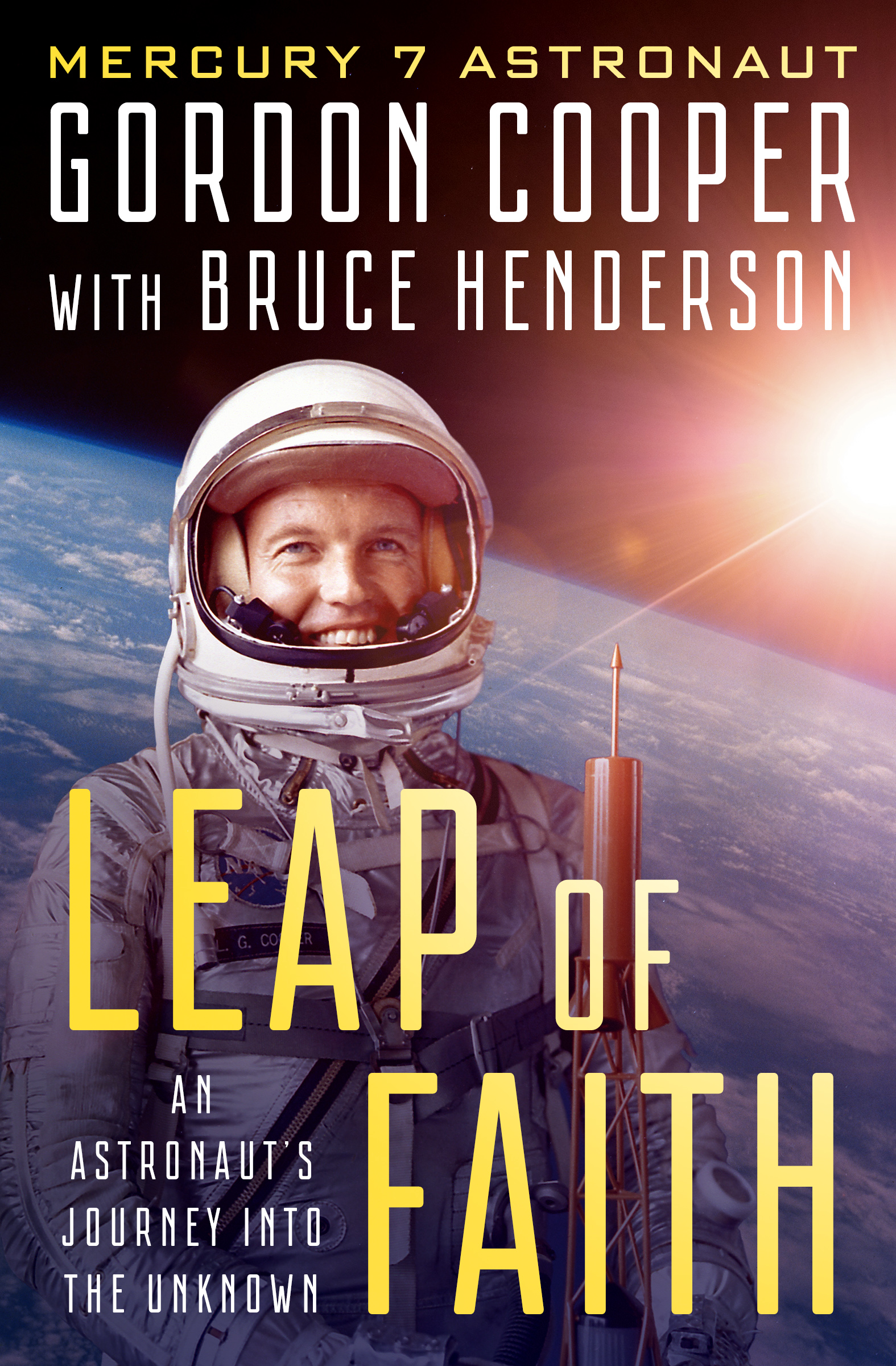

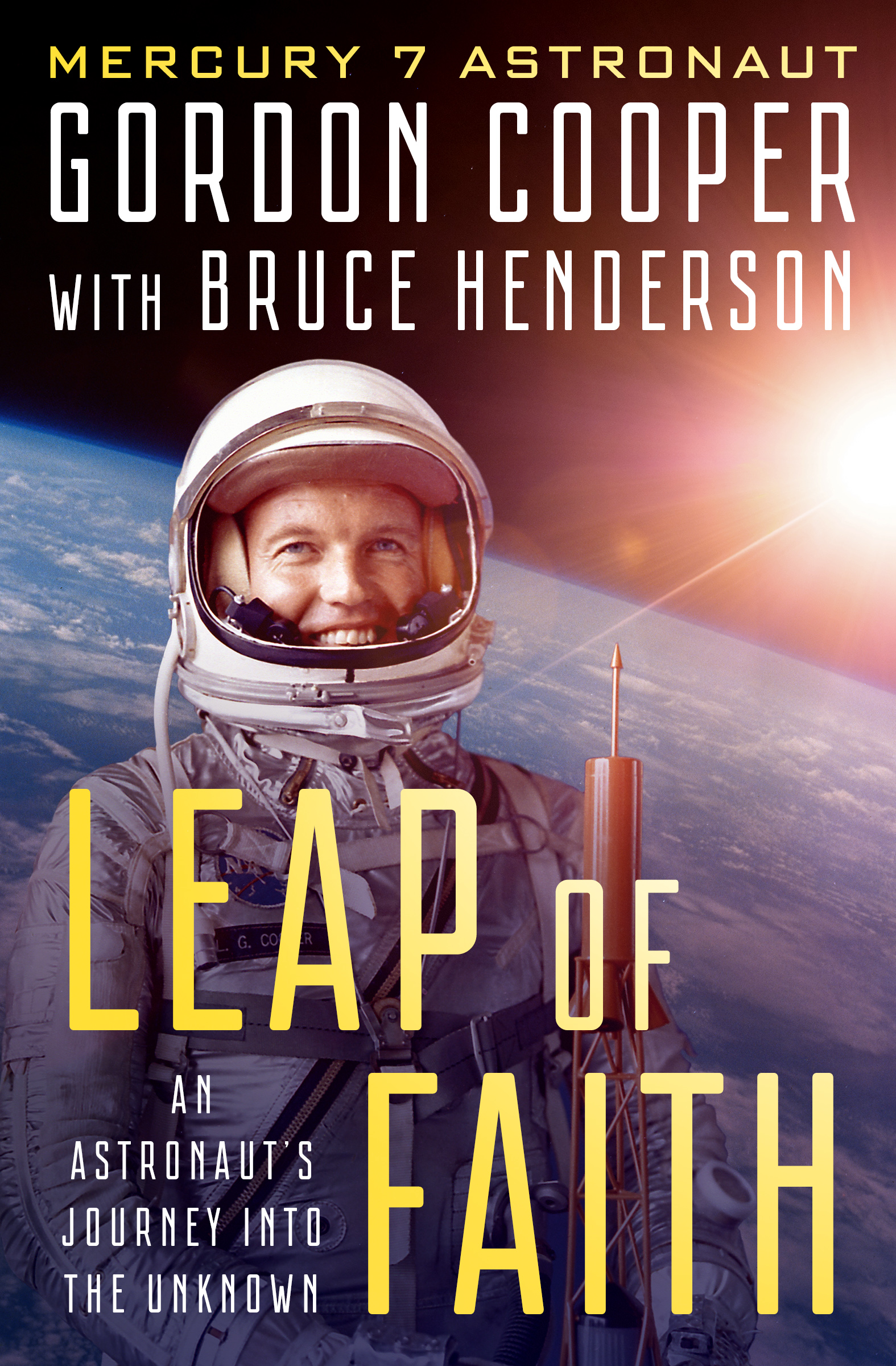

Leap of Faith

An Astronauts Journey Into the Unknown

Gordon Cooper with Bruce Henderson

For my wife, Suzan,

who has put up with a lot through the years

from this scruffy old fighter pilot

PROLOGUE

May 15, 1963

Cape Canaveral

They woke me up at three in the morning, in the dark.

I had been up late the night before, hitting the sack not much before eleven oclock in Hangar S, the astronaut headquarters at the Cape. The hangar had been remodeled inside to accommodate our various types of training apparatus, a pressure chamber, living quarters and a dining room, a medical suite, a ready room, and everything else we needed to prepare for a mission. It was also here that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had offices and where our spacecraft were constantly worked on by engineers and technicians.

I showered, then enjoyed a going away breakfast of fresh-squeezed orange juice, filet mignon, scrambled eggs, toast, grape jelly, and coffee, with some of the key people on the team, including the flight surgeon and a few fellow astronauts who, through their good-natured ribbing, were determined to see that I stayed loose.

From there, I went down the hall to the suiting-up rooma sterile space off-limits to bugs, dirt, debris, and anything else we didnt want to take along into space. Everyone working in here was dressed in a white smock and white hat and wore disposable paper covers over their footwear.

I stripped, and a medical technician glued a half-dozen medical sensors to various spots on my body that hed first sandpapered and scrubbed with alcohol. I donned long underwear and was helped into my bulky flight pressure suit.

I took the seven-mile trip to pad 14 in the back of a NASA van.

I much preferred the way I had arrived at the pad for final hot tests of all systems several days earlier: at the wheel of my new 300-horsepower blue Corvette, which I had purchasedthe same way other astronauts purchased their Vetsat a 50 percent discount from General Motors through its Brass Hat program for employees and a limited number of VIPs. That day I had successfully lobbied my NASA bosses to let me drive myself to the pad on the promise that Id be careful. I hadnt even bothered to ask this morning, knowing what the answer would be.

My rocket awaited me: Atlas booster number 130D, more than ten stories tall. It stood in the pitch dark like a lone sentry, eerily bathed in columns of white light thrown skyward by huge spotlights.

The first time I had seen an Atlas launch was three years earlier, only a few months after seven of us had been selected for Project Mercury as Americas first astronauts. They took us down to the Cape for a launch. We stood as a group outside in the humid nightthe Mercury Seven, as we became knownflat-topped fighter jocks in short-sleeved shirts, buoyant and more than a tad cocky, as all good fighter pilots must be. We came to be referred to on in-house memos as CCGGSSS, as our names were always listed in alphabetical order: Carpenter, Cooper, Glenn, Grissom, Schirra, Shepard, Slayton.

We were there to see a test of the Atlas, the newly built rocket that was expected to carry us into orbit in the years to come. We watched the huge rocket rise slowly off the pad on three thick columns of flame. It was a thunderous start, and the ground rumbled beneath our feet. The rocket flew straight up for forty or fifty seconds and was almost directly overhead as it slowly began to nose over on its long arcing flight toward the horizon. Several hundred VIPs were in attendance, including many congressmen and several committee chairmen who were instrumental in providing funding for the space program. We all stood there, craning our necks to keep our eyes on the magnificent silver bird, when suddenly the sky erupted in a tremendous kaboom! and the rocket blew up in a jillion flaming pieces. While some spectators ducked instinctively, the burning debris would be carried by the rockets momentum out over the ocean and drop into the drink several miles offshore.

We looked at each other. Thats our ride? someone deadpanned.

Two months later there had been another cataclysmic failure, and in the months that followed, more failed attempts.

In late 1960 NASA put on another public show designed to prove that the Mercury spacecraft and the smaller Redstone rocket, which would be used for two planned suborbital flights, were ready for upcoming manned missions. These flights would not go high or fast enough to reach orbit but would simply slingshot the spacecraft one hundred miles high, where space officially beginssome fifty miles above the Earths atmosphereand downrange three hundred miles at five thousand miles per hour for an ocean landing near Bermuda. For the event, NASA brought the seven of us back, along with hundreds of VIPs. This time, as the flames burst from the rocket, it lifted off only two inches before the engines mysteriously cut off and the rocket settled back onto the pad. All was quiet. However, the signal for liftoff had already been sent to the automatic sequencer. About sixty seconds lateras called for by the flight planthe spacecrafts escape tower, designed to pull the capsule and its occupant to safety in the event of a problem in the first minute after liftoff, separated from the spacecraft and shot into the sky like a spear. As the crowd silently watched the only thing moving out there that day, the escape tower went up about four thousand feet, then came back down, driving itself into the ground about a hundred yards away.

As for the Atlas, before John Glenns orbital mission in 1962the first manned mission to use the powerful new rocketthere had been a total of thirteen blowups, some on the launch pad and others as the Atlas climbed into the sky. Test pilots understood the nature of new technologies: going up in hurtling pieces of untested machinery and putting our hides on the line. We knew about hanging it over the edge and pushing back the envelope, then hauling it back in and doing it again tomorrow. When the time came, each of us would take his turn sitting atop the same type of rocket wed seen blown to smithereens before our eyes. We did so not because we were suicidal or crazed but because we were pilots.

Early on in the space program there had been quite a debate over whether the manned launches should be covered on live television or a taped and edited version offered to the public later. Live TV would reveal anything and everything that went wrong; in the event of a tragic failure, public sentiment could turn against the program. I suppose we could have tried to do what the Soviets didhide our failures and trumpet our successesbut could a free country really do that? We were the representatives of an open society, and we would take our chances in full view of the worldon live television.

Up the gantry elevator I went on launch morning, carrying the suitcaselike portable cooler that kept me supplied with oxygen until I could be connected to the spacecrafts system. At the top I was greeted by Guenter Wendt, who in his clean room attire of white overalls and white sandwich hat looked like the neighborhood ice cream man but who was one of the brilliant German rocket scientists helping the United States in the space race with the Russians, who also had German rocket men assisting them.

Next page