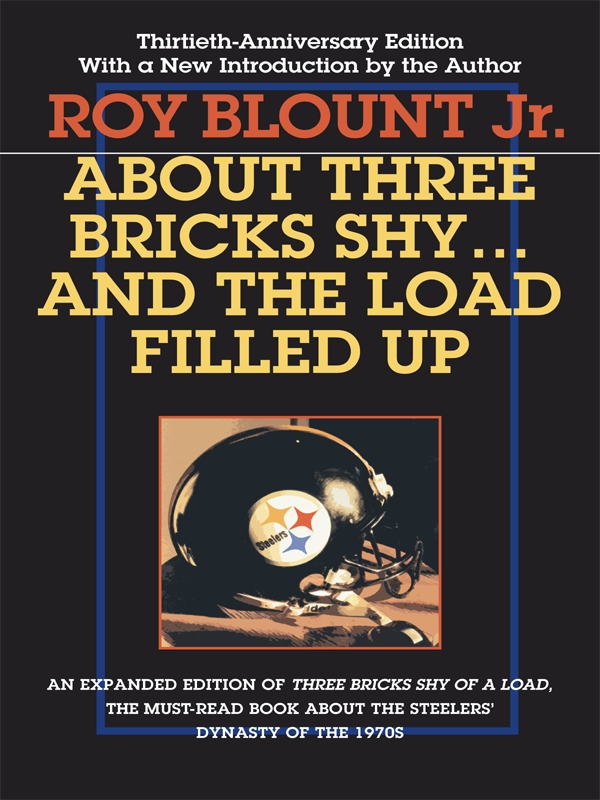

Roy Blount Jr. is the author of seventeen books, including Be Sweet, Roy Blount's Book of Southern Humor, If Only You Knew How Much I Smell You, and, most recently, Robert E. Lee, a brief biography. He is a contributing editor of the Atlantic and a columnist for the Oxford American, and he appears regularly on NPR's Wait, WaitDon't Tell Me. He was a staff writer at Sports Illustrated when he wrote his first book, About Three Bricks Shy of a Load, which he expanded into About Three Bricks ShyAnd the Load Filled Up after covering the Steelers of the seventies for several publications, including Esquire, Inside Sports, and the New York Times.

Published in 2004 by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa. 15260

Copyright 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1989, 2004 by Roy Blount Jr.

All rights reserved.

About Three Bricks Shy of a Load was originally published in hardcover in 1974 by Little, Brown and Company and in paperback in 1980 by Ballantine Books.

Portions were first published in Sports Illustrated.

ISBN 0-8229-5834-1

eISBN 978-0-8229-7968-5

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

TO ANDRE LAGUERRE, WHO CONCEIVED THIS PROJECT,

ART ROONEY, WHO CONCEIVED THE STEELERS,

AND MR. AND MRS. R. A. BLOUNT

WHO CONCEIVED

THE AUTHOR

MAY ALL OF THEM PARDON SOME OF THE LANGUAGE

INTRODUCTION

Franco Harris, who hated getting hit, told me something once, about running with the ball, that I didn't get down in my notes. It was something to this effect: as much as he wanted to comprehend the whole problem of a long run, to anticipate the whole open-field maze and to improvise a continuous mind-body flow of cuts and angles that could only end in the end zone.

Essentially what he said was, you can see too many possible tacklers. Not so much because you're anxious, hearing footsteps in that sense, as because you're trying for too ingenious a solutionwanting to fake out more tacklers than necessary. Coach Chuck Noll's catchphrase, paralysis of analysis, cuts to the quick of the mattertoo quickly for my satisfaction, but then I'm wary of coaching (and I didn't give Noll enough credit in this book). As I get older I register more tacklers, and feel tired. But I wrote this book when I was young, for a writer, and my mind was bursting with Steelers.

In the seventies giants walked the earth, and they didn't waddle, either. Guards didn't weigh three to four hundred pounds. When Moon Mullins was pulling out ahead of Franco on a sweep, he weighed about the same, 230 or so, as Franco. He was a positive addition to the run's complexity. A 400-pound blocker can't pull. Mean Joe Greene, with his insistent sense of fitness (he picked the ball up from the line of scrimmage once and flung it into the stands), would have harpooned and rendered a 400-pound blocker before the fat stopped jiggling.

Not only are today's linemen too big, they aren't funny enough. I see Warren Sapp of Tampa Bay holding forth in interviews, and to me he's a cover act, trying to do Dwight White without the sparkle.

So I sound like an old fart. So sue me. When I was a thirty-something fart, the Steelers were in their golden age, winning four Super Bowls in six years, and I was hanging with them. Actually loafing with was the Pittsburgh term, then. I don't know whether it still is or not.

I do know that since this book was published in 1989as an expanded, updated version of my 1974 book about the 73 Steelershistory has proceeded.Twelve of the people involved in the great Steeler teams of the seventies are now officially immortalized: Art Rooney, Joe Greene, Jack Ham, Mel Blount, Terry Bradshaw, Franco Harris, Jack Lambert, Chuck Noll, Mike Webster, Dan Rooney, Lynn Swann and John Stallworth are in the National Football League's Hall of Fame. And there's no reason in the world that L. C. Lover Cool Greenwood isn't among them, and how about Dwight White? Donny Shell? Andy Russell? How about me?

Okay, I didn't play. But I did do a lot of heavy-duty listening, and I did write the original core of this book in three months, on a manual typewriter, sleeping from nine to five and writing all night, busting a gut to see the whole field presented by the material, and feeling the book constantly getting away from me, because the stuff I had to work with was so good. When I hit a wall, I would remember what Ray Mansfield and Bruce Van Dyke told me you had to do when you were hurt: play through it. (A perhaps less salutary corollary to that was, when you feel like you're getting drunk, drink through it.) Iron men and wooden ships! Mansfield used to exclaim, by way of evoking old-school values. I wish I were back there wrestling with that raw material instead of sitting here adding another layer of varnish. (In the second chapter, by the way, there's a typo where Mansfield says to Van Dyke, I drove it. That's supposed to be I'd've done it.)

Since my day the Steelers have been to the Super Bowl once. Andget thisthey lost it. In the seventies, the Steelers had the biggest payroll in the NFL, but their highest paid player was Terry Bradshaw, who never got more than $400,000. Lambert got $200,000. The offensive linemen made considerably less than $100,000. Even adjusted for inflation, those figures are maybe a third of what players that good today can get, because they can become free agents represented by hotshot agents who negotiate multimillion-dollar contracts. In 1998 Ed Bouchette of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette asked a leading player agent to estimate how much the old Steelers would be worth on the 98 market. To sign just twenty-two starters from the seventies, the agent figured, would cost $91.8 million. In 98 each NFL team had a salary cap, for all fifty-three players on the roster plus injured ones, of $51.5 million.

Bouchette quoted Jim Boston, who was the Steelers chief negotiator in the seventies, as saying the dynasty Steelers could never have been kept together in the nineties: They would have gotten a cup of coffee as they passed through. Market freedom has prevented the Steelers from holding on to Rod Woodson, Levon Kirkland and other horses who might have started a new dynasty.

Any such dynasty, however, would get its butt kicked by the dynasty of my day. Only now can we realize how irreproducible this book is. You had to have great characters who were athletes rather than mounds of flesh and were funny without being derivative, and you also had to have the rightwhich is to say, exploitativeeconomic conditions. Toward the end of this book's chronicle of the 73 season, you may notice, there is a reference to L. C. Greenwood's having signed with the rival World Football League. As it happened, that league foldedbefore his Steeler contract ran out. Otherwise L. C. would have been somewhere else, making money commensurate with his uniqueness. Can you imagine the dynasty without L. C.? Wearing that gold chain with the bangle formed by the letters TFTEISYF, which, he explained when I asked, stood for The first time ever I saw your face? Right there in that corner of the locker room, L. C. of Mississippi next to Craig Hanneman of Oregon, numbers 68 and 67, respectively, you had the cast for a great buddy movie. And panning around to the right, we see, for instance, number 63, Ernie Holmes. Where else would I have gotten to know a man who shaved his head in the shape of an arrow?

So it was a rare moment in history that I had the great fortune to be a tangential part of. Heady timessee particularly the chapter herein regarding Super Bowl 75. Even some of the players have said they didn't realize how good it was until it was over.