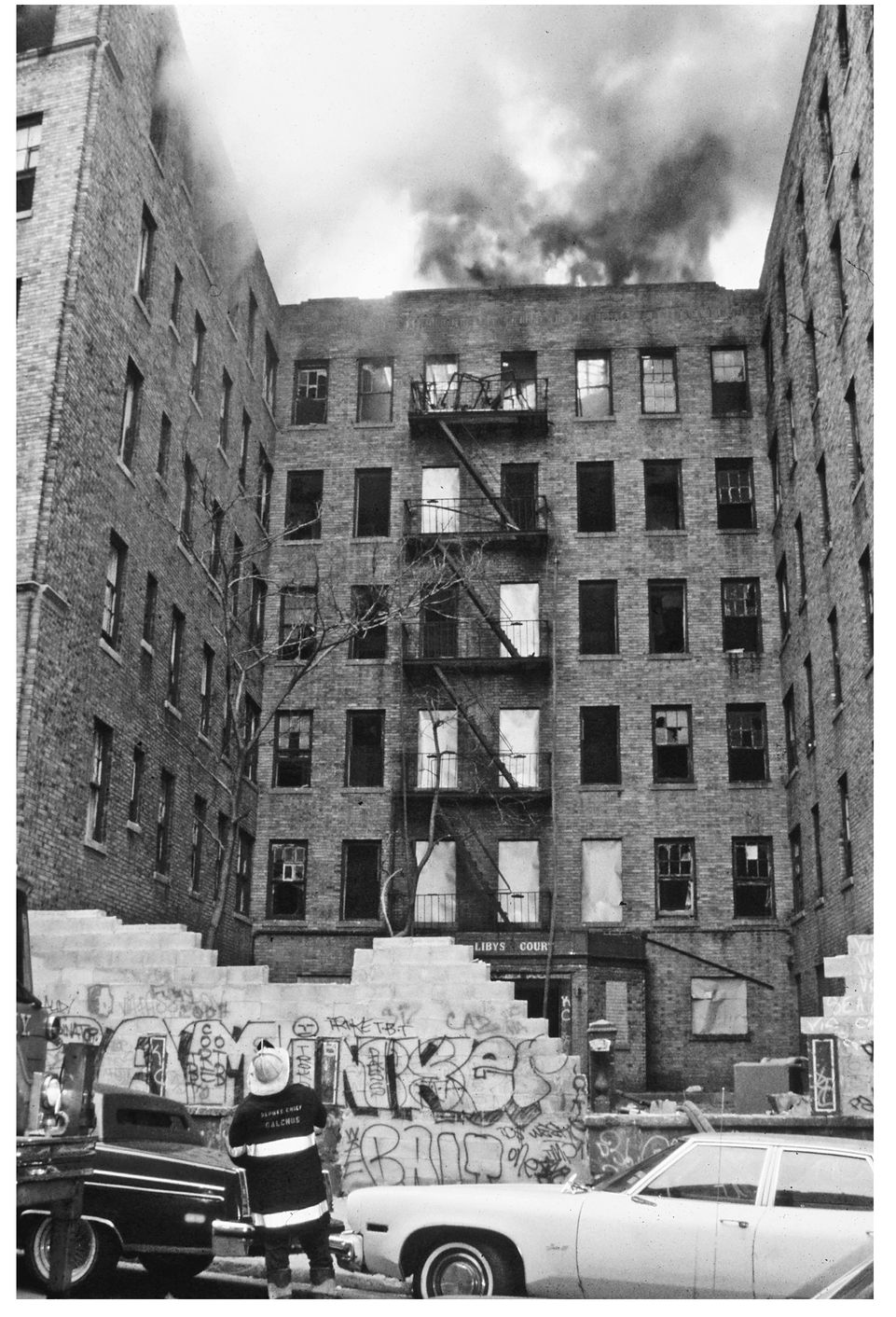

The Waldbaums collapse, Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. (Photo courtesy FDNY Photo Unit)

ONE

The War Years

We cannot understand firemen; they have risen to some place among the inexplicable beauties of life.

MURRAY KEMPTON, New York Post, AUGUST 3, 1978

Just after eight-thirty in the morning on August 2, 1978, a small fire broke out on the mezzanine level of a busy Waldbaums supermarket in the Sheepshead Bay neighborhood of southern Brooklyn. I saw flames coming from a large wooden beam right next to the mens room wall, said plumber Arthur Stanley, who was part of a construction crew adding an extension to the mezzanine. I told somebody to tell the store manager and then I hooked up this garden hose I keep in my tool kit, and tried to put it out. Store managers delayed calling the fire department and evacuating customers from the market, but when the flames spread to a storage room they relented, and employees had to convince reluctant customers to leave their carts and exit the store. At 8:39, the call came in to the fire department, and within three minutes the first fire engine was on the scene. The units at the scene quickly radioed for backup, and after an eight-minute delay, dispatchers complied, calling a second alarm just after nine oclock, and a third and a fourth alarm soon after that.

Across the street from the fire, Louise OConnor stood with her three childrenfive-year-old Billy Jr. and his little sisters, Lisa Ann and Jean Marie. A few minutes earlier, Louise had arrived at Brooklyn Ladder Company 156 to pick up her husband, Billy OConnor, after the nine a.m. shift change, but saw that the houses garage was open and empty. One of her husbands friends from the house saw her waiting outside and told her Billy was out at a fire. It was contained, hed said, nothing to worry about, and gave her directions. When she reached the supermarket, the blaze was far from out. Waves of heat radiated from the building, and thick clots of dusky smoke oozed into the sky. A dozen or so engines and ladder trucks idled in the parking lot, and the arm of a big tower ladder was telescoped out over the roof of the building. Standing across the street from the fire, Louise was distracting the kids to keep them calmpointing out things to look at, explaining what was going onwhen she spotted a familiar frame striding out the front door of the Waldbaums.

Were standing in front of the building, and Im watching and Im watching, says Louise, and now we see Billy come out of the building, and the kids are calling him but he doesnt hear. Then he went up the ladder and onto the roof and I guess he must have heard the kids or maybe he justI dont know, he turned around and they were yelling and waving and he waved and he stepped on the roof.

Just as Billy walked out of sight, a sudden flash shone through the windows of the market and the roof hemorrhaged thick streams of jet-black smoke. A security guard standing next to Louise told her it was nothing the firemen couldnt handle, but she had a bad feeling. A fresh wave of heat rippled from the building and Louisemuttering God, Christ the fire, to herself over and overtook the kids across the street to a pay phone to call Billys father, a captain in a nearby Brooklyn firehouse.

STANDING ON THE ROOF OR FLOOR ABOVE A BLAZE IS THE most dangerous place a fireman can position himself. Before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the deadliest day in the history of the Fire Department of New York came when the first floor of a brownstone apartment building collapsed into a burning basement below, killing twelve firemen. Most of the deadliest blazes for American firefighterstwenty-one killed in a Chicago stockyard in 1910; fourteen in a Philadelphia factory that same year; thirteen killed in a Massachusetts theater in 1941were all collapses. But getting above the fire is precisely what the truckies of a ladder company like Billy OConnors do for a living. Engine companies put water on a fire. Along with rescues, a ladder crews job is to vent the heat and smoke from the blaze. Without venting, fire crews run the risk of a backdraft, when an oxygen-starved fire gets a sudden burst of airsay from another fireman, axing his way through the doorand the fire explodes outward. More often, the heat and smoke from a blaze radiate back into the room to cause a rollover, when carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons smolder in dancing blue flames that roll along the ceiling like northern lights in the winter sky. In the engine of a car, the exploding gasoline isnt hot enough to burn off these gases, so a catalytic converter is used to change their chemical structure to burn at lower temperatures. In a rollover, there is no chemical catalyst, just heat blasting the molecules apart. Without venting, a rollover can quickly turn into flashover, when everything in the room is heated to the point of ignition and suddenly bursts into flames.

The easiest way to vent a fire is to break out windows and doors, but the most effective method is to tear holes in the roof or ceiling above the blaze. Truckies have a few tricks for spotting and preventing collapses. Once theyre actually above a fire, they look for sudden puffs of smoke coming up through the vents, and check the roof theyre standing on for increased warmth or softness. But the most important work happens before ladder crews even set foot on a roof, when they scout the fire from below. Some of their methods are by-the-book: checking the severity of the fire, cutting small holes in the ceiling and walls to see how far it has spread, studying the buildings construction for weaknesses. Others are harder to quantify, the almost subconscious process of stacking up the countless, tiny details gleaned from the blaze at handthe smell, shifts in air currents and pressureand comparing them with the accumulated wisdom of a career spent fighting fires. It all happens so quickly that most firefighters describe it as little more than a gut feeling, but, like hitting a curveball or making a no-look pass, its a matter of skill and experience, not divine inspiration.