In the manner of sport at its best, this book was in the truest sense the result of a wholehearted team effort.

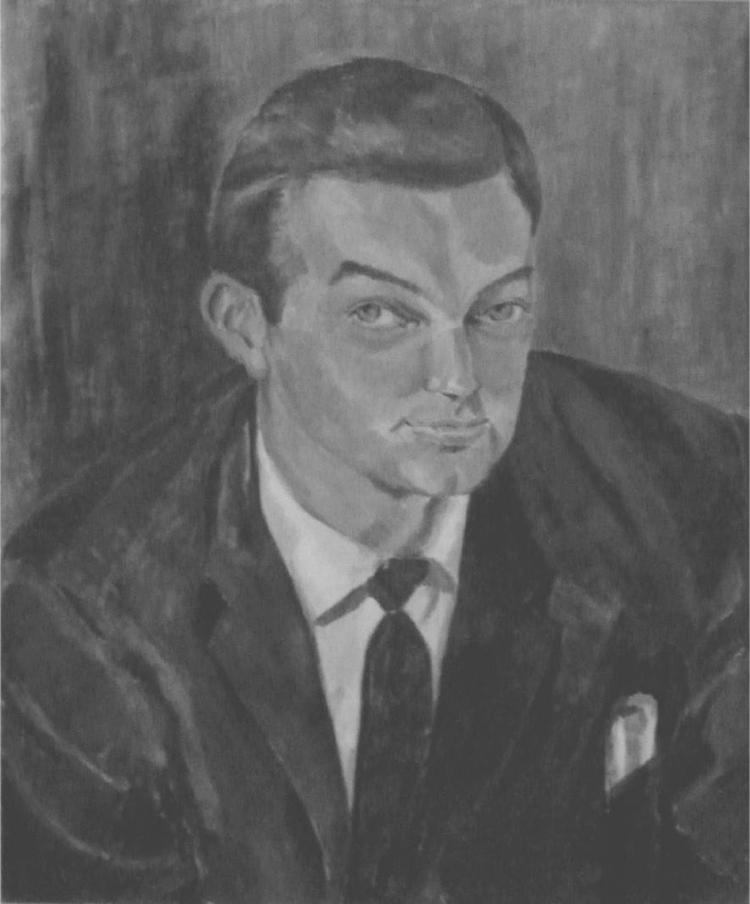

Very special thanks are with the Benaud family. Richies wife Daphne and his brother John were wonderfully supportive and towers of strength throughout, playing the necessary sheet anchor role as the book evolved. We are grateful for the support of Richies sons, Greg and Jeff, whose personal reflections provide a wonderful postscript.

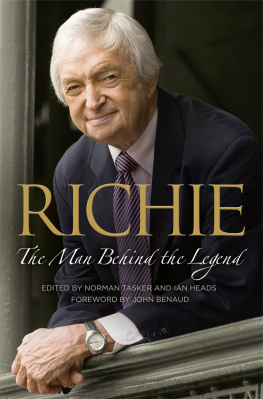

Our thanks also go to the people at Channel Nine, not least for granting us permission to use excerpts from the tribute to Richie that was broadcast so soon after his death, and for helping us locate Brendan Read, whose cover photograph is superb. We appreciate the continued support of Pan Macmillan Australia and the Opus Group, and the efforts of those involved in the physical making of the book: Graeme Jones, Luke Causby, Robert Stapelfeldt, Elizabeth Cowell, Sarah Shrubb and Steve Keipert.

And, crucially, we must thank the wonderful cross-section of cricket people and the many contributors from outside the game who so generously shared their time and personal memories and reflections of the late Richie Benaud. The co-operation of friends, teammates, opponents, old school mates, workmates and others who had encountered Richie along the way was wonderfully selfless, precise and professional. We suspect that Richie, meticulous in both work and play throughout his life, would have approved, though being the private man he was ever modest about his own considerable achievements and never a seeker of attention the suspicion is he would have flinched at the sheer volume of words and photos that flowed onto the desk of publisher Geoff Armstrong.

Our hope is that, in the quality of the contributions and the breadth of its coverage, this book does justice to a great and popular Australian.

A CERTAIN MYSTIQUE

As long as cricket is played and wherever it is played, the public will always remember Richie Benaud.

Norm ONeill, 1964

BILL LAWRY

Bill Lawry made his Test debut during the 1961 Ashes tour and was a stalwart for the next decade, captaining Australia in 25 of his 67 Tests. He scored 5234 Test runs at an average of 47.15, and was the durable rock on which many a Test innings was built. When World Series Cricket started, Bill joined Richie Benaud in the commentary box and quickly became a fixture in the Channel Nine team. He remembers a much-loved friend and colleague who earned the respect of all who knew him

WHEN RICHIE LEFT US , I looked back on 78 years of life and realised I had been looking up to Richie Benaud for about 63 of them. I was maybe 15 when, like all aspiring young cricketers, I first followed his deeds as the glamorous new face of first-class cricket. When I made the Australian side in 1961 at age 24, he was my captain. He had a commanding aura about him and I was just one of the young blokes down the back of the bus.

When I began my commentary career at the advent ofWorld Series Cricket, Richie was our leader. He had nearly 15 years experience as a television commentator with the BBC; he was the doyen and we were all novices. We all looked up to him as the cool presence that made everything work.

Even in latter days, nobody ever doubted where we all stood in the pecking order. If we left the ground together at the end of a days play, the fans would make way for Richie with obvious respect, and he would move through them, head high and eyes fixed ahead. Tony Greig or Ian Chappell or myself might cop some lip, but never Richie. His dignity brought the same response from fans in the 21st century as it had from the likes of us, who had played cricket with him half a century before.

Richie was cool and calculating as a cricket captain. He maintained a certain mystique about himself. He didnt talk all that much; certainly he never ranted or raved as some captains might. As a result, his words carried so much more weight. What he said was gold and that attitude carried into his commentary career.

He was also highly principled. He stuck with what he thought was right, even in the most pressured of circumstances and up against the most powerful of people. When World Series Cricket came about, it was Richie who made it work, both in siding with it at the start and giving it his credibility, then as the face of a television coverage that was quite revolutionary. He gave us all confidence. When he appeared you somehow knew it was going to be a good day. He did have to work under enormous pressure, and the professional attitudes he exuded made it better for all of us.

It was, though, a whole new ball game and even Richie was asked to make some adjustments. At the BBC he had become used to the 90-second gap after each over when he could gather his thoughts and give a considered appraisal of what had taken place through the previous over. In the new commercial world of Channel Nine he couldnt do that just a quick score then off to an ad break. So more information had to be provided during an over.

I remember one occasion when we were on air together Richie was economical with his words and I was a new boy content to let him lead the way. A couple of overs were played out in relative silence, and then there was a phone call from Kerry Packer wanting to know what we were doing. He informed us in very clear terms that this was not the BBC, most of the people watching didnt have a clue about cricket, and we were supposed to be telling them what was going on.

Richie wasnt going to change or in any way dilute the commentary lessons he lived by: you only spoke if you could add something to the pictures. So the next over was again virtually word-free. After that, I thought keeping Kerry on side was a bit more important, so I started rattling on. The pattern sort of stuck.

In those early days, Richie did the presenting as well as commentating. He didnt have the small army of commentators we see today, or a Cricket Show or anything like that to help him fill the time at lunch or during other breaks in play. He would do 10 minutes before play started, to set the day up, then hed do another summary at lunch, before we crossed to the 18-footer sailing races as we did in those days. He did all the talking at tea and summaries at stumps. It was a lot of pressure, but he handled it with the same easy assurance that he had managed when he was the Australian cricket captain. Even when things went wrong, as they often did, he was in control. In tandem with a super producer in David Hill, Richie opened up a whole new era of sport on television. More cameras and at both ends of the ground jingles, coloured clothing, night cricket they all came in a rush as the public got on board and the modern game started to take shape.

I remain convinced today that WSC would not have worked without Richie. Lets face it, half of the cricket community was willing us to fail, and there was so much innovation it needed a really steady hand to put it all out there. Richie did that brilliantly, bringing the game into a new era decades earlier than may have been the case otherwise.

It had been like that on our 1961 tour of England, too. Richie was the first player to bring some theatrics to the game, jumping about in celebration and generally being more lively. His background as a journalist and the fact he did a BBC-TV course way before he ever got a job there meant that he knew how to work with the media. If there was a TV or film camera around he was a natural.