For Glenn & Greg,

big brothers,

consummate teammates

What has the game given me? Its given me my teammates.... You want to talk about what the game takes away from you? It takes away your teammates.

John Banaszak, Pittsburgh Steelers (19751981)

I

INTRODUCTION

REVERIE & REALITY

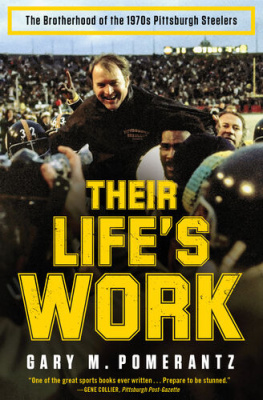

BECAUSE WE SEE SPORTS DYNASTIES through the prism of stopped time, the players never grow old. We forever see the 1970s Pittsburgh Steelers in their days of empireBradshaw airing it out, Mean Joe enraged, Lambert toothless, stamping his feet before the snap, the long, elegant strides of Stallworth, Franco, still immaculate. But time does not stop, not for us, not for the Steelers of the 1970s.

Have a cigar, mboy! Sitting in his living room near Dallas, wearing slippers, Mean Joe Greene remembers Art Rooney Sr. He hears the old mans voice with its smokers rasp. He shared conversations with the Chief at the Rooney home on Pittsburghs North Side at 940 North Lincoln Avenue. They sat in the den beside the fireplace. Through the front windows, they saw moonlight play on Three Rivers Stadium. The Chief sat in his favorite black leather recliner (it vibrated), a brass spittoon at his feet, his TV turned to local news or an old Western (the volume too loud); on a nearby table he kept his rosary beads.

Such a compelling pair, the Chief and Mean Joe: the Pittsburgh Steelers founding owner was an old horse player with a map-of-Ireland face and thick white hair combed back, as much a part of Pittsburgh as the waters of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers. The massive defensive tackle was an African American born in segregated Temple, Texas; dark and handsome, he played football with an anger that even he did not understand. Mean Joe knew the outline of the Chiefs story, that he mightve become a priest, but became a gambler instead, and that he played a semipro football game against Jim Thorpe, and mightve won an Olympic gold medal in boxing in 1920, and that he was pals with the old fighter Billy Conn and with Tip ONeill, Speaker of the US House of Representatives. He knew that when the old man took his night strolls through his neighborhood, the thugs didnt rob him, they protected him.

Mean Joe called him Mr. Rooney, as everyone did, never the Chief. That was an endearing nickname given by the youngest of his five sons, the twins, Pat and John, for his resemblance to the actor who played editor in chief Perry White on the television show Superman. Among all Steelers players dating to the teams founding in 1933, Mean Joe was the Chiefs favorite. The old man was a tough guy, too. At a 1975 practice, Terry Bradshaw completed a pass to rookie running back Mike Collier, who turned to the sideline and ran over the Chief. He knocked him flat, snapped his cigar in half. Collier froze as the trainer and the Chiefs driver rushed to his aid. But the Chief, at seventy-four, stood, brushed himself off, and eased Colliers fears: Thanks, Mike. I needed that.

Mean Joes appreciation for those Bances Aristocrat cigars grew with his appreciation for the Chief. Now, Mean Joe is a grandfather, his toddler granddaughter calls him Gumpa, his beard is flecked with gray, and he is nearly the same age as the Chief was in 1969 when they first met. Whereas once he threw his body around on the field like a desperado, now he moves slower, creakier. Mean Joes emotions never were far from the surface, and now he turns sentimental. He has filed away postcards the Chief wrote to him and his wife, Agnes, usually hellos from racetracks or Catholic shrines. He even kept one of those unsmoked cigars long after the Chiefs death as a memento of a defining friendship in his life. He remembers the Chiefs handshake, the way he put his small hand in his and held it there, a little longer than most men would.

Franco Harris returns to Pittsburgh International Airport late at night from another business trip. His frame is fuller, his hairline receding, yet he remains, unmistakably, Franco. As he approaches the lobby escalators, nearing the Immaculate Reception statue, hell see recognition spread across a bystanders face: the eyes wide, the mouth agape, and then... the request: Franco, would you, uhm, mind? The bystander wants to take a cell-phone photograph of Harris standing next to his famous likeness. Harris knows that if he poses for one, hell be asked to pose for five more. He consents, nearly always. This is his way. This is his town. Mean Joe calls him Mister Pittsburgh.

The statue of Harris is colorful and life-sized, the running back in black and gold bending forward on the run to make the shin-high catch that stunned the Oakland Raiders in a 1972 playoff game at Three Rivers Stadium, named by NFL Films the most controversial play in league history. Along the edge of Pittsburghs north shore, there are statues of televisions Mister Rogers and Bill Mazeroski, and by PNC Park, of Roberto Clemente, Pops Stargell, Honus Wagner, and several Negro Leaguers, including Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige. In this city that reveres them, only two of the 1970s Steelers are so honored, Harris, and the Chief, seated in bronze at Heinz Field.

Phil Villapiano was the Raiders linebacker covering Harris on the play that, to him, remains a great American tragedy. Im gonna tackle that fuckin airport statue one of these days, Villapiano tells me, half in jest. Franco can tell the police, I know who did it!

Baseball has the New York Yankees of the 1920s, basketball the Boston Celtics of the 1960s, and football the 1970s Steelers.

The rise of sports empires is a matter of talent and timing. Baseball in the 20s had moved beyond the Black Sox scandal into the live-ball era, and basketball in the 60s flourished with an end to the whites-only game. In the 70s, as television became an American phenomenon, football became its most popular show, and the Super Bowl virtually a national holiday. And no team celebrated more often than these Steelers. It was, tight end Randy Grossman would say of being a Steeler during that time, almost like living in a wonderland.

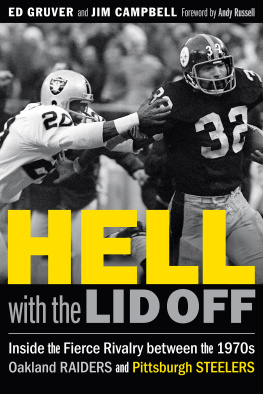

The Steelers rose like the sun over a landscape that once belonged to Lombardis Packers, the defining dynasty of the leagues first half century, and the team that fired the American imagination during the 1960s, when football first moved past baseball as the nations preferred pastime. Pittsburgh won four Super Bowls in six seasons between 1974 and 1979, its feat unmatched in the postmerger modern era. Its record during that span was 80-22-1. The Steelers won Super Bowls against Minnesota, Dallas (twice), and the Los Angeles Rams, and their intraconference blood rivalry with Oakland brought suffering to both sides. The 1970s Steelers sent a dozen men to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio: nine players, head coach Chuck Noll, Art Rooney Sr., and his son, Dan, who emerged as the Steelers day-to-day chief executive and later became within the NFL much like John Quincy Adams to his fathers John Adams, a founding familys second generation risen to power. The Steelers likenesses are cast in bronze: Mel Blounts shaved head reflecting in a spotlight, Mike Websters neck thick and muscular, and the bearded Jack Ham, half smiling, as if he knows the next play is coming at him.

The story line in 1974 was too good to be missed by the sports press. Everyone wanted the Chief, footballs lovable loser for forty years, to win his first NFL championship, and that wish extended far beyond a derelict steel town. Art Rooney Sr. was an American archetype, up from the streets, a Daily Racing Form in one hand, his leather-bound prayer book in the other. By habit, he dashed off thousands of postcardseach only a couple sentences, always handwrittento family, friends, and acquaintances, including one to me after I interviewed him in 1985 for a story about sports in Pittsburgh. His language was quaint and dated, still stuck in the 1920s. He used terms like yeggs, greasy bums, and Hey Rube (a free-for-all fight), expressions that passed from the language when carnivals stopped coming to town. It wasnt that the Chief needed to win a Super Bowl. His life, and his achievements, already had been certified. He had been a big winner with the Thoroughbreds. But the NFL publicity machine dreamed that the old man might one day hoist a Lombardi Trophy, for he was as likable as anyone the league had known; his Steelers players felt the same way, and figured he might have one last chance.