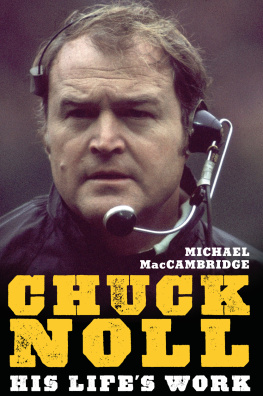

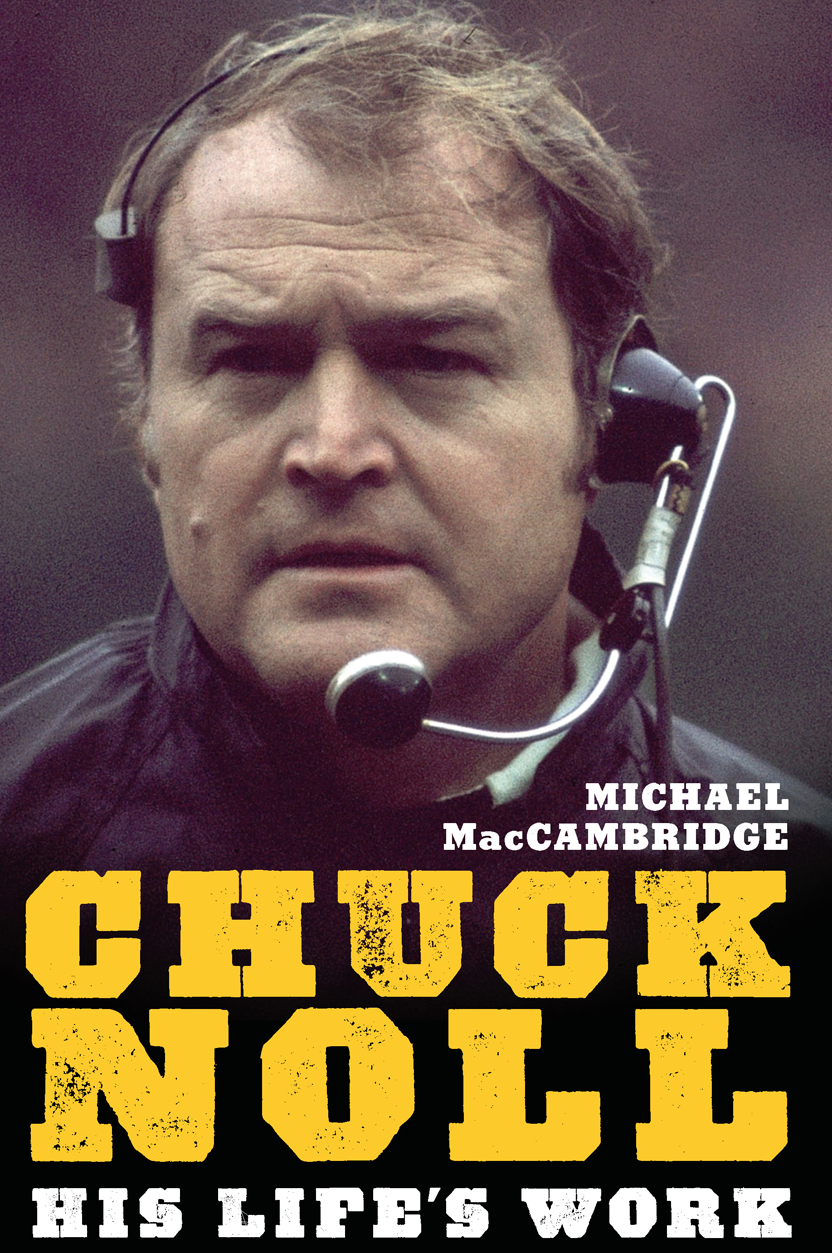

Cover design by Joel W. Coggins

Cover photo by Walter Iooss Jr. / Sports Illustrated / Getty Images

And in a world we understood early to be characterized by venality and doubt and paralyzing ambiguities, he suggested another world, one which may or may not have existed ever but in any case existed no more: a place where a man could move free, could make his own code and live by it; a world in which, if a man did what he had to do, he could one day take the girl and go riding through the draw and find himself home free.

PROLOGUE

From the sidelines, through the maze of bodies, he could see it developingthe initial misdirection, Harris taking a step to his left, turning completely around and now heading right; Mullins setting back in a pass-blocking stance, then releasing to lead interference; Harris accepting the ball from Bradshaw and sliding into the vacated outside hole, beginning to rumble as his blockers cleared the way. By the time the exhausted Vikings, defenders dragged him down, hed gained 15 yards, the Steelers had another first down, and the final result was no longer remotely in doubt.

As the lights cast an ethereal glow through the frigid gloom of the New Orleans twilight, and the scoreboard clock worked its way toward :00 in the heavy Louisiana air, Super Bowl IX neared its conclusion, and the Pittsburgh Steelers stood on the verge of becoming world champions. The seasons work was nearly complete.

It was in these moments, with the end of the quest imminent, when Chuck Noll often would feel the emptiest.

All the shared effort and focus that Noll had mustered throughout the long season was bound up in that moment and then, after the inevitable diminution of time, it was all over. He was left then with nothing but the formalitiesthe handshakes and mere words that could never do justice to the things he felt. For a time, he held the melancholy and hollowness at bay, in the negative space where the sense of purpose had thrived for months. It all remained on the inside, where he kept his deepest feelingsunshared, unremarked upon, often unexamined.

On the outside, where his football players were whooping and hollering, there was only a sublime, sincere expression of joy in that moment of complete triumph. Noll often seemed impervious to these common sentiments, but in this case he too was swept up in the tide, grinning as his players hoisted him on their shoulders.

Yet even in this instant of complete victory, the head coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers enjoyed but did not exult. Five years earlier in the same stadium, Hank Stram had triumphantly waved the rolled-up sheets of his game plan while being carried off the field by his Chiefs; two years earlier, following Super Bowl VII in Los Angeles, Don Shula had rejoiced on the shoulders of his Miami Dolphins, raising a pair of fists skyward at the completion of a perfect season.

But on January 12, 1975, there would be no such indelible image. Noll, ever the pragmatist, simply used his arms to steady himself on the shoulders of Franco Harris and the helmetless, beaming Joe Greene as they carried him across the field on his brief victory ride. He appeared delighted but composed, keenly aware that the trip he was taking was a fleeting one.

He was back on his feet by the time they reached the tunnel, heading to the bowels of the decrepit Tulane Stadium. Inside the visitors dressing room, with its long wooden benches and low-slung ceilings, there was a cacophony of noise and sweat and deadline journalism, with a mob of cameramen, reporters, league executives, team employees, and interlopers standing amid the oversized men reveling in the greatest moment of their sporting lives.

In sports, all championships carry an air of redemption. But this one went beyond that. More than forty years after theyd entered the league, the Steelers had finally won their first NFL title. There was a deep, primal release from decades of frustration for the city of Pittsburgh and theteam. Players were crying tears of joy, coaches were hugging, others in the room were shouting exhortations.

In the midst of all that revelry, Chuck Noll, the head coach of the Steelers, did none of those things. He smiled, exchanged congratulations, and shook hands.

Grasping Terry Bradshaws hand, he said, Congratulations, we did it.

Congratulations, Andy, he told the veteran linebacker Andy Russell, shaking his hand. This is why we do the hard work.

Then he shook Frenchy Fuquas hand, and said, Congratulations, we did it.

NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle entered, and then everyone in the room focused on the owner and team patriarch, the white-haired Art Rooney, The Chief, he of the thick glasses, jaunty Ascot, and outsized cigars. It was only after Rozelle presented the Lombardi Trophy to Rooney, and after Franco Harris was awarded the games most valuable player award, that Noll was cornered in the locker room by NBC broadcaster Charlie Jones and asked on national television about his thoughts on the occasion of finally attaining the greatest goal in professional football. How, asked Jones, were Noll and his players going to celebrate this achievement?

I think were going to enjoy it for just a short time, and then get on to next year.

It took Jones another instant to realize that Nolls brief answer was complete.

And then be ready for next season... already?, Jones prompted.

Thats right, it comes around fast.

Even thenperhaps most especially thenChuck Noll was cognizant that success was not a fixed point but an ongoing state of mind, a series of habits and commitments. Hed made a life out of setting them and honoring them. He wouldnt stop now.

More than two hours later, after hed extended dozens more congratulations to players and staff, and faced the gauntlet of television, radio and print interviews, he made his way back to his suite at the Fontainebleau Hotel.

His wife Marianne, wearing her lucky Steelers bracelet, had been sitting on the sofa, still reveling in the thrillthinking about how much it meant to Chuck, the assistants and the players, and how this game wouldchange all of their liveswhen she heard the key in the door. She stood up, beaming broadly and held her arms out as he walked in the room.

And as he approached her, he extended his right hand, shook hers firmly and said, Congratulations. We did it.

Years later, Nolls detractors would cite this scenea coach celebrating the culmination of his greatest victory by offering a perfunctory, congratulatory handshake to his own wifeas proof of his bloodless personality and his inability to relate to the people nearest to him.

And, just as forcefully, Marianne Noll would maintain that the proffered handshake from her soul mate was just one more inside jokeWe both were laughing at the time, she saidas well as further proof, perhaps, that you had to know Chuck.

Then again, perhaps no one else did.

Vince Lombardis name is on the Super Bowl trophy that is presented to the National Football League champion each year, and he remains the standard by which all football coaches are judged.