I WAS TEN WHEN my father died, and before that moment, that slap of silence that reset the clock, I cant remember much. There are some things, of coursefractals, shards of memory, sharp as broken glass. I remember an old globe that sat on the table by my bed. I must have been five or six. It was a present from my mother, whod received it from the author Isak Dinesen, long after shed written Out of Africa .

When I couldnt sleep, Id touch the globe, trace the contours of continents in the dark. Some nights my small fingers would hike the ridges of Everest, or struggle to reach the summit of Kilimanjaro. Many times, I rounded the Horn of Africa, more than once my ship foundering on rocks off the Cape of Good Hope. The globe was covered with names of nations that no longer exist: Tanganyika, Siam, the Belgian Congo, Ceylon. I dreamed of traveling to them all.

I didnt know who Isak Dinesen was, but Id seen her photograph in a delicate gold frame in my mothers bedroom: her face hidden by a hunters hat, an Afghan hound crouching by her side. To me she was a mysterious figure from my mothers past, just one of many.

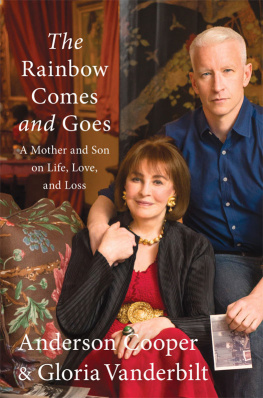

My mothers name is Gloria Vanderbilt, and long before I ever got into the news business, she was making headlines. She was born in 1924 to a family of great wealth, and early on discovered its limits. When she was fifteen months old her father died, and for years afterward, she was shuttled about from continent to continent, her mother always moving off into unseen rooms, preparing for parties and evenings on the town. At ten my mother became the center of a highly publicized custody battle. My mothers powerful aunt Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was able to convince a New York court that my mothers mother was unfit. It was during the Depression, and the trial was a tabloid obsession. The court took my mother away from her mother and the Irish nurse she truly loved, and handed her over to Whitney who soon sent her away to boarding school.

My brother and I knew none of this as children, of course, but wed sometimes seen a look in our mothers eyes, a slight dilation of the pupil, a hint of pain and fear. I didnt know what it meant until after my father died. I glanced at myself in the mirror and saw the same look staring back at me.

AS A BOY looking at that globe, I grew up believing, as most people do, that the earth is round. Smoothed like a stone by thousands of years of evolution and revolution. Whittled by time. Scraped by space. I thought that all the nations and oceans, the rivers and valleys, were already mapped out, named, explored. But in truth, the world is constantly shifting: shape and size, location in space. Its got edges and chasms, too many to count. They open up, close, reappear somewhere else. Geologists may have mapped out the planets tectonic plateshidden shelves of rock that grind, one against the other, forming mountains, creating continentsbut they cant plot the fault lines that run through our heads, divide our hearts.

The map of the world is always changing; sometimes it happens overnight. All it takes is the blink of an eye, the squeeze of a trigger, a sudden gust of wind. Wake up and your life is perched on a precipice; fall asleep, it swallows you whole.

None of us likes to believe our lives are so precarious. In 2005, however, we were reminded just how quickly things can change. The year began with the tsunami and came to a close with Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. There were wars and famine, and other disasters, natural and man-made.

As a correspondent and anchor for CNN, I spent much of 2005 reporting from the front lines in Sri Lanka and New Orleans, Africa and Iraq. This book is about what I saw and experienced, and how it crystallized much of what Id previously learned and lived through in conflicts and countries long since forgotten.

For years I tried to compartmentalize my life, distance myself from the world I was reporting on. This year, however, I realized that that is not possible. In the midst of tragedy, the memories of moments, forgotten feelings, began to feed off one another. I came to see how woven together these disparate fragments really are: past and present, personal and professional, they shift back and forth again and again. Everyone is connected by the same strands of DNA.

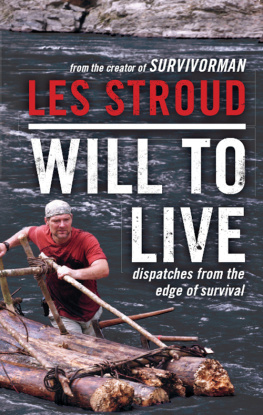

Ive been a journalist for fifteen years now, and have reported on some of the worst situations on earth: Somalia, Rwanda, Bosnia, Iraq. Ive seen more dead bodies than I can count, more horror and hatred than I can remember, yet Im still surprised by what I discover in the far reaches of our planet, the truths revealed in the dwindling light of day, when everything else has been stripped away, exposed, raw as a gutted shark on a fishermans pier. The farther you go, however, the harder it is to return. The world has many edges, and its very easy to fall off.

THE WEEK AFTER my father died, I saw one of those old Jacques Cousteau documentaries. It was about sharks. I learned that they have to keep moving in order to live. Its the only way they can breathe. Forward motion, constantly forcing water through their gills. I wanted to live on the Calypso, be part of Cousteaus red-capped crew. I imagined myself swimming slowly alongside a Great White, my hand resting lightly on its cold, silver steel skin. I used to dream of its sleek torpedo body silently swaying through pitch black seas, never resting, always in motion. Some nights I still do.

Hurtling across oceans, from one conflict to the next, one disaster to another, I sometimes believe its motion that keeps me alive as well. I hit the ground running: truck gassed up, camera rollinglocked and loaded, ready to rock, as a soldier in Iraq once said to me. Theres nothing like that feeling. Your truck screeches to a halt, you leap out, the camera resting on the space between your shoulder and neck. You run toward what everyone else is running from, believing your camera will somehow protect you, not really caring if it doesnt. All you want to do is get it, feel it, be in it. The images frame themselves sometimes, the action flows right through you. Keep moving, keep cool, stay alive, force air through your lungs, oxygen into your blood. Keep moving. Keep cool. Stay alive.

I didnt always feel this way. When I started reporting I was twenty-four, and didnt mind waiting for weeks in dingy African hotels. I was on my own with just a home video camera and a fake press pass. I wanted to be a war correspondent but couldnt get a job. In Nairobi, I practically moved into the Ambassadeur Hotel. It was across the street from the Hilton, but a world away. During the day, the second-floor lounge filled with evangelical Christians singing, Jesus, God is very, very wonderful, while outside, on the street, a man with shiny, steel hooks for hands and pale plastic prostheses for arms waved wildly in the air screaming passages from the Old Testament. At night, the bar opened, and sweating waiters in red jackets served tall glasses of Tusker beer, weaving between black businessmen and prostitutes in shiny emerald dresses. I was alone and lost, clinging to a routine. Lunch at noon. Dinner at six. Weeks passed, and I just waited.

By the time I was twenty-five, it had all changed. I had a job, a salary. I was being paid to go to wars. It had taken me nearly a year of shooting stories, and of hard travel, but I was finally a foreign correspondent. The more I saw, however, the more I needed to see. I tried to settle down back home in Los Angeles, but I missed that feeling, that rush. I went to see a doctor about it. He told me I should slow down for a while, take a break. I just nodded and left, booked a flight out that day. It didnt seem possible to stop.