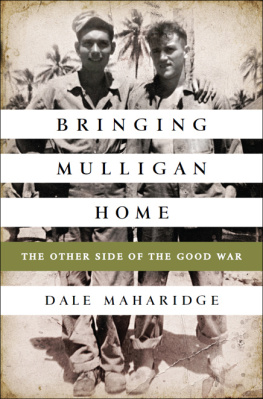

BRINGING MULLIGAN HOME

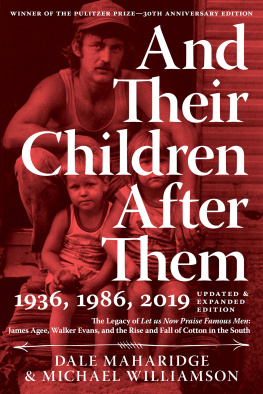

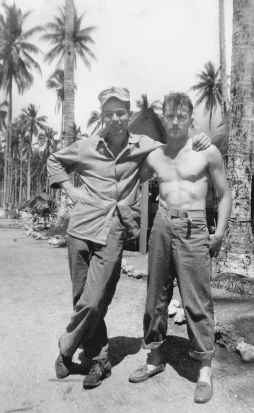

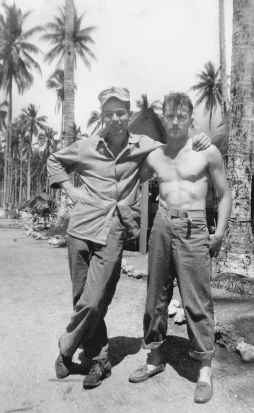

Herman Walter Mulligan and Steve Maharidge, Guadalcanal, 1944. Photographer unknown

BRINGING

MULLIGAN

HOME

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE GOOD WAR

DALE MAHARIDGE

PUBLICAFFAIRS

New York

Copyright 2013 by Dale Maharidge

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs,

a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Every effort has been made to secure permissions for all text and images reprinted in this volume.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book Design by Cynthia Young

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Maharidge, Dale.

Bringing Mulligan home : the other side of the good war / Dale Maharidge.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

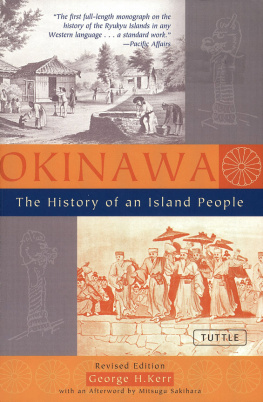

ISBN 978-1-61039-002-6 (e-book) 1. Maharidge, Steve, 1925 2000. 2. World War, 19391945CampaignsJapanOkinawa Island. 3. World War, 19391945VeteransUnited StatesBiography. 4. World War, 19391945Psychological aspects. 5. United States. Marine Corps. Marine Regiment, 22nd. Battalion, 3rd. 6. VeteransMental healthUnited States. 7. Fathers and sonsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

D767.95.O45M35 2013

940.54252294092dc23

[B]

2012039518

10987654321

In memory of Joan and Steve, my parents.

To the men of L Company, 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, Sixth Marine Division. Among some of those I came to know,

Arthur Bishop

Karl Brothers

Danny Cernoch

J. R. Collin

Bill Fenton

Fenton Grahnert

Frank Haigler

Edward Hoffman

Joe Lanciotti

Malcolm Lear

Jim Laughridge

Charles Lepant

Hank Markovich

George Niland

Frank Palmasani

George Popovich

Tom Price

Joe Rosplock

And to the civilians on Okinawa who wanted no part of war and others in Imperial Japan who felt the same way.

A bar of steelit is only smoke at the heart of it, smoke and the blood of a man... smoke and blood is the mix of steel.

CARL SANDBURG

T here are no heroes. You just survive.

SERGEANT STEVE MAHARIDGE, USMC

T he battle for Okinawa in World War II began on April 1, 1945. In the ensuing eighty-two days, an estimated 150,000 civilians would die along with some 110,000 Japanese and 12,520 American soldiers. The Americans called it Operation Iceberg. The Japanese called it tetsu no bofu, the violent wind of steel.

CONTENTS

Dale

To me it was a state of confusion and FEAR with shouted hysterical commands, screaming, shells exploding, darkness and flame from flares and fire. I was there and I never saw the enemy but knew he was out there somewhere. Trying to kill us. I did not know what day it was, how high Sugar Loaf was, the caliber of artillery, the battle planwhich I knew was insane even as a PFCregardless of what the asshole generals on both sides believed they knew from military school.

I fired at this dark hill that was scorched and smoking without having a target in my sights. I was a fucking sharpshooter who shot at rocks.

DaleI hope you are still writing that same book that you talked aboutsomething that has never been done before. Remember?

When your father and I, and the other kids walked, crawled and stumbled down from Sugar Loaf with wounded minds that probably never healed we did not know whether the cause was artillery blast or mortar shells. We were reduced to the point of insanity from the general horror and fear of Fucking war... Slobbering, crying, shaking, vomiting, pissing and shitting your pants, screaming, mumbling, trembling, swearing, FEAR FEAR FEAR FUCKING FEARcombat fatigue my ass.

Fuck the deadlines and publishers demands, write a book that Steve and the rest those wounded guys now gone would be proud of.

Joe

e-mail from Joe Lanciotti, eighty-six years old, February 6, 2012

S omething was wrong in our house. My father had a depth of rage. The majority of the time he was a great dad. Then something would snap, and he temporarily became the worst. He was consumed by an anger that seemed at the edge of violence, but he always pulled back, except for one day in 1960, when he struck my mother. There was blood on the black and white wool wall-to-wall carpet at the base of the stairs. The domestic battle continued behind the closed bathroom door as our mother bandaged herself to stop the bleeding of her temple. The image of that ugly splotch coagulating on the carpet remained in my nightmares for years. Decades later Mom told me that she issued an ultimatumshed walk if that ever again happened.

Dad never again hit her. Yet the rage remained. It was never really targeted at us. It seemed to be focused on some unseen entity.

When I study my baby pictures, taken by my father with an Argus C3 camera, I smile in every frame. As a toddler, I grin ear to ear bundled up and wearing a wool cap while playing next to my sister in our side yard on an Ohio winter day. I was clearly a happy kid. In later picturesage eight, nine, tenhowever, Im frowning, intense. My fathers rage had become my own.

Dad seldom talked about the war. I learned pieces about it beginning when I neared puberty. Dad disclosed things when he and I were alone, usually in his basement shop, where he had a side business grinding industrial cutting tools. I knew instinctively never to ask questions. I just listened. I never broke this unspoken rule.

The war was always present in the form of a picture of my father and another man that Dad had set, at adult-eye level, atop the gas meter next to the machine where he most often worked. It clearly meant a lot to him. Dad once mentioned that it was taken on Guadalcanal. Except for one other time, he said nothing else about it. I became obsessed with the image. The picture came to represent everything that I didnt know about my father and the war, his rage that sometimes caused him to scream, and it was a great gnawing mystery as I grew up.

When my father died in 2000, the picture remained an enigma. Thats when I began a quest to locate men who were with Dad in L Company, Love Company in the military jargon of the era. Love Company, part of the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, Sixth Marine Division, fought in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

Over the course of twelve years I spent ceaseless hours making hundreds of phone calls; I sent out hundreds of letters. Many men had common namesyou cant begin to comprehend how many Robert Harrisons and A. Robertsons that I telephoned, all false leads. And there were those with complex names who appeared to have simply vanished. (A startling number died between 1946 and 1950, and though the database that I used to find their records didnt give causes of death, Id learn that many drank themselves into early graves.) I got hold of sobbing widows, children who were more troubled than I was by their late fathers war experience.

Next page