A searing, lyric voyage through a COVID-stricken America that is also a self-portrait of Maharidges own earlier life as a blue collar writer. In the strange present, we travel with him to homeless encampments and meatpacking facilities, seeing up close all the deprecations of Trumps America and how they echo our countrys melancholy past.

Alissa Quart, author of Squeezed: Why Our Families Cant Afford America

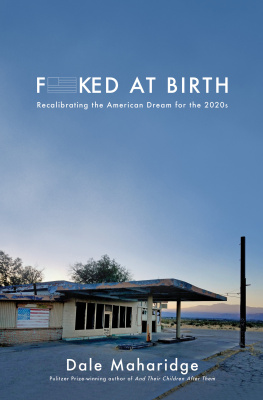

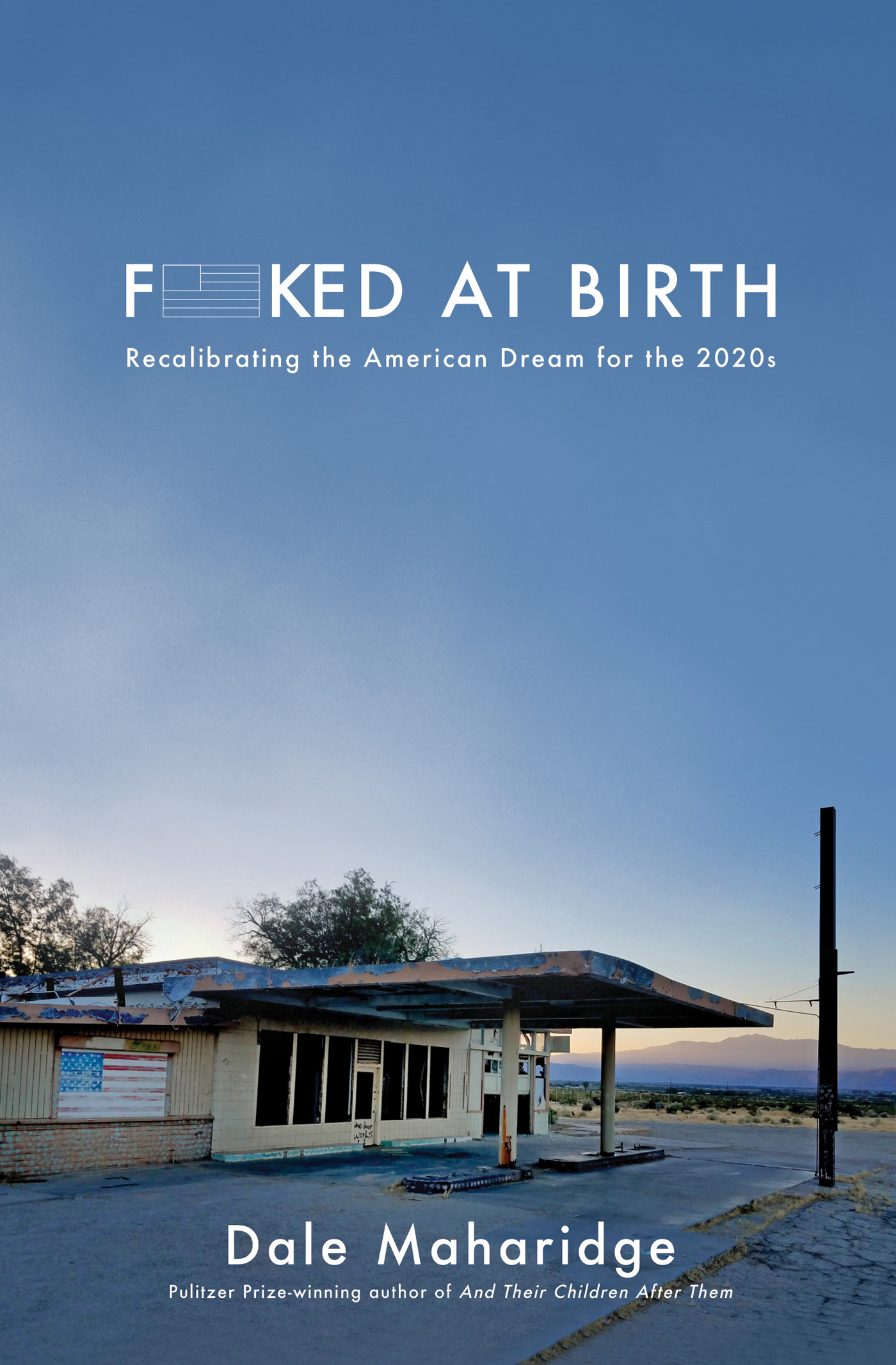

P overty is both reality and destiny for increasing numbers of people in the 2020s and, as Maharidge discovers spray-painted inside an abandoned gas station in the California desert, it is a fate often handed down from birth. Motivated by this haunting phraseFucked at BirthMaharidge explores the realities of being poor in America in the coming decade, as pandemic, economic crisis and social revolution up-end the country.

Part raw memoir, part dogged, investigative journalism, and featuring photos from across the US, Fucked At Birth channels the history of poverty in America to help inform the voices Maharidge encounters daily. In an unprecedented time of social activism amid economic crisis, when voices everywhere are rising up for change, Maharidges journey channels the spirits of George Orwell and James Agee, raising questions about class, privilege, and the very concept of upward mobility, while serving as a final call to action.

From Sacramento to Denver, Youngstown to New York City, Fucked At Birth dares readers to see themselves in those suffering most, and to finallyafter decades of refusalrecalibrate what we are going to do about it.

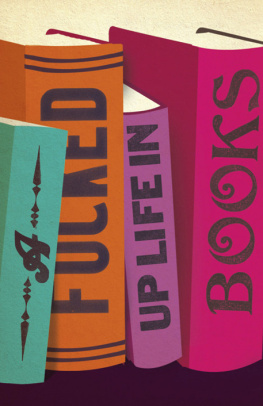

Fucked at Birth

Recalibrating the American Dream for the 2020s

Dale Maharidge

AN UNNAMED PRESS BOOK

Copyright 2020 Dale Maharidge

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. Permissions inquiries may be directed to . Published in North America by the Unnamed Press.

www.unnamedpress.com

Unnamed Press, and the colophon, are registered trademarks of Unnamed Media LLC.

ISBN: 978-1951213220

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Maharidge, Dale, author.

Title: Fucked at birth : recalibrating the American dream for the 2020s / Dale Maharidge.

Description: First edition. | Los Angeles, CA : The Unnamed Press, [2020] |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020042635 (print) I LCCN 2020042636 (ebook) I ISBN 9781951213220 (trade paperback) I ISBN 9781951213237 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: PoorUnited StatesSocial conditions21st century. | PoorUnited StatesHistory. | American Dream. | United StatesSocial conditions21st century. | United StatesEconomic conditions21st century.

Classification: LCC HC110.P6 M275 2020 (print) I LCC HC110.P6 (ebook) I DDC 305.5/690973dc23

LC record available athttps://lccn.loc.gov/2020042635

LCebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020042636

This book is a work of nonfiction.

Cover Photgraph by Dale Maharidge

Designed and Typeset by Jaya Nicely

Manufactured in the United States of America by Versa Press, Inc.

Distributed by Publishers Group West

First Edition

Portions of this book first appeared in the Nation magazine; The Coming White Minority: California, Multiculturalism, and the Nations Future, by Dale Maharidge (Vintage Books); Someplace Like America: Tales from the New Great Depression, by Dale Maharidge and Michael S. Williamson (University of California Press); The Sacramento Bee; The New York Times. All photographs courtesy of the author with the exception of Terrance Roberts, photos courtesy of pp. 98-99; p. 125, courtesy of Nathan Mahrt; p.30 by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USF34-009916-E. Funding was provided by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

CONTENTS

For Joanne

Fucked at Birth

FUCKED AT BIRTH

From March through June of that darkest of yearsmore bleak than my youth of 1968, when Bobby and Martin and so many dreams diedI was living in Southern California near the beach. We all have our pandemic stories. Mine was quite uncommon in that I was one of those relatively few Americans afforded the luxury of working from home on Zoom. I didnt have to gig hustle for Uber, Lyft, or DoorDash, or drive for FedEx, Amazon, or UPSor worse, pray that my job came back after the temporary assistance ran out. We with white-collar employment make the assumption that a majority of Americans are exactly like us because most of us never interact with the working class. A friend who was well intentioned, yet clueless as to how most of the three hundred million or so of our fellow citizens live, suggested that to survive a crisis such as Covid-19, Americans should have $5,000 cash on hand, or double that amount if our budgets could afford it. A year before she uttered these words to a journalist for a major publication, the Fed reported that, in the best economy in postwar history, four out of ten Americans did not have enough money in the bank to pay an unexpected expenditure of $400.19.

I was in New York City earlier that year, teaching my classes. In late February, Id fallen illthere were intense headaches and I was sleeping long, fitful hoursthen it became difficult to sit in a chair. My lower back hurt. I assumed I had pulled something, but later suspected it was a kidney infection. Id been around two sick people. I didnt believe that it was the novel coronavirus because federal officials asserted that it was not yet in the United States. (Much later, in California, when I had an antibody test, the first one showed that I was possibly positive but a second came back negative. The test cost $50. Most of the dozens then being peddled were unreliable.) I told myself I had it. But maybe I didnt.

We were without national leadership. It was the quintessential American story: we were left to fend for ourselves. We were told masks were worthless. Then we were told they were necessary. In Manhattan, store shelves were stripped of hand sanitizer and alcohol. In high school my friends and I found a way to purchase 190-proof Everclear. Our motto: Things are never clear with Everclear. Was it still sold? I found the last two flasks available at a liquor store on Broadway and thereafter reflexively doused my hands from a small yellow spray bottle of it that I carried everywhere.

After recovering from the illness, I chose to remain in the city, even after we were compelled to switch to online teaching. The streets were largely deserted. The panhandlers remained visible. A legless beggar without a wheelchair always sat on the sidewalk at the West Side Market near my apartment, his hand out. With far fewer customers emerging, this man grew desperate. He now lunged, crawling toward me like a skittering crab, propelling himself with the stumps of his legs and one arm, the other arm outstretched, palm extended; his eyes were feral and pleading, and from his gaping mouth hung a sliver of drool. The next evening I was at JFK, sending pictures of the unpeopled JetBlue terminal to friends. On a call to one of them I resorted to clich: Its a scene out of a zombie apocalypse film. Or was it simply reality? There were twenty-eight people on the flight to California.

For the next two months I isolated with friends, working in a cottage in their backyard. We kept to ourselves like many white-collar Americans. We watched from the window as the delivery drivers from Amazon, UPS, and FedEx left a steady flow of boxes on the front porch. We did not interact with them.

Next page