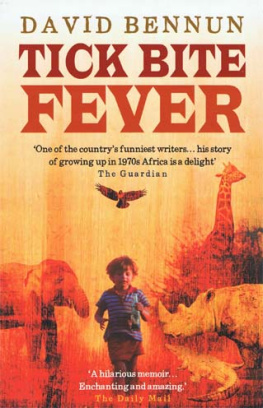

tick

bite

fever

DAVID BENNUN

EBURY

PRESS

Contents

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781409004646

www.randomhouse.co.uk

This edition published in 2004

First published in Great Britain, 2003

Text David Bennun 2003

7 9 10 8

David Bennun has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright owners.

First published by Ebury Press Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at www.randomhouse.co.uk

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780091897437

Typeset by Textype, Cambridge Cover design by Two Associates

Printed and bound by CPI Cox & Wyman, Reading, RG1 8EX

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

For my family

about the author

Award-winning.

Millionaire playboy David lives in Brighton, because its handy for my yacht. His interests include the arts, fine dining and breaking into nearby safari parks to fight lions with his bare hands. I fear my exploits may have been a little exaggerated, he says, with a modest chuckle. Good work. Heres your fifty quid.

Best Junior Dog Handler, Nairobi Kennel Club Show, 1981

acknowledgements

This ought to contain a long list of thank-yous. It doesnt.

Theres no shortage of people to whom I owe debts of gratitude. But I have to consider the embarrassing possibility that any such list might well outnumber the eventual readership of this book. So Ill keep it brief and hope that nobody takes offence.

Im deeply appreciative of my many friends and colleagues who over the years have supported me in my work; likewise, those editors who have paid me for it and even, now and then, printed it. Thanks to all of you, I have already got away with calling myself a writer for longer than I ever thought possible.

I must single out Ben Marshall and Jon Wilde, great writers and even better friends. If not for their help and encouragement, I might never have attempted a book. Blame them.

Im also very grateful to everyone who has assisted me with the book along the way. Needless to say, any errors, flaws and lapses of judgement are entirely their responsibility, while the good bits are mine alone.

Above all, my thanks and my love go to Kavita, without whom nothing would be worth doing in the first place.

prologue

Out of Africa,

with Some Relief

AFRICA-BOUND from Heathrow Airport, at 30,000 feet over the Mediterranean Sea, I politely announced that this had all been very nice, but Id like to get out now.

It was 1971. I was three, and already demonstrating the keen pragmatism of a child half my age. Over the next two decades, my understanding of reality failed to improve much.

My parents came to despair of me. What world do you live in? my father would ask, frustrated. It was a good question. We lived in Africa: first, briefly, in Zambia, after that in Kenya. Yet my Africa seemed to be set on an entirely different planet from theirs.

As I grew up, I would come to think of myself as being, by default, African. I didnt look, or sound, or act African, by any stretch of the term. Still, there didnt seem to be an alternative.

I should explain why we were flying to Africa that day in 1971. We were flying to Africa because it was a surefire means to get away from England, where my family had just concluded a spell of nine drab, grey, parochial years. Part way through that spell, I had been born in a place as far from exotic as it is from the equator: Swindon. It wasnt my idea.

To be fair to my parents, it wasnt their idea either. I came as a surprise, and they resolved to make the best of me. I dont doubt that they succeeded, given what they had to work with.

What they had to work with was me, the presumed subject of this book. But the book isnt really about me. It is about Africa, about my family, about the mishaps and calamities and freakish occurrences in which I was so often an unwitting pivot or accidental catalyst. It is about a life my own where I have figured largely as a baffled spectator. Others meet danger with cunning and fortitude; I overcame it through a mixture of blind luck and not falling over too often. My childhood passed in a haze of delirium familiar to me from several intriguing diseases, including the one that provides the books title. Maybe I never fully recovered from it. That would explain a great deal.

I moved back to Britain permanently over ten years ago. Since then, the level of weirdness in my life has dropped to approximately zero. I can tell myself it was all Africas fault, and none of mine. Occasionally, I even believe it. Thats why Ive stayed here in Britain. To keep the weirdness at bay.

When you already have enough weirdness to fill a book, there are only two things to do. The first is to sit tight and hope you dont encounter any more of it. The second is to fill a book.

chapter one

Family

Snapshots

WE ARE never the men our fathers were, my father, Max, once said to me. While I believe he was absolutely right, it would have been easy to take that comment the wrong way. But I know that he was thinking of himself and his own father, Naphtoli, rather than of me.

Naphtoli Toli for short was born in 1904, in Lithuania, into a family of tanners by the name of Misnuner. They ran a leather factory in the country town of Wilkomir, 50 miles to the north of the capital, Vilna. Wilkomir is still there, and so is the factory. The Misnuners are gone. They were massacred in the summer of 1941 along with every other Jew in the vicinity by the German Einsatzkommando 3 death squad and its enthusiastic local collaborators.

Toli eluded this catastrophe thanks only to the earlier misfortune of his father, Yitzchak. One day in 1926, Yitzchak had climbed into a giant tanning drum to clean it out. An employee, unaware, set the mechanism rolling. Yitzchak, as befitted a man who worked with rawhide, was a tough customer. He braced himself against the sides of the spinning cylinder for a full ten minutes before succumbing to dizzy exhaustion, and was tumbled into oblivion.

This left Toli in the charge of his uncles, of which he had several. They decided he should be sent to South Africa. Yet more uncles had set up another leather business in Port Elizabeth, on the Western Cape, where Toli was seconded in a junior capacity. He arrived that same year, a penniless young man with a letter of introduction, a chemistry degree and not a word of English.