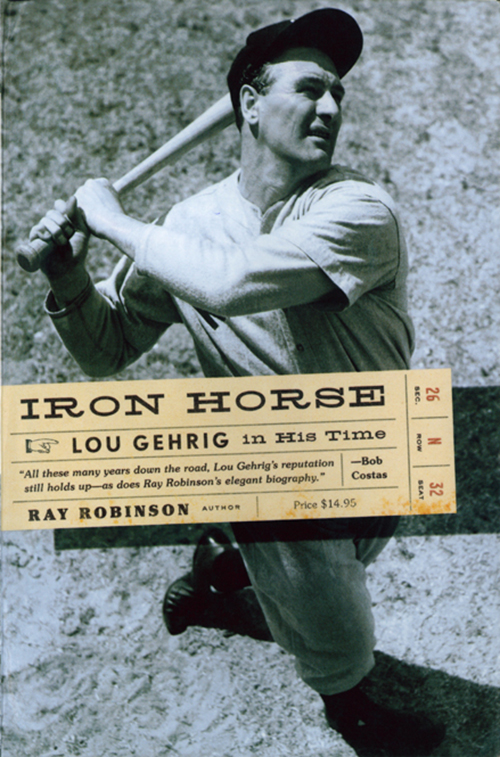

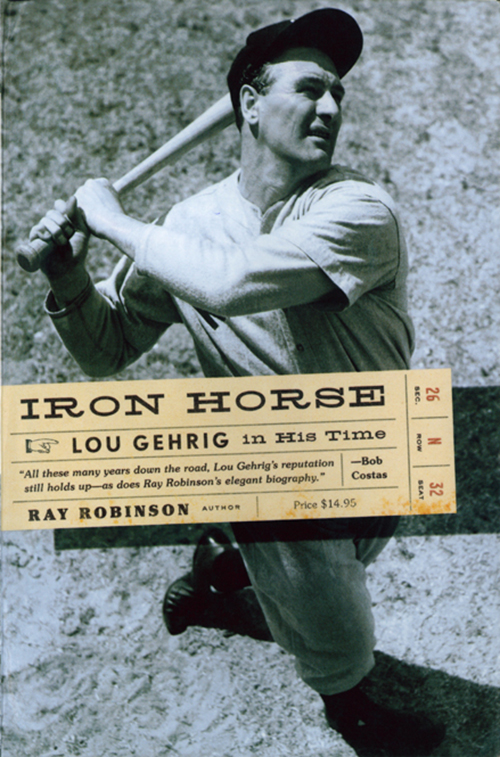

Praise for Iron Horse

Anyone who ever saw Lou Gehrig in pinstripes will always remember his awkward grace, his image of raw power. It is fifty years since Gehrig was a Yankee, and Ray Robinson, thank goodness, has captured his unique personality so vividly that a new generation can finally learn why their fathers and their grandfathers say that Lou was the greatest first baseman who ever lived.

Lawrence Ritter, author of The Glory of Their Times

Gehrigs is one helluva story.

Sports Illustrated

Ray Robinson has hit a bases-loaded home run. His authoritative biography of Lou Gehrig picks up where Frank Grahams classic A Quiet Hero left off and fills a long-lasting need in baseball writing.

Robert Creamer, author of Babe: The Legend Comes to Life

A lovely book.

Red Barber

Ray Robinsons compelling new biography of Lou Gehrig fills a large gap in baseball literature. Here at last, told with warmth and candor, is the story of the man behind the monument.

Donald Honig, author of Mays, Mantle and Snider

Just as Lou Gehrigs glove and bat were hard to put down during his remarkable consecutive game streak, so it is hard to put down this terrific new biography of the Iron Horse. Baseball fans should love reading every page of it!

Tim McCarver

Not only reintroduces a sports legend but... reminds everybody the game hasnt changed... that much.

George Vecsey, New York Times.

IN THIS CAREFULLY RESEARCHED BOOK , RAY ROBINSON TURNS AN AMERICAN ICON INTO A LIVING, BREATHING HUMAN BEING. IN DOING SO, HE ALSO TELLS A MARVELOUS STORY OF A MAN AND HIS TIMES.

PETE HAMILL

Also by Ray Robinson

Greats of the Game

American Original: A Life of Will Rogers

Oh, Baby, I Love It! (with Tim McCarver),

The Mario Lanza Story (with Constantine Callinicos)

Ted Williams

Stan Musial

Baseballs Most Colorful Managers

Greatest Yankees of Them All

Greatest World Series Thrillers

IRON HORSE

Lou Gehrig in His Time

RAY ROBINSON

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

Some images in this e-book are not displayed owing to permissions issues.

Copyright 1990 by Ray Robinson

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2006

Lines from You Cant Go Home Again by Thomas Wolfe. Copyright 1934, 1937,

1938, 1940 by Maxwell Perkins as the Executor of the Estate of Thomas Wolfe.

Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

Book design by Jacques Chazaud

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Robinson, Ray, 1920 Dec. 4

Iron horse: Lou Gehrig in his time / Ray Robinson.

p.cdm.

1. Gehrig, Lou, 1903-1941.2. Baseball playersUnited States

Biography. 3. New York Yankees (Baseball team) I. Title.

GV865.G4R63 1990

796.357092dc20

[B]

89-29272

ISBN-13: 978-0-393-32882-0 (paperback)

ISBN-10: 0-393-32882-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-393-24725-1 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3QT

For Tyler

In the early 1930s, when Lou Gehrig was in the midst of his remarkable consecutive-game streak, I was in my pre-teen years, a worshipper and celebrant from afar. I suspect there were many other youngsters, not necessarily New York kids, who were also captivated by his achievements.

True, he was not baseballs dominant personality in that era, for it was Babe Ruth, as implausible a sports figure as was ever born, who occupied that role. But through all the years of Yankee hegemony I preferred Gehrig, even as he played and lived constantly in the bulging shadow of Ruth.

In popular parlance, Gehrig was the designated crown prince to Ruths kingship. Ruth, the incomparable Bambino, was everybodys Sultan of Swat, even to those who had only a modest interest in the national pastime.

If everybody loved the Babe and recognized his homely features on sight, I was more taken with Gehrigs diffidence, his dimpled smile, his surface calm, his unmistakable Boy Scout aura. If Gehrig was destined to play second banana to the larger-than-life Zeus who preceded him in the batting order of the Yankees Murderers Row, I still chose Gehrig over the Babe. I wanted my heroes to be less flamboyant than Ruth, less outrageous, less self-centered, preferring the stubborn day-by-day dedication of Gehrig.

While the Babe connected for higher-than-heaven home runs, Gehrig settled for screaming line drives. Even when the Babe minced across the street, on those celery-stick legs, he won cheers. When he struck out, as he often did, it was with the panache of a Shakespearean actor, and he was applauded to the echo as his bat lashed the air unmercifully. Who ever heard of a baseball player striking out to the accompaniment of cheers! Did they cheer for Lou when he went down on strikes?

When Ruth winked or when he croaked his familiar Hi, keed to friends and strangers alike (names of teammates seemed to escape him), he was adored on the spot. When Gehrig signed his autograph in a neat script that fit his personality, he won only modest approval.

While Ruth hit 259 of his homers in Yankee Stadium, of a lifetime accumulation of 714, Gehrig hit 30 Stadium homers in 1930, the most ever hit in one year in that park, until Roger Maris hit 30 in 1961.

But despite Lous productivity at the Stadium, the right-field bleachers, where many of Gehrigs blasts nestled, were named after the Babe. The section was popularly referred to as Ruthville. Nobody ever heard of anything called Gehrig Gardens.

Gehrig was the guy who hit all those home runs the year [1927] that Ruth broke the record, wickedly wrote columnist Franklin P. Adams. Always it was the Gargantuan silhouette of Babe intruding on Lou. Even after Babe bowed to the years, others took the spotlight from Lou. When Gehrig experienced his four-home-run game in Philadelphia, the headlines were devoted instead to the retirement of John J. McGraw. Still later it was Joe DiMaggio, exuding a remarkable sense of class and grace, who managed to look better in Yankee pinstripes than Lou.

In Gehrigs time ball players were encumbered in heavy, sweaty wool uniforms that were about as chic as old bloomers hanging on clotheslines. Suited up, Gehrig looked bovine, unath-letic. His appearance earned him the uncomely nickname of Biscuit Pants. But shouldnt one win points for modesty, decency, and determination? I thought so, and of all the Yankees, it was Lou I cherished the most.

There was something else. Gehrig had enrolled in 1921 at Columbia, a school that also produced Eddie Collins, the Hall of Fame second baseman who maintained his pristine reputation even through the Black Sox scandal. My father attended Columbia when Collins was there and, though he wasnt much of a baseball fan, he understood the greatness of Collins. His pride in Columbia caused him to nurse special feelings for Gehrig, too. Hed often leave his law office in the Woolworth Building early on spring afternoons, so he could watch Gehrig play on Columbias South Field.

Lou used to hit tremendous fly balls off the steps of Low Library and off the walls of the Journalism Building, my father informed me. He judged such blows could have traveled 500 feet from home plate, on the Amsterdam Avenue side of South Field. There was another story he told that had Gehrig bouncing a baseball off the white-haired head of Columbias dean, Herbert Hawkes, as that gentleman took a stroll some 150 yards away.

Next page