CONTENTS

PART THREE: LATE WAR STORIES (19441945)

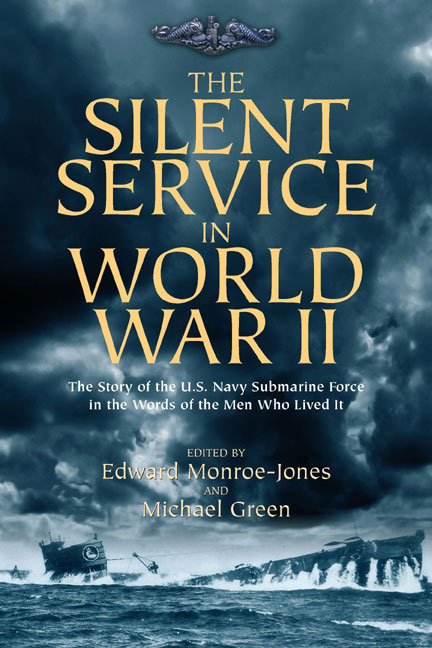

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2012 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford, OX1 2EW

Copyright 2012 Edward Monroe Jones and Michael Green

ISBN 978-1-61200-125-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-137-1

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and

the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or

by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any infor

mation storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea 2012 by Ernest J. Zellmer, used by permission.

Many of the stories in this book were originally published by Polaris Magazine and Submarine

Journal. Others were previously published in the book Steep Angles, Deep Dives. These stories

are used by permission of their respective copyright holders.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

E-mail:

INTRODUCTION

O n December 7, 1941, the day that Japanese aircraft bombed Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy had 111 submarines, but they were a collection of First World War type boats, several one-of-a-kind boats, mine layers, and a few newer Gato-class fleet-type submarines. The older boats were 0, R, and S-class boats. America had seen the World War II approaching and had accelerated its submarine building program. By December, 1941 there were 73 fleet-type boats being built.

While the European war against Nazi Germany absorbed a good share of the Navys ships, submarines were given the primary task of bringing the war to Japan in the Pacific. The old 0-boats were used for training purposes at the submarine training facility in New London, Connecticut and the R-boats were assigned to Key West, Florida where they provided services for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) destroyers. Some of these boats were also assigned to the Navys Coco Solo submarine base on the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal.

S-type submarines and fleet-type submarines had been assigned to the Navys Pacific bases including Pearl Harbor and Manila/Cavite in the Philippines. Following Pearl Harbor when it became obvious that the United States would not be able to prevent the Japanese from taking Manila/Cavite, Commander, Submarines Pacific (ComSubPac) who worked for Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet (CincPacFleet) began the process of establishing submarine bases in Australia. The two primary bases were at Perth/Fremantle on the west coast and Brisbane on the east coast.

The narratives contained herein are primarily by men who served on S and fleet-type boats. As submarines tend to be somewhat complicated creatures a short explanation of the S and fleet-type submarines may assist readers in visualizing the action.

The S-series of American submarines were small. They displaced between eight hundred and nine hundred tons. By todays standards they amounted to little more than toys, but to the men who sailed them the Sboats were a source of remorseless problems and sluggish solutions. They were about 240 feet in length and had a 200 foot test depth. This was the maximum depth that designers estimated a submarine could descend before its hull collapsed. The truth was that many S-boats had riveted hulls that had become so eroded by age that they were confined to depths of under 100 feet. Although S-boats varied somewhat in length and equipment they generally had a single hull. This meant that ballast tanks were internal. Electric Boat Company had a patent on the U-shaped internal ballast tank and championed the superior performance of these tanks. Portsmouth Naval Shipyard installed saddle tanks that wrapped around the pressure hull, but they were partial and extended above the water line. Having tanks above the water line resulted in slower dives, definitely a problem in combat conditions.

Both fuel ballast tanks and main ballast tanks had flood valves called Kingston valves that were operated from levers on the starboard side of the control room. The range of the S-boats was so limited and the de mands made on the boats were so great that many captains used all of the tanks as fuel ballast tanks. Of course, this reduced the freeboard and made cruising in heavy seas dangerous.

S-boats generally had five compartments: a torpedo room forward followed by a single battery compartment. Aft of the battery compartment was the control room, which was called the central operating compartment, an engine room, and a motor room. Above the control room was a tiny conning tower. Later S-boats had two battery compartments and were therefore longer. Each compartment was separated by a watertight bulkhead. In most S-boats, however, these bulkheads had not been tested to the two hundred foot test depth of the submarine.

Earlier S-boats had just one battery under the crews and officers berthing. Battery power could be supplied in series for maximum power and in parallel for maximum endurance. Large knife switches in the after part of the battery compartment were handled by electricians who responded to the diving officers shouted orders.

On the early S-boats, the conning towers had little ports and men (it only held two people) in the conning tower could watch the fish. Periscopes extended down into the control room, next to the bow and stern plane wheels. On a few boats a short periscope stopped in the conning tower. In the portside after corner of the control room was the radio room that accommodated the large transmitting and receiving stacks. Communication was by Morse code and the radioman rate was critical to safety. Antennas were primitive, usually a half or quarter wave, end-fed, long line from the shears to the stern.

Passive and active sonar had been developed by other nations in World War I. S-boats could listen on a broadband frequency receivers that were housed in rubber shells called rats in honor of their shape. Another device was the Y-tube that was the fore-runner of more advanced sonar. Boat-to-boat underwater communication was by a Fessenden oscillator. This was a Morse code, keyed transducer that was good for eight miles in ideal conditions and about a half mile in typical underway conditions.

The U.S. Navy could not come up with a reliable submarine engine. Pre-World War I boats had gasoline engines that were undesirable not only because they were dangerous due to the flammability of the fuel, but because of its volatility when fumes from the fuel permeated the boat. The U.S. Navy first went to German made MAN (Mannheimer, Augsburger, Nuern burg) diesel engines and then finally to American made diesel engines. The engine room accommodated two engines, which had clutches and thrust bearings at the rear of the compartment. The clutch levers were thrown by enginemen while the battery-driven motors were operated by the electricians. The propulsion motors were on either side of centerline in the motor room.