For Murray Goldman

For Murray Goldman

Contents

Introduction

Stefan Nadelman In 1956 my grandfather Murray Goldman acquired the lease for the Terminal Bar near New Yorks Times Square. This was a dramatic career shift for him. For years he had run a dry-cleaning business in Queens. Back then the machines were so big they could only be housed in factories, so Murray would pick up the garments from businesses, bring them to a factory where hed pay to have them cleaned, and then make his return deliveries. He was basically a dry-cleaning middleman. At the time, his brother-in-law Bernie and cousin Arnie ran a Manhattan bar called the Peppermint Lounge, and they encouraged him to get in the business, too.

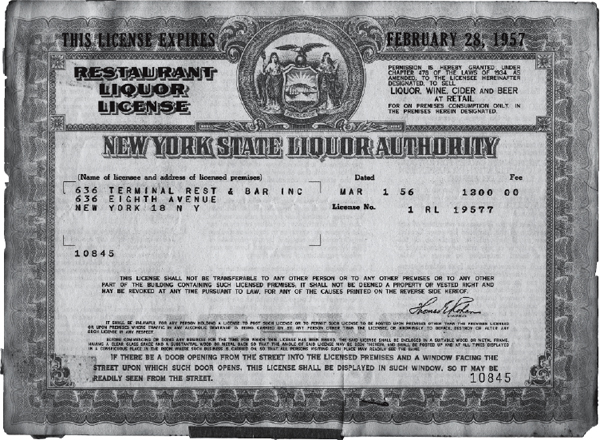

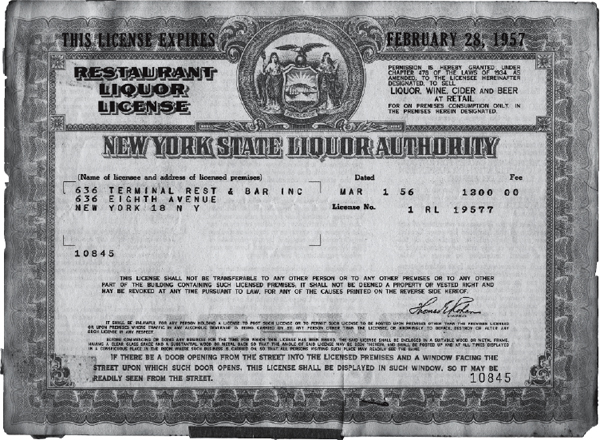

So he sold the dry-cleaning route and, with Bernies help, became the proprietor of the Terminal Bar.  The Terminals liquor license from 1956

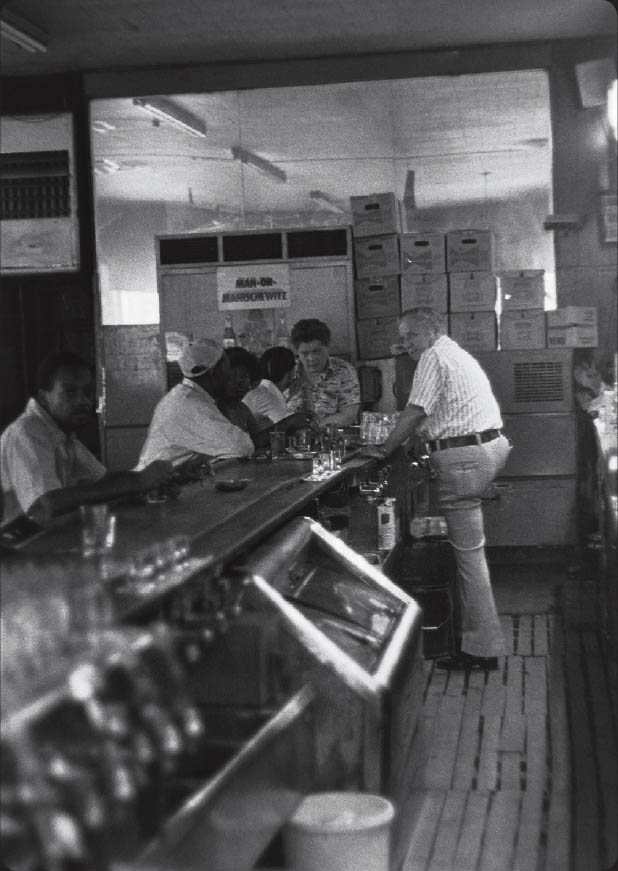

The Terminals liquor license from 1956  Murray Goldman (left) at the Terminal Bar in the late 1950s

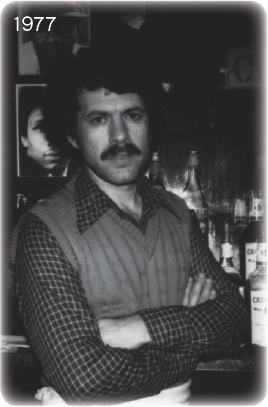

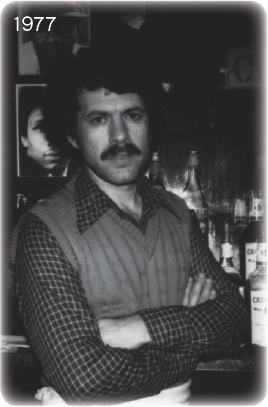

Murray Goldman (left) at the Terminal Bar in the late 1950s  Shelly behind the Terminal Bar

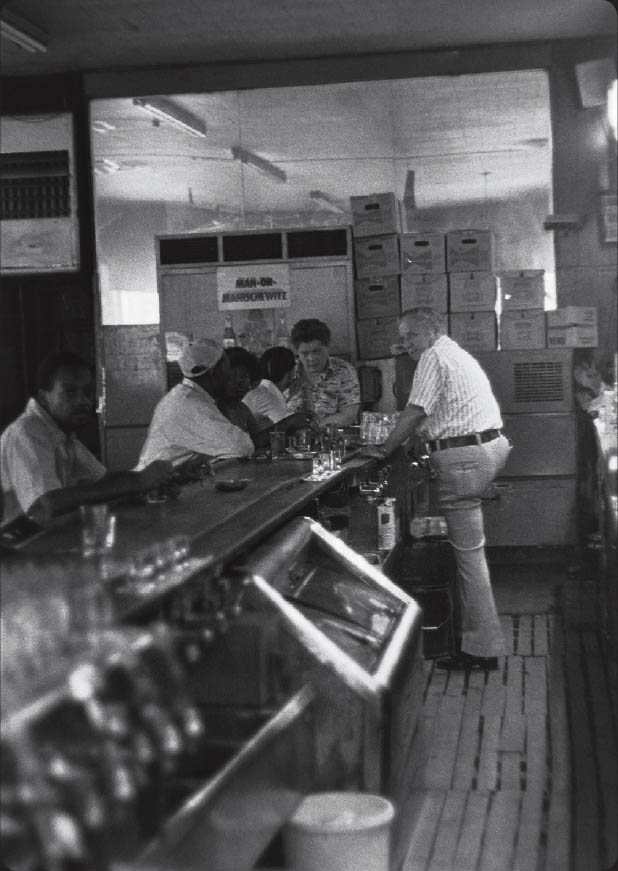

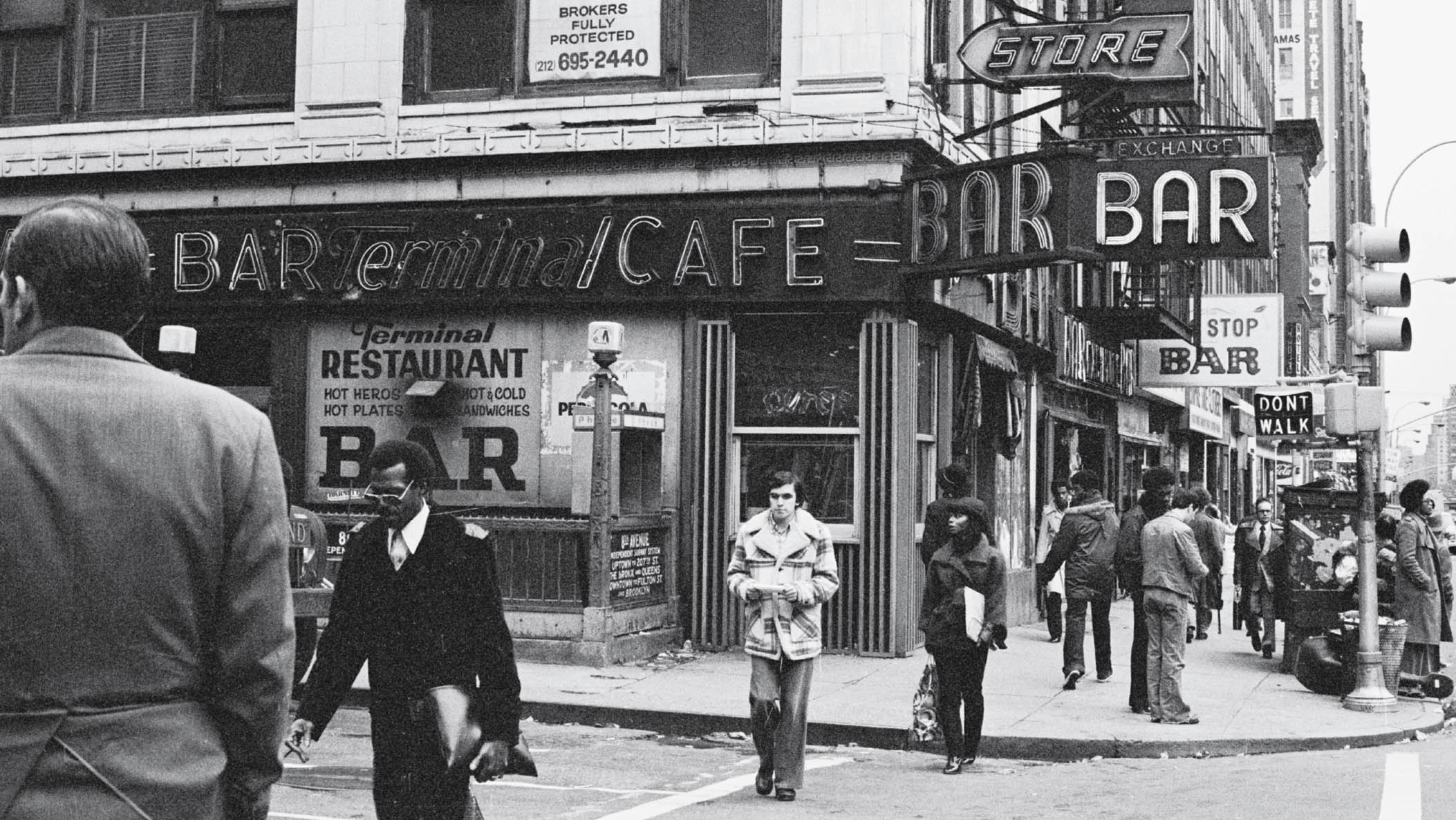

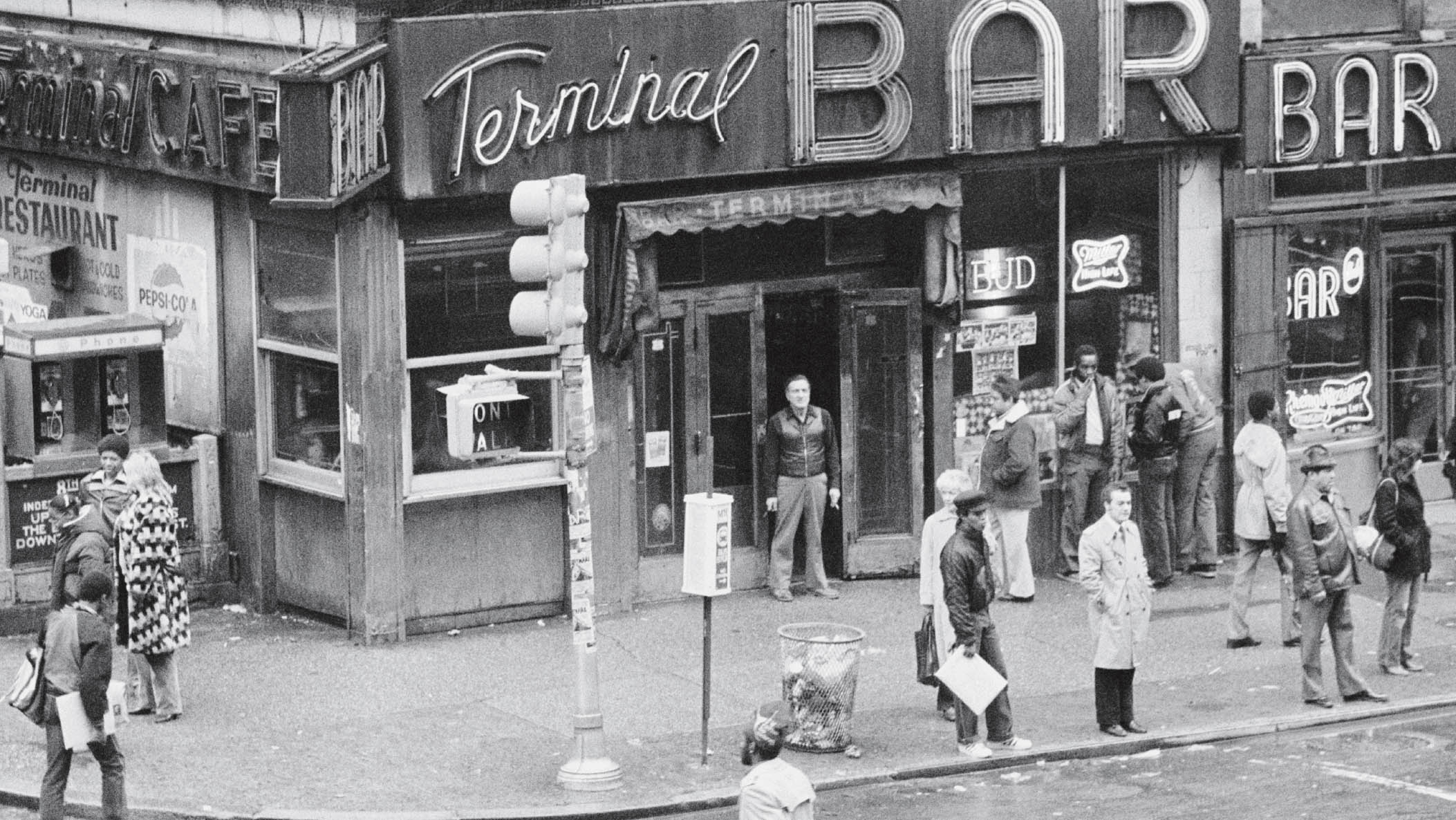

Shelly behind the Terminal Bar  The bar shot from the Port Authority In the beginning it was a challenge to make the bar work. Murray was always short on money to keep it afloat. He was in constant fear of being shut down by the Department of Health or the Liquor Authority. But what he lacked in experience and business acumen, he made up for with his personality. He eventually got his finances under control, but he never had a surplus of funds.

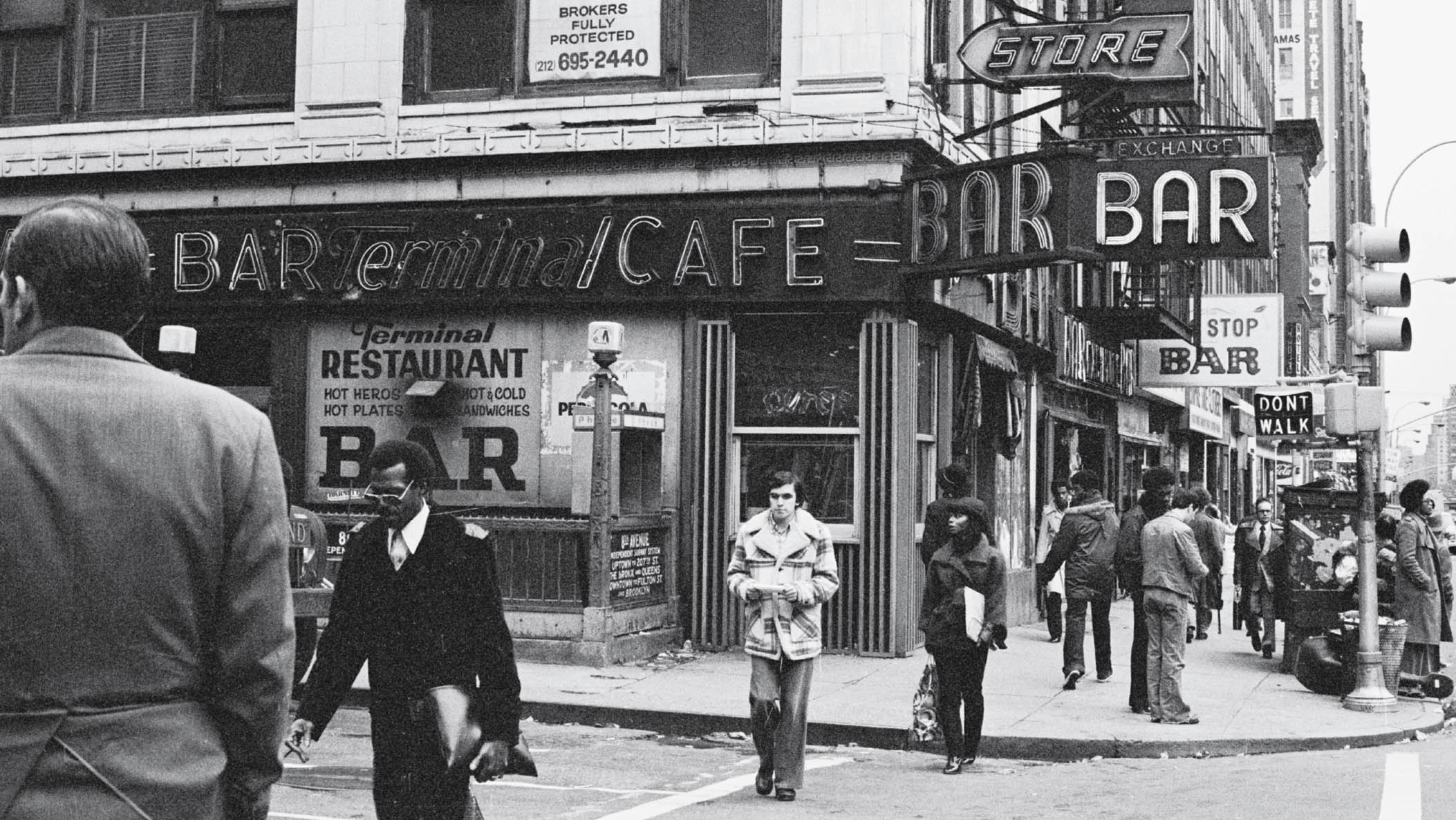

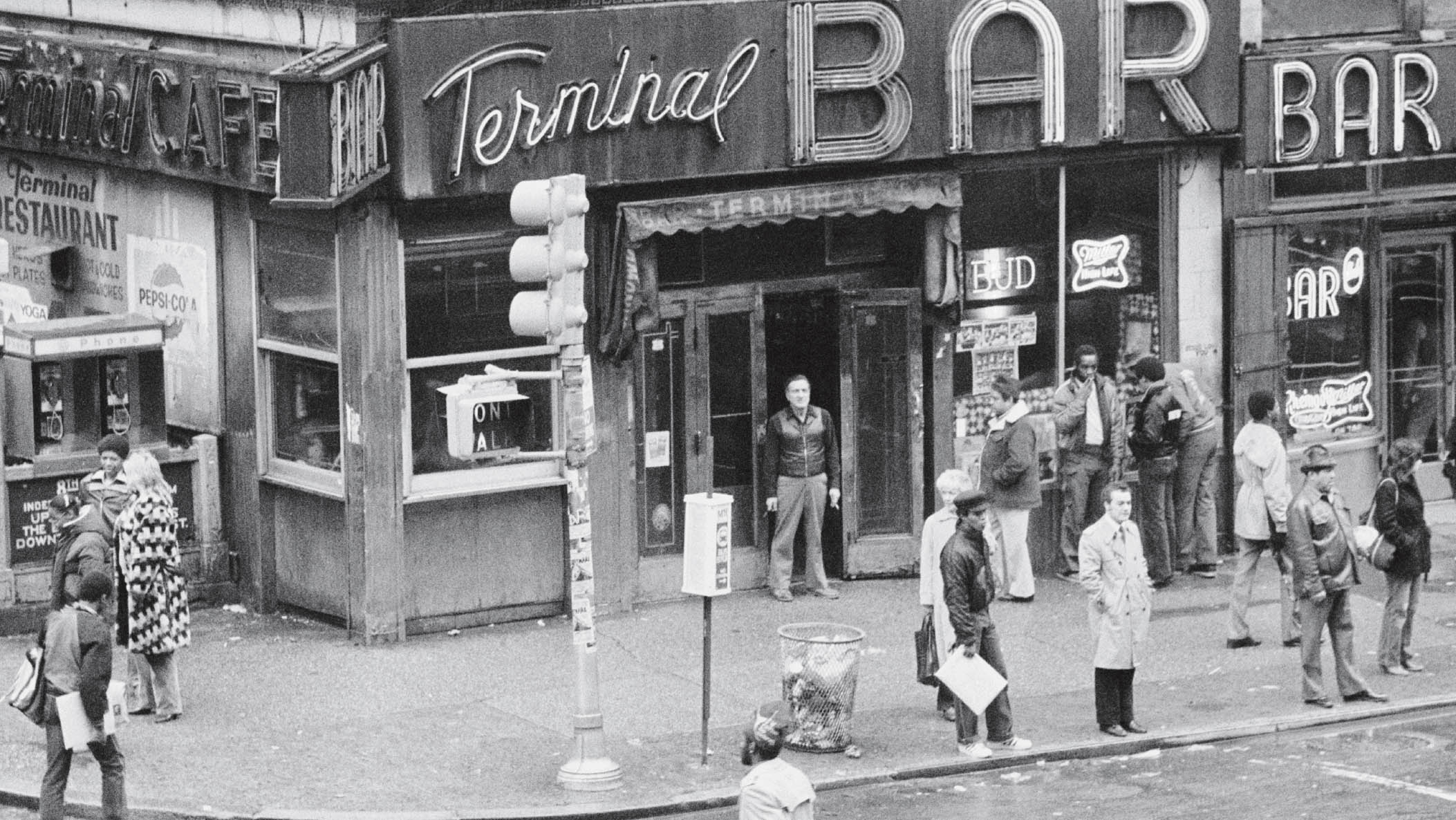

The bar shot from the Port Authority In the beginning it was a challenge to make the bar work. Murray was always short on money to keep it afloat. He was in constant fear of being shut down by the Department of Health or the Liquor Authority. But what he lacked in experience and business acumen, he made up for with his personality. He eventually got his finances under control, but he never had a surplus of funds.

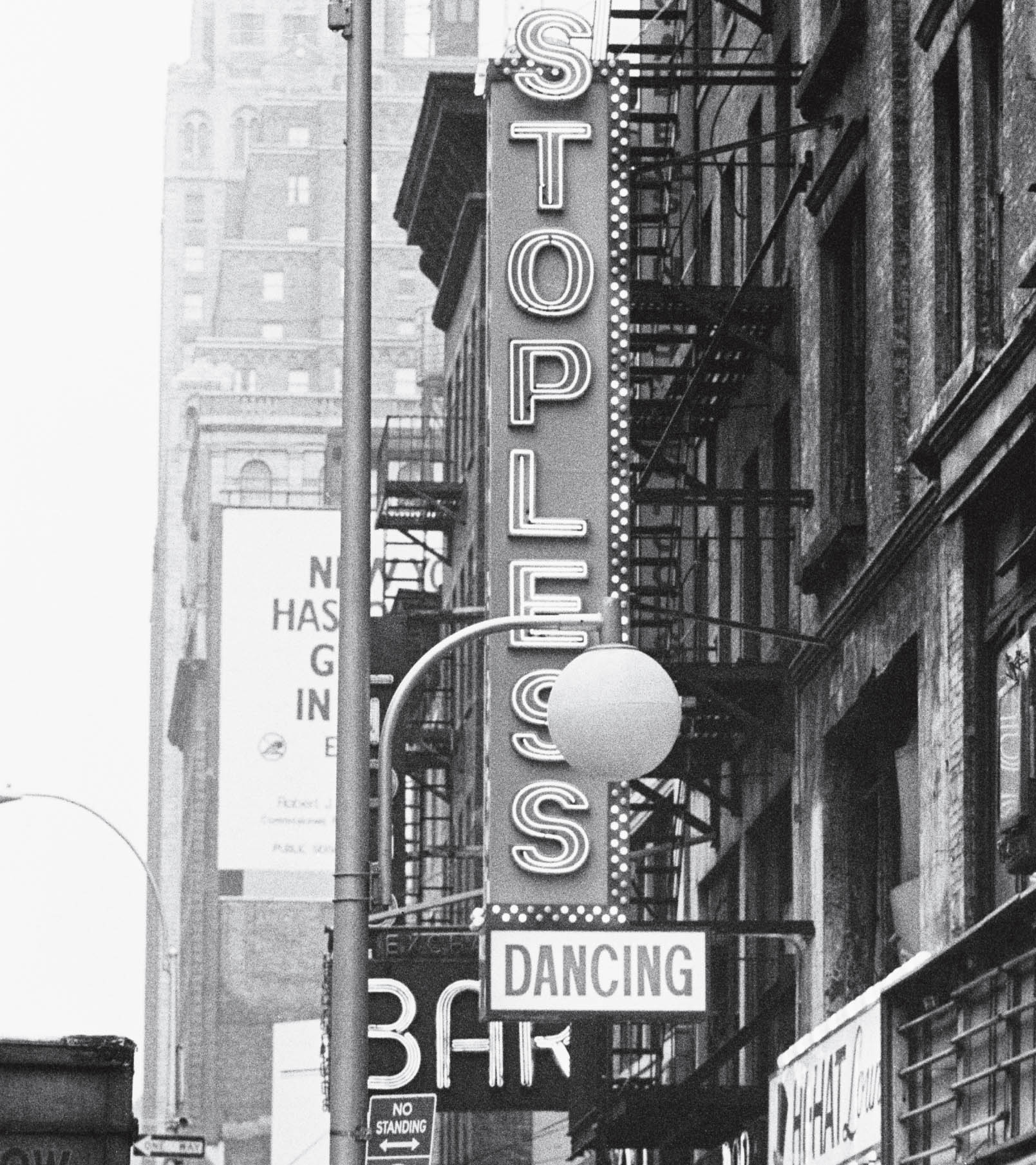

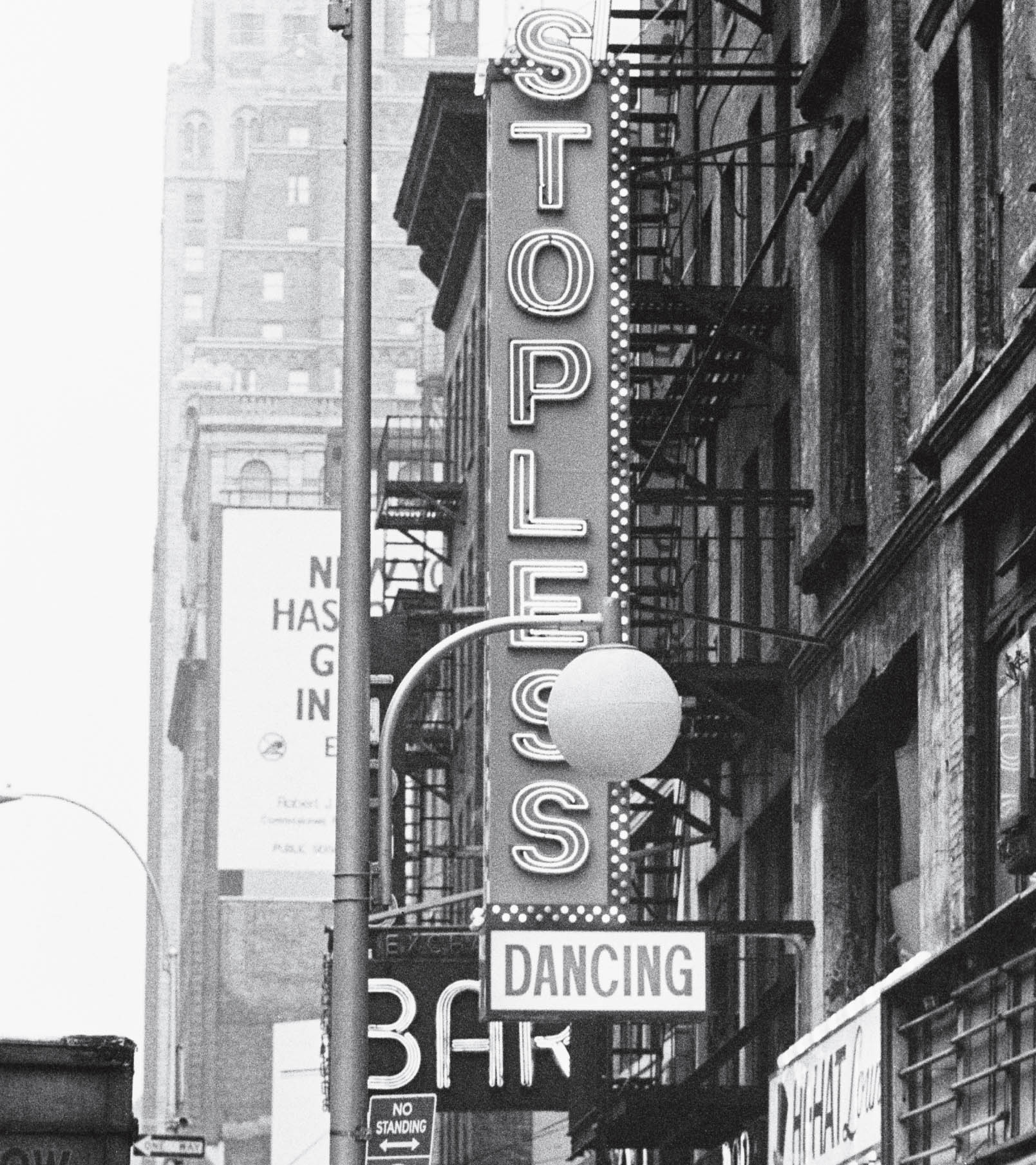

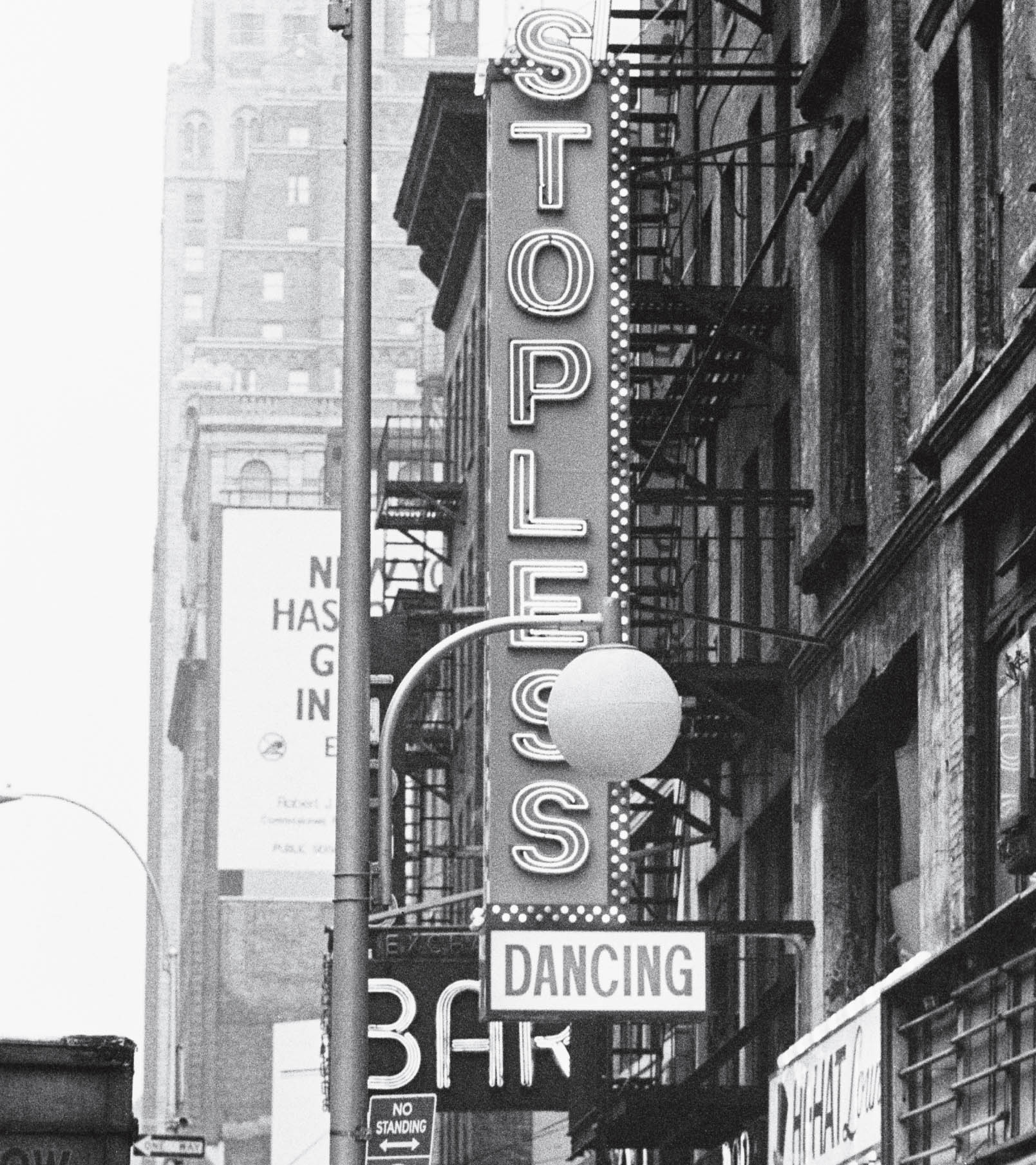

He and my grandmother lived in a modest apartment in Rego Park, Queens; owned an Oldsmobile; and went on plenty of complimentary cruises to the Caribbean funded by liquor companies promoting their products to bar owners. Over the years he became an important figure in the Times Square scene. People called him The Godfather. The atmosphere, demographic, and name of the Terminal Bar were dictated by its location: directly across the street from the Port Authority Bus Terminal, on the southeast corner of Eighth Avenue and West Forty-First Street. This particular intersection was, and still is, a thriving hub where all strata of society converge. It provided an endless stream of one-off customers wandering in for a drink.

During the day, these were the folks who worked in the area, on their way to their jobs or on their way home, while at night, the bar was populated by the regulars who mostly lived in the area. It was a mix of transient and neighborhood culture. My grandfather not only loved the idea of owning a bar, he loved his customers. With his compassionate demeanor, he assumed a patriarchal role and earned the trust of all who patronized the Terminal. In doing so, he maintained an atmosphere of peace in the establishment, despite its reputation for being the roughest bar in towna myth propagated by the press. The Terminal Bar was a community, not unlike every other semisuccessful bar.

The only difference was that Murrays son-in-lawmy father, Sheldon Nadelmanbegan working there in 1972, with a camera to record the customers faces and a memory to recall their stories. Growing up, I knew the Terminal Bar as the mythical place where my grandfather and father worked. Neither of them shared much detail about it, because a kid should generally be sheltered from bar culture. But when I was eight years old my dad brought me to the Terminal, and I remember being given a Boba Fett Star Wars figure by one of the customers. My father gave me permission to accept the gift, which I did with fervor. My father also received gifts, as well as steals, from his customers over the years.

He was a guy whod take something off your hands for free, or for a price if it was worth it. Clothes, books, artwork, furniture, camerasmy father says he could have bought a watch every day. Practically every room in my house growing up contained an item procured from the bar. My grandfathers Queens apartment was also fitted out with gifts given to him at the bar. My childhood house might as well have been a gallery. Empty wall space was a foreign concept to my father, so he filled our small split-level colonial with art.

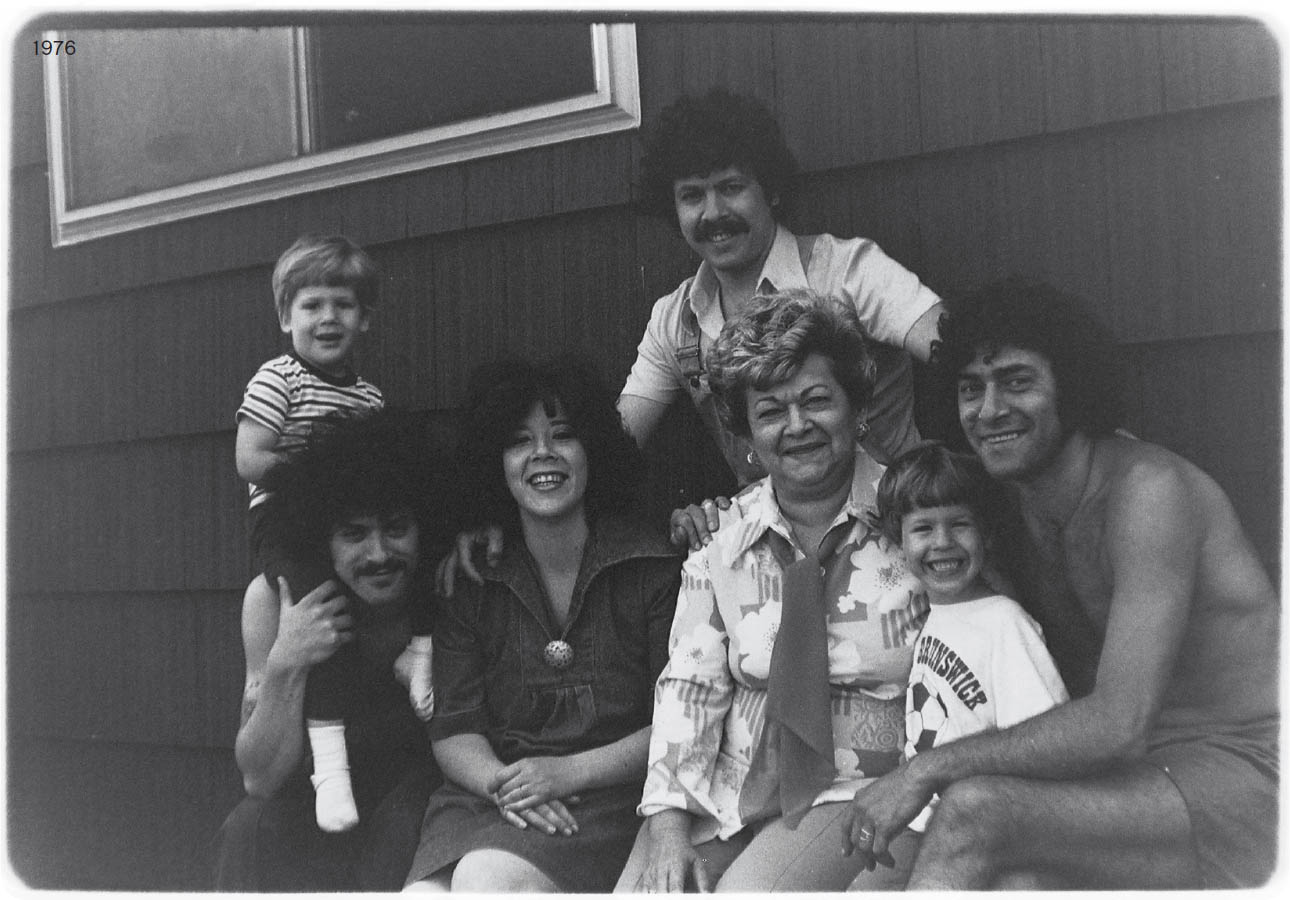

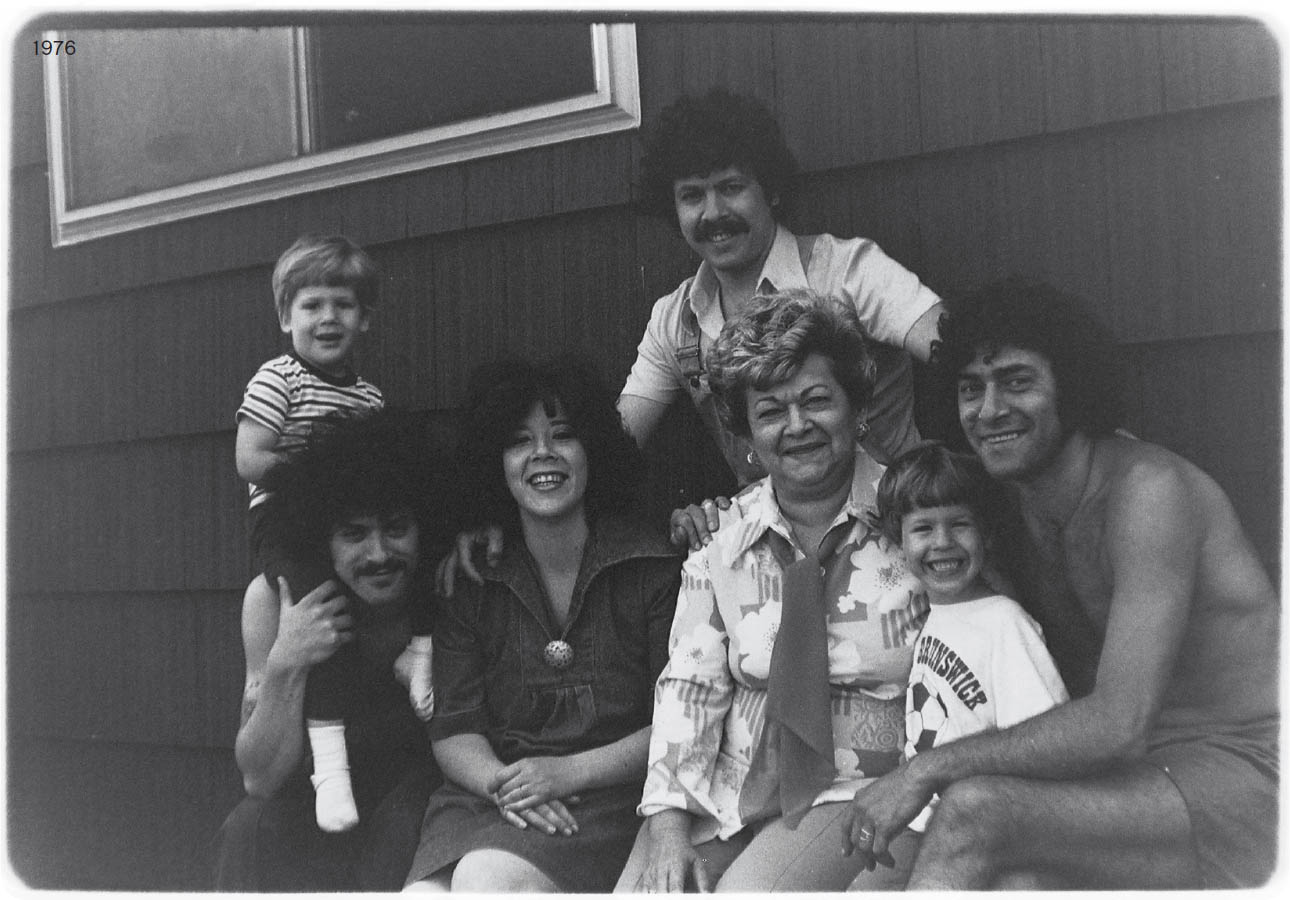

In the beginning his own paintings on irregular pieces of wood hung on the walls, but as soon as his brushes and paint were set aside for his Pentax, photography became his medium of choice. Interspersed with his artwork and M. C. Escher prints were black-and-white portraits of faces belonging to strangers. I never gave those photographs much thought; they were just background, part of the landscape in which I grew up.  The Nadelmans (left to right): me, Chuck, Rita, Shelly, Minna, Cary, and Michael

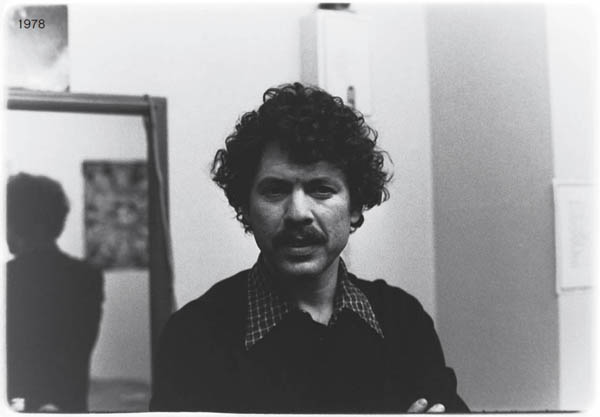

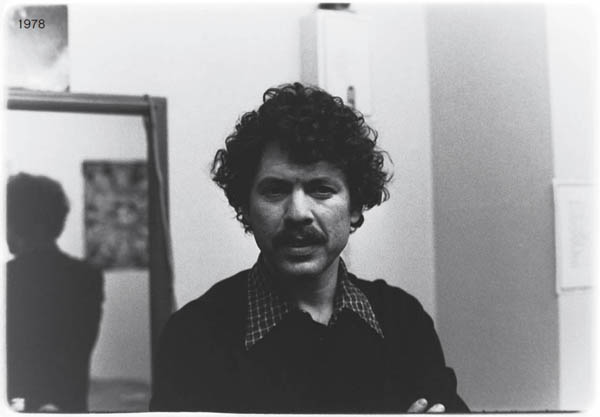

The Nadelmans (left to right): me, Chuck, Rita, Shelly, Minna, Cary, and Michael  Of the 2,600 photos my father took from 1973 to 1981, only 22 were self-portraits.

Of the 2,600 photos my father took from 1973 to 1981, only 22 were self-portraits.

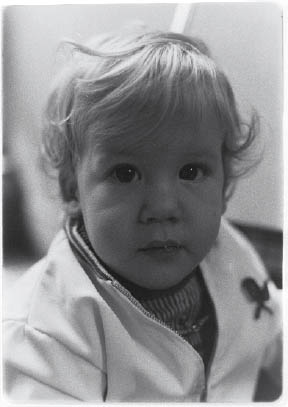

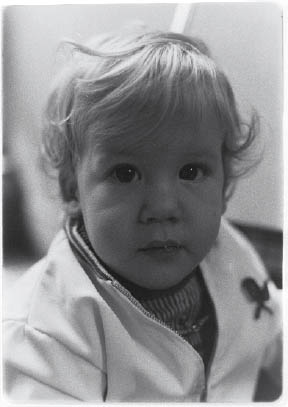

That shows quite some restraint, given that nowadays many people take selfies on a daily basis.  Me, in 1973 It was only after returning home from college that I saw this visual environment with fresh eyes and became interested in the vast, untapped collection of faces my father had photographed during his ten-year stint as a bartender at the Terminal Bar. The portraits he hung on the walls of our home were just the tip of the iceberg. I knew that thousands more were filed away in his binders of negatives, waiting to see the light again. I also knew that my father, disinterested in self-promotion, would never exhume this impressive archive voluntarily. In 2000 I took it upon myself to digitize all of his black-and-white photographs, with the goal of producing a short film about the Terminal Bar.

Me, in 1973 It was only after returning home from college that I saw this visual environment with fresh eyes and became interested in the vast, untapped collection of faces my father had photographed during his ten-year stint as a bartender at the Terminal Bar. The portraits he hung on the walls of our home were just the tip of the iceberg. I knew that thousands more were filed away in his binders of negatives, waiting to see the light again. I also knew that my father, disinterested in self-promotion, would never exhume this impressive archive voluntarily. In 2000 I took it upon myself to digitize all of his black-and-white photographs, with the goal of producing a short film about the Terminal Bar.

My intentions were twofold: I would premier my fathers work with the hope of rescuing him and his craft from obscurity while demonstrating my own skills as a filmmaker. I printed out a hefty stack containing thumbnails of more than 1,500 portraits and brought them to my father. I sat him down in the family room, fitted him with a microphone, hit record on a tripod-mounted camera, and dropped the printouts of his Terminal Bar pictures in front of him. I eventually extracted from these interviews the photo captions in this bookhis recollections of what went on inside and outside the bar, as well as his memories of the patrons names and personalities. It took two days to go through all the material. This was the first time he was seeing any but a small fraction of the photographs since he had developed the negatives twenty to thirty years earlier, and I could see his eyes light up as the memories came flooding back.

Next page

For Murray Goldman

For Murray Goldman

The Terminals liquor license from 1956

The Terminals liquor license from 1956  Murray Goldman (left) at the Terminal Bar in the late 1950s

Murray Goldman (left) at the Terminal Bar in the late 1950s  Shelly behind the Terminal Bar

Shelly behind the Terminal Bar  The bar shot from the Port Authority In the beginning it was a challenge to make the bar work. Murray was always short on money to keep it afloat. He was in constant fear of being shut down by the Department of Health or the Liquor Authority. But what he lacked in experience and business acumen, he made up for with his personality. He eventually got his finances under control, but he never had a surplus of funds.

The bar shot from the Port Authority In the beginning it was a challenge to make the bar work. Murray was always short on money to keep it afloat. He was in constant fear of being shut down by the Department of Health or the Liquor Authority. But what he lacked in experience and business acumen, he made up for with his personality. He eventually got his finances under control, but he never had a surplus of funds. The Nadelmans (left to right): me, Chuck, Rita, Shelly, Minna, Cary, and Michael

The Nadelmans (left to right): me, Chuck, Rita, Shelly, Minna, Cary, and Michael  Of the 2,600 photos my father took from 1973 to 1981, only 22 were self-portraits.

Of the 2,600 photos my father took from 1973 to 1981, only 22 were self-portraits. Me, in 1973 It was only after returning home from college that I saw this visual environment with fresh eyes and became interested in the vast, untapped collection of faces my father had photographed during his ten-year stint as a bartender at the Terminal Bar. The portraits he hung on the walls of our home were just the tip of the iceberg. I knew that thousands more were filed away in his binders of negatives, waiting to see the light again. I also knew that my father, disinterested in self-promotion, would never exhume this impressive archive voluntarily. In 2000 I took it upon myself to digitize all of his black-and-white photographs, with the goal of producing a short film about the Terminal Bar.

Me, in 1973 It was only after returning home from college that I saw this visual environment with fresh eyes and became interested in the vast, untapped collection of faces my father had photographed during his ten-year stint as a bartender at the Terminal Bar. The portraits he hung on the walls of our home were just the tip of the iceberg. I knew that thousands more were filed away in his binders of negatives, waiting to see the light again. I also knew that my father, disinterested in self-promotion, would never exhume this impressive archive voluntarily. In 2000 I took it upon myself to digitize all of his black-and-white photographs, with the goal of producing a short film about the Terminal Bar.