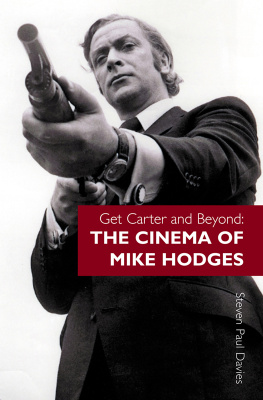

Get Carter and Beyond:

THE CINEMA OF MIKE HODGES

Get Carter and Beyond:

THE CINEMA OF MIKE HODGES

Steven Paul Davies

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The major part of this book comprises interviews recorded with Mike Hodges over the last two years, most conducted at his home in Dorset. Principle thanks, therefore, go to Mike for his willingness and ability to respond incisively and honestly to my continued questioning! His co-operation also extended to providing the numerous behind-the scenes stills that appear throughout the book.

Many thanks also to Clive Owen, George Segal, Michael Caine, John Glen, Alex Cox, Wolfgang Suschitsky, Andrew Pulver at The Guardian and to Paul Mayersberg for his kind interest and support.

Picture Acknowledgements

Get Carter illustrations courtesy of Wolfgang Suschitzky; Dandelion Dead illustrations courtesy of Granada; Croupier illustrations courtesy of Simon Mein/FilmFour. All production stills courtesy of Mike Hodges.

FOREWORD

More than any other form of art, except possibly architecture, filmmaking, the film-makers life work, is about what might have been.

With different actors, or with more money, or at a different time, or with a different promotional campaign, we might have been looking at something other than what we see. This is not what most audiences speculate on, although occasionally critics do, but it is a large preoccupation for the film-maker, before, during and after the making of a film. Steven Paul Davies book on and with Mike Hodges is almost as much about what didnt happen as what did. It could have adopted as a subtitle the title of his 1983 TV film, Missing Pieces.

Few film-makers today are inclined to admit to discontinuity in their work. It would hint at confusion and failure. Samuel Becketts axiom Fail again. Fail better, is not the ideal motto for contemporary celebrity-success. But uncertainty is ever the sleeping partner of ambition.

The narrative here is resolutely chronological. It cannot and will not paper over the life cracks or plane out the art warps. Oddly, the effect of reading the whole book is like hearing a journal of the frustrations and elevations that alternate in the making of a single film. Mikes voice-over throughout makes everything untidily life-like rather than formally art-like. Its more of a character piece than a plot.

It poses the interesting question of how far a mans long-time work reflects his personality and behaviour, especially in such a social form as film where he is not alone. In a glasshouse society where friendship is illusory and agendas are hidden there will inevitably be a preponderance of villains over heroes. Film-life is a devious affair and engenders personal prejudice as a defence. But then what are our prejudices if not the illegitimate children of our convictions?

Mikes best films, The Terminal Man and Black Rainbow, both commercial failures, are about manipulation. But they are not, as films, manipulative. None of their characters invites easy identification. Thank God. They are decidedly other people. An only child myself, I recognise in Mike a similar unsentimental sensibility. A couple of detached sibling-free voyeurs observing what the world does to its unfortunate inhabitants. People like us. A world as Le Corbusier observed, about the nature and purpose of a house, is a machine for living in.

Its unlikely that this book would have been published without the recent success of Croupier. From being written off, Mike is now being written up. And at the age of three score years and ten. Ainsi va le monde. The number 70 reminds me of an occasion when Mike and I were lunching with a sympathetic critic who described Croupier as somehow coming from the Seventies, in which decade he thought it might have fared better. This was a year or more before the US release. It was therefore an unexpected delight that American audiences were completely unaware they were applauding a 30-year-old movie as if it were new: what might not have been, as it were.

PAUL MAYERSBERG

Cannes, June 2002

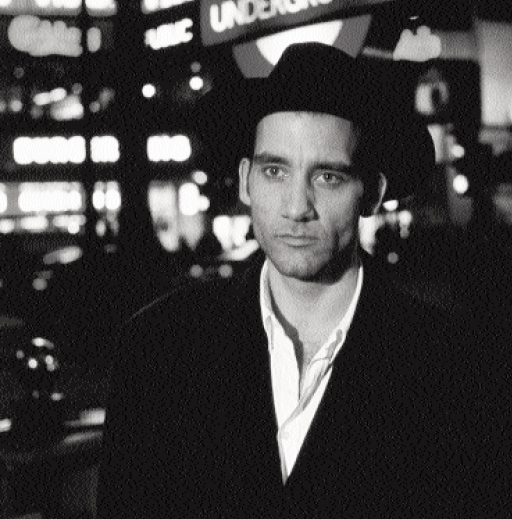

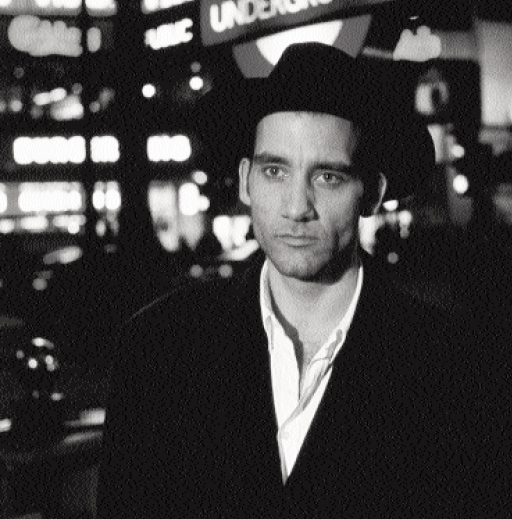

Clive Owen as Jack Manfred in Mike Hodges Croupier (1998)

Introduction

Its all numbers, the croupier thought. The spin of the wheel. The turn of the card. The time of your life. Date of your birth. Year of your death. In the Book of Numbers, the Lord said, Thou shalt count thy steps.

Jack Manfred in Croupier (1998)

I FIRST BUMPED into Mike Hodges in January 1998, at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, for the launch of an earlier book of mine, Alex Cox: Film Anarchist. At the time, although I didnt realize it, he was in the middle of putting together Croupier. A few months after our initial meeting, I saw Croupier at a preview screening in London.

In the warm, dark recess of that movie auditorium in Soho I watched struggling writer Jack Manfred (Clive Owen) take a job as a croupier to make ends meet, and then dispassionately observe the losers at his table. Eighty-seven minutes later, life was a different prospect altogether. Hodges, with a highly intelligent script by Paul Mayersberg, had highlighted my own personal chaos. As the credits rolled, I picked up my diary, my filofax and my mobile phone. But by this point, I could at least hear my own personal wheel spinning.

Croupier, I thought, was a fantastic piece of filmmaking and I knew I had to meet with Mike again. Thanks to an introduction from Alex Cox, we met at a crowded pub in North London, and it was there that he agreed to help with this biography.

Hodges career has been marked with enormous critical and varying commercial success. Features as disparate as Get Carter (1971), Flash Gordon (1980), Black Rainbow (1989) and Croupier (1998) are some of the seminal films in their respective genres.

In fact, Hodges versatility seems nearly endless. Get Carter (1971), was his debut feature film. A seminal thriller that redefined the gangster genre for British moviemakers, it firmly established him as a master filmmaker. But even after this initial mainstream success, Hodges wasnt interested in submitting to the kinds of formulas that might ensure great box office. Consider, for instance, his next two films: Pulp (1972), an off-beat satirical comedy, quietly subversive in its approach; and The Terminal Man (1974), a dark and disturbing science-fiction picture, highly effective in driving home a serious warning to society. Admittedly, Hodges was attracted to one mega-budget project, signing up to direct the dazzling, special-effects-filled Flash Gordon (1980) for Dino de Laurentiis, arguably the most successful screen adaptation of a fantasy comic strip, which achieved an international gross of over $100 million.

Squaring the Circle (1984), his innovative television film about an imaginary confrontation between the Solidarity movement, the Church and the Communist party received the International Emmy as the years best production. And in Black Rainbow (1989), Hodges riveted audiences with a multi-layered supernatural thriller that gave Rosanna Arquette the best role of her career as a medium who begins predicting the truth.

Next page