Copyright 2016 by Walter R. Borneman

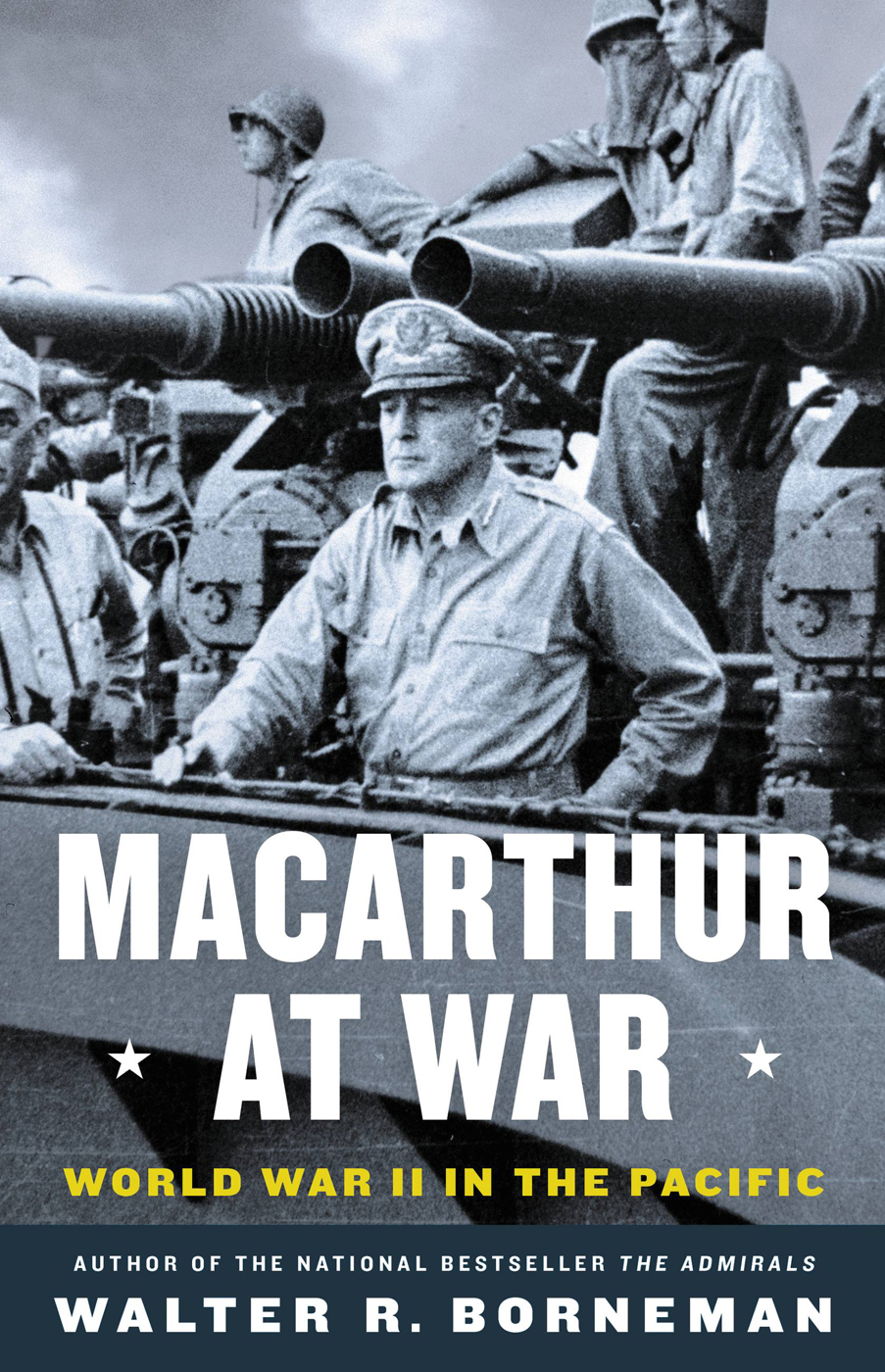

Cover photograph courtesy of the National Archives, photo no. 111-SC-188839

Author photograph by Fall River Productions, Inc.

Cover 2016 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

American Spring: Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution

The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy, and KingThe Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea

Iron Horses: Americas Race to Bring the Railroads West

Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America

The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America

14,000 Feet: A Celebration of Colorados Highest Mountains

(with Todd Caudle)

1812: The War That Forged a Nation

Alaska: Saga of a Bold Land

A Climbing Guide to Colorados Fourteeners

(with Lyndon J. Lampert)

For Paul L. Miles, PhD, Colonel, USA, Ret.,

soldier, scholar, and friend,

and

for the memory of my father,

who embarked at the age of nineteen to fight in MacArthurs war

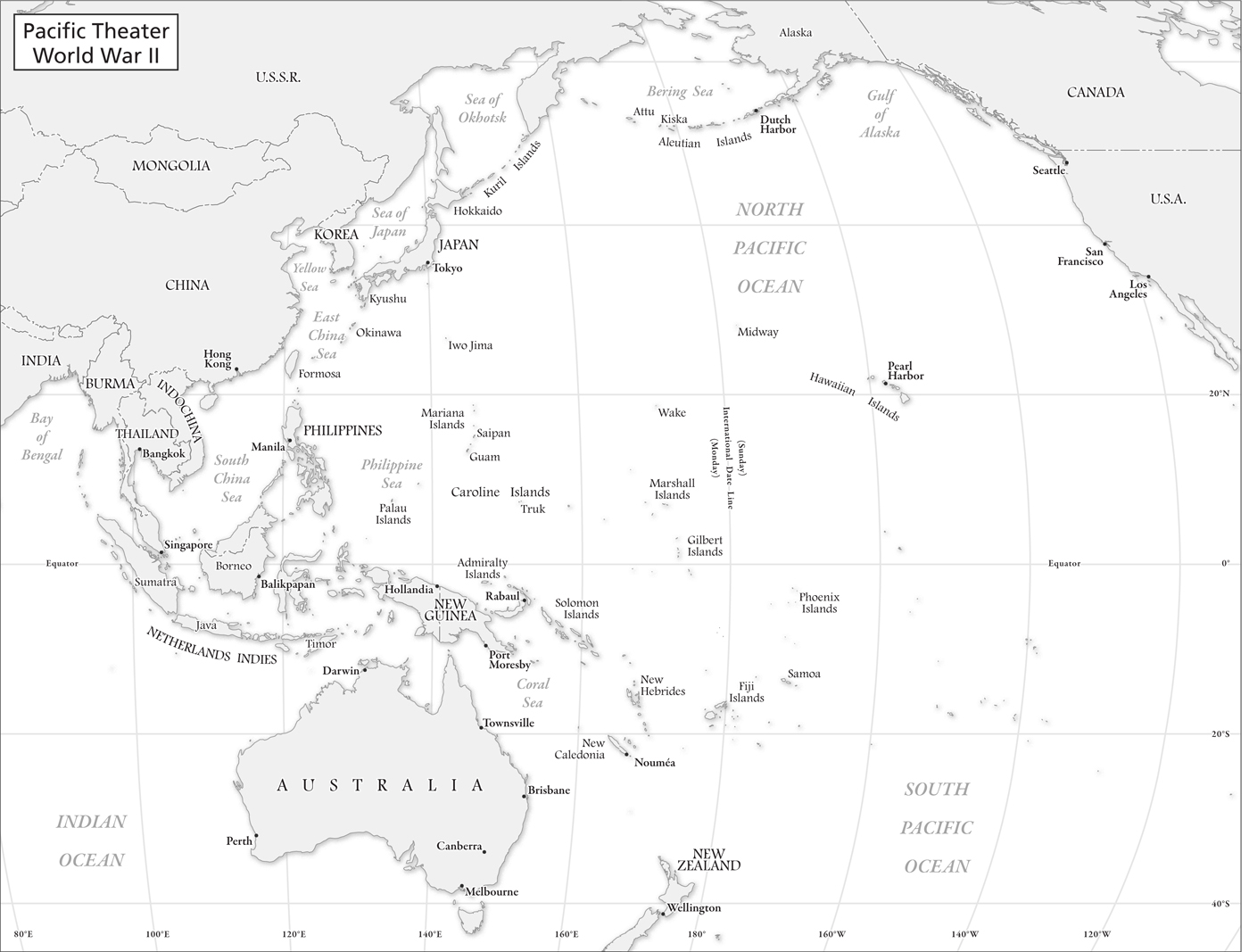

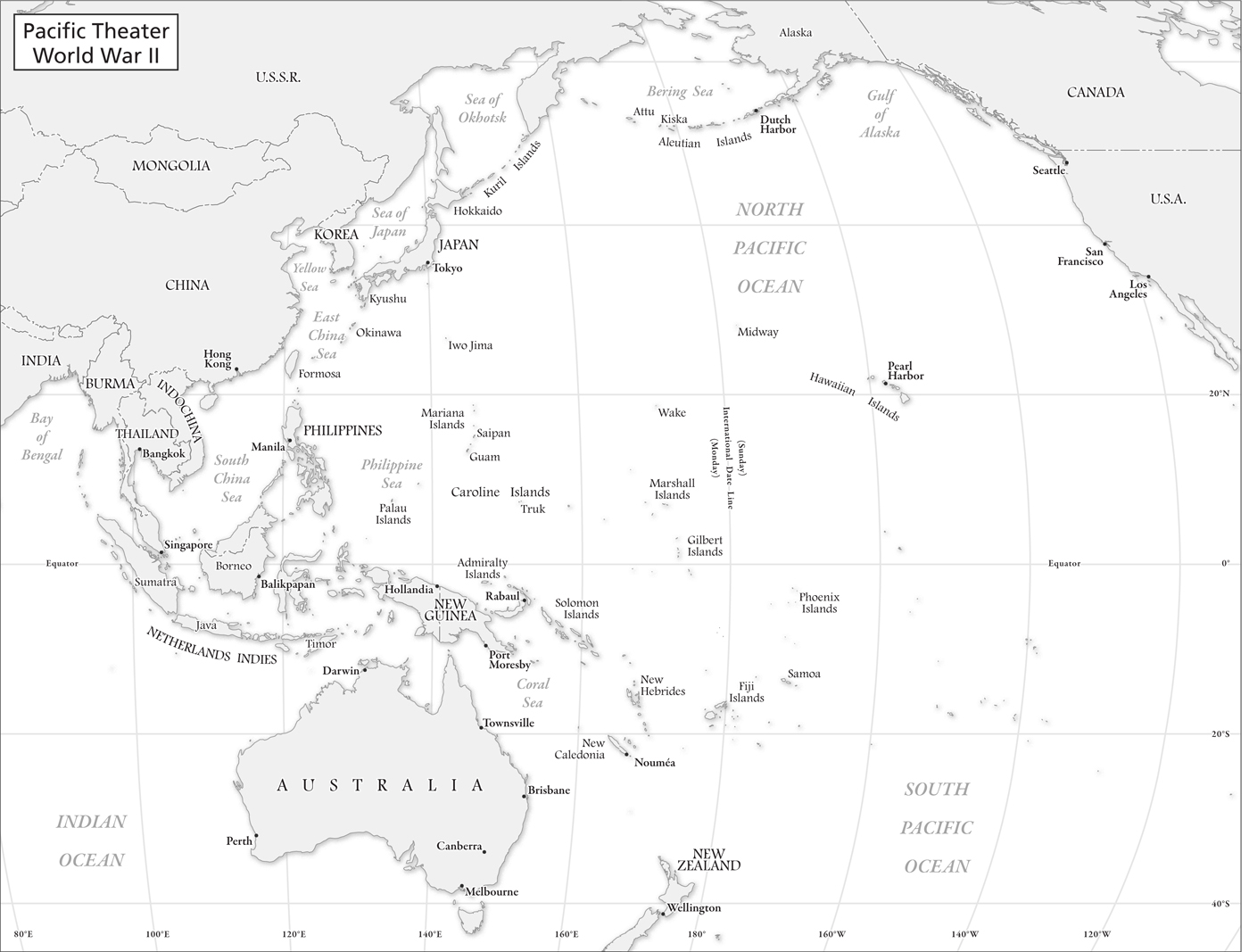

| Pacific Theater, World War II |

| The Philippines, 1941 |

| Luzon, December 1941 |

| Bataan, January 1942 |

| MacArthurs Escape, March 1942 |

| Pacific Commands, 1942 |

| Battle of the Coral Sea, May 1942 |

| Japanese Advances, 1942 |

| Across the Owen Stanley Range, 1942 |

| Battle of the Bismarck Sea, March 1943 |

| Northeast New Guinea, 1943 |

| Admiralties Invasion, March 1944 |

| Leap to Hollandia, April 1944 |

| Biak-Morotai-Palau, September 1944 |

| Battle of Leyte, October 1944 |

| Operations on Luzon, Early 1945 |

| Pacific Operations, 1945 |

I n predawn darkness the black telephone rang loudly. The generals wife lifted the receiver from its cradle on the nightstand in the Manila Hotel penthouse suites master bedroom and hesitantly answered it. Telephone calls in the middle of the night were rarely a good thing. The caller identified himself and said he must speak to the general. She passed the receiver to her husband. Yes? he answered as if on duty, which indeed he always was. His face grew increasingly taut and his jaw set as he heard his chief of staffs report. Only then did he show surprise. Pearl Harbor? Douglas MacArthur asked incredulously. It should be our strongest position.

Five thousand miles to the east, across the international date line, it was still December 7 over Hawaii, and hundreds of planes from six Japanese aircraft carriers had just rained destruction on the battleships of the Pacific Fleet. Deployed to Pearl Harbor to bolster American influence and response throughout the Pacific, they had become the target of a devious surprise attack. Suddenly the United States was at war.

In many respects Douglas MacArthur had been preparing for this moment his entire life. First and foremost, he was the consummate soldier, a staunch defender of his country and its honor. But around that core conviction was a complex personality. There was never any middle ground with Douglas MacArthur. He was a study in contradictions, capable of inspiring the very best in some men but also opening himself to ridicule and even inspiring hatred in others.

One either swore by MacArthur or despised him, and MacArthur himself was largely responsible for eliciting those extremes of emotion. He could be competent, caring, and visionarya leaders leaderbut he could also be vain, manipulative, and deceitful, the ultimate backstabber. The only beliefs about which he did not equivocate were his personal sense of mission for the United States and his guiding principles of duty, honor, and country. Always, in his mind, it came back to duty, honor, and country.

As the telephone rang that night, he was about to turn sixty-two years of agerelatively old for the time and just two years shy of the armys mandatory retirement age. One could not tell that by looking at him, however, or by listening to him. His attention to detail was legendary and his memory razor sharpnot just for his own experiences and the grand sweep of history but also for the minutiae of command structures and deployments around the region, those of friend and foe alike. Physically, he was still quite robust, the result of a passion for athletics in his younger days, when what he lacked in raw talent he made up for with gritty determination. His daily exercise regimen still included walkseven if only pacing in his office or on the wide terrace of the penthouseand a morning set of calisthenics.

In the time-honored fashion of most warriors, MacArthur claimed to eschew electoral politics and know nothing of them, but behind that veneer of feigned innocence he was adroit at political persuasion and theater. Conservatives had floated his name for the presidency in 1940, but that was mostly indicative of the dearth of credible opponents to Franklin Roosevelt.

Indeed, MacArthur and FDR were of similar ilk in more than one significant way: they were sure of themselves and in control even in the face of defeat and error. Roosevelt was a gentleman politician; MacArthur a gentleman soldier. Yet a complete analysis of Douglas MacArthurs character, as well as his effectiveness as a leader, would have been decidedly premature on that December morning in the Philippines. MacArthur was still a military officer of only limited renown. He had shown bravery and competence in the trenches of France during World War I and breathed new life into a beleaguered West Point afterward, but beyond his rise to army chief of staff at a young age, there was little about MacArthurs career to recommend it to a place of highest honor in history books.