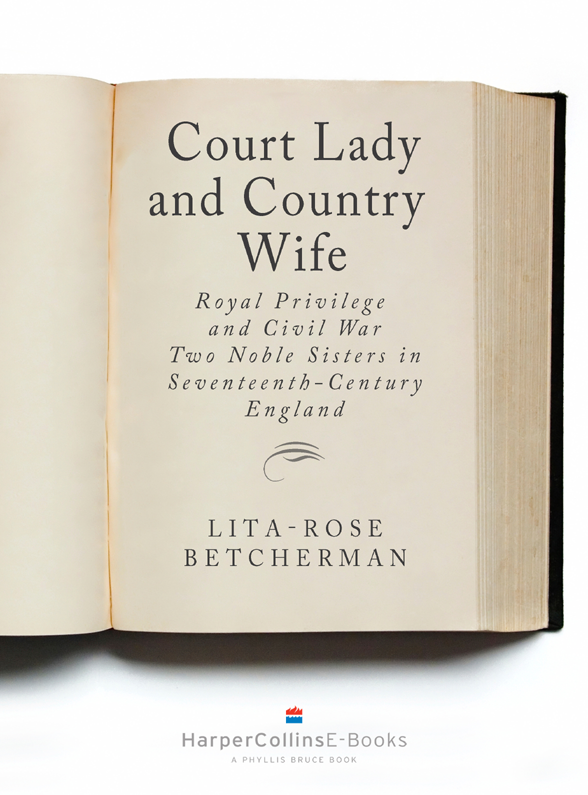

COURT LADY

COUNTRY WIFE

Royal Privilege and Civil War:

Two Noble Sisters in

Seventeenth-Century England

LITA-ROSE BETCHERMAN

Contents

ON A RAINY FEBRUARY DAY in 1617, a barge drew up to Tower Wharf on the River Thames and two young women disembarked. From their dress and from the barge bearing a coat of arms, it was obvious that these young women were members of the nobility Dismissing the oarsmen, they crossed the drawbridge over the moat and entered the confines of the Tower of London as the great iron gates clanged shut behind them. Escorted by a pair of oafish guards, they circled the inner wall, carefully averting their eyes from Tower Hill, where their uncle not so many years before had been beheaded, and continued on to the Martin Tower in the northeast corner of the bastion wall. Dorothy and Lucy Percy had come to visit their father.

Henry Percy, ninth Earl of Northumberland, had been a prisoner in the Tower during the years when the sisters were growing up. In 1606 he had been found guilty of complicity in the failed Gunpowder Plot to blow up Westminster Hall at the very moment King James I, having ascended to the throne just three years earlier, was opening Parliament. The case against the Earl had, in fact, never been proven. His conviction rested on guilt by association; during the investigation it came out that the day before the plot was discovered, one of the chief plotters, a distant relative employed by the Earl to collect the rents from his northern estates, had dropped in on him at his country house. Whether guilty or not, the ninth earl was following in the family tradition. His grandfather Sir Thomas Percy had been attainted and executed for his part in the revolt against Henry VIII, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. His uncle, the seventh earl, had been beheaded in the Tower for treason, and his father, the eighth earl, committed suicide when he was sent to the Tower a third time for plotting against Queen Elizabeth I.

Yet the room the sisters entered was no dank prison cell. It was the withdrawing room in a suite of six luxuriously furnished rooms. The Earl had brought the finest tables, chairs, and chests from his castles throughout England. The stone walls were hung with tapestries, and Turkey carpets warmed the floors. Even in prison the Earl remained a great noble, living in style as if the Tower were his private castle. Through well-placed bribes, particularly to the Lieutenant of the Tower, he had appropriated the Martin Tower for himself and converted it into this comfortable habitation. As well, he had set up a laboratory for his scientific experiments. Several of his protgs mathematicians and astronomersstayed with him in the Tower, and he kept twenty servants, renting a house on Tower Hill for the overflow. With the cooperation of the Lieutenant of the Tower, he acquired the use of Tower grounds for a bowling alley, an archery range, and stables for his horses, which were regularly exercised by his Master of the Horse.

An irritable and overbearing man, Northumberland was as arrogant in prison as out. When a fellow prisoner wandered onto the gravel path where he took his daily walks, he beat the unfortunate interloper with his cane. It was said of the Earl of Northumberland that were it not for the blot on his escutcheon, he would have been perfectly content with his incarceration.

If the Earl had paid attention to his pretty daughters on this particular visit in 1617, he might have noticed that they were somewhat subdued. Dorothy was always reserved, but Lucy, the younger sister, was ebullient by nature. This day her contagious laughter was not to he heard by the guards and prisoners. The truth was that the sisters had come with news they knew would make their father exceedingly angry. They had decided their future on their own, in defiance of his plans for them. Each in her own way was looking forward to living happily ever after with a wealthy, well-placed husband. But in their youthful self-confidence, they could not know all that the future held for them or for England itself. As fate would have it, one of them would also end up in the Tower of London and in very different circumstances from those of their father.

MONEY

AND

MARRIAGE

one

TWO PRETTY SISTERS

DOROTHY WAS SEVEN and Lucy six when their father, Henry Percy, ninth Earl of Northumberland, was sent to the Tower. On November 4, 1605, he set out by water from Syon House, his country home on the banks of the Thames just west of London, to attend the opening of Parliament the following day Six months later he was found guilty of treason. It would be sixteen years before he returned.

The sisters lives, however, hardly changed as a result of their fathers imprisonment. Like all children of the nobility, they saw little enough of their mother and even less of their father. Theirs was a world of nurses and maids, grooms and gardeners. In truth, they were better acquainted with the seventy blue-liveried servants at Syon than they were with their father. Nor was the Earl a fond parent to be missed. When he came upon them at play, he would not stop to talk: the conversation of children is unsuitable to my humour, he was wont to say For their part, the sisters shed few tears at his absence. With their father gone they no longer had to listen to their parents squabbles. How it had made their hearts pound to hear their hot-tempered mother shouting at their father and his cold, low-spoken replies goading her into wild sobbing.

The little girls would have had no recollection of it, but their parents had separated when Lucy was an infant and Dorothy just a toddler. In October 1599, the Countess left her husband. Her side of the story was that the Earl had thrown her out for no reason: It was his Lordships pleasure upon no cause given by me to have me keep house by myself, she wrote her brother, Essex. It may have been no coincidence that at this very time the Earl of Essex, formerly Queen Elizabeths pampered favorite, was under house arrest for disobeying the Queen. The ambitious Northumberland had married the sister, Dorothy Devereux, because of the brother: a family connection with the fallen favorite now was politically unwise.

Forced to live on her own, Lady Northumberland rented a modest house in Putney, leaving the baby girls with their father. It was not that she did not love her daughters; she simply did not have the wherewithal to provide for them in a manner suitable to an earls children. Because the land and goods she had brought into the marriage had automatically become her husbands property, she was left with a very small allowance. Nevertheless, several months later when she heard that her daughters were not thriving, she insisted that they live with her. Perhaps Lucy was rejecting the wet nurses milk, or perhaps the two-year-old was pining away Lord Northumberland allowed the girls to go to their mother but provided no increase in her allowance to care for them.