Contents

Guide

CARLO DESTE

A Holt PaperbackHenry Holt and Company, New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For

SHIRLEY ANN

with love

For

M. S. BUZ WYETH, JR.

one of the great editors of our time

In memory of my friend

DAVID S. TERRY,

World War II citizen-soldier, esteemed educator, talented musician, and one who made this world a better place

and

In memory of the victims of the

outrage of September 11, 2001

Prologue:

An Astonishing Man

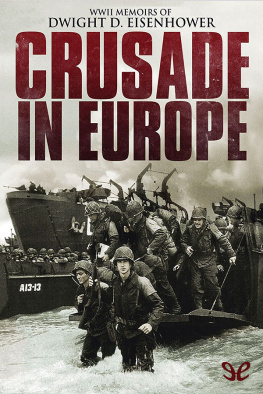

Dwight D. Eisenhower endured many dramatic, tension-filled days, but nothing ever exceeded the events leading up to his courageous decision to launch the greatest military invasion in the history of warfare on June 6, 1944. The outcome of the war hinged on its success. Failure was unthinkable but nevertheless entirely possible, as Eisenhower knew only too well.

More than 150,000 Allied troops, nearly six thousand ships of every description, and masses of military hardware were crammed on ships and landing craft, and on airfields, awaiting Eisenhowers Go order to commence what he would later term the great crusade, the cross-Channel operation that was the necessary overture to victory in Europe.

At the last minute the forces of nature intervened when a full-blown gale swept in from the Atlantic Ocean, and on June 4 Eisenhower was forced to postpone D-Day, originally scheduled for June 5, for at least twenty-four hours while the weathermen consulted their charts and received new data before the next weather update. At 4:15 A . M . on the morning of June 5, 1944, the Allied commanders in chief met to learn if the invasion could take place or would have to be postponed indefinitely. When the meteorologists predicted a break in the weather just sufficient to mount the invasion, Eisenhower made a historic decision that set into motion the most vital Allied operation of World War IIthe operation that would decide the victor and the vanquished. To go or not to go based on this small window of acceptable weather became the basis for a decision only Eisenhower himself could make. And make it he did, deciding that the invasion must be launched on June 6.

In public Eisenhower exuded confidence; in private, however, he was a seething bundle of nervous energy. Ike could not have been more anxiety ridden, noted his British chauffeur and confidante, Kay Summersby. His smoking had increased to four packs a day, and he was rarely seen without a cigarette in his hand. There were smoldering cigarettes in every ashtray. He would light one, put it down, forget it, and light another. On this day, June 5, he drank one pot of coffee after another and was once heard to mutter, I hope to God I know what Im doing. Time dragged interminably, each hour seeming as long as a day.

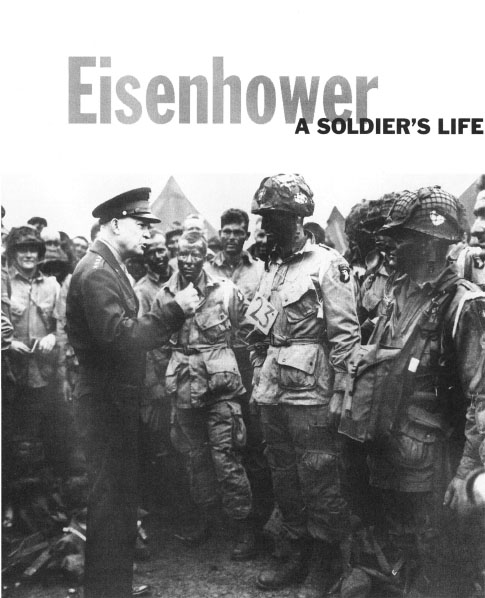

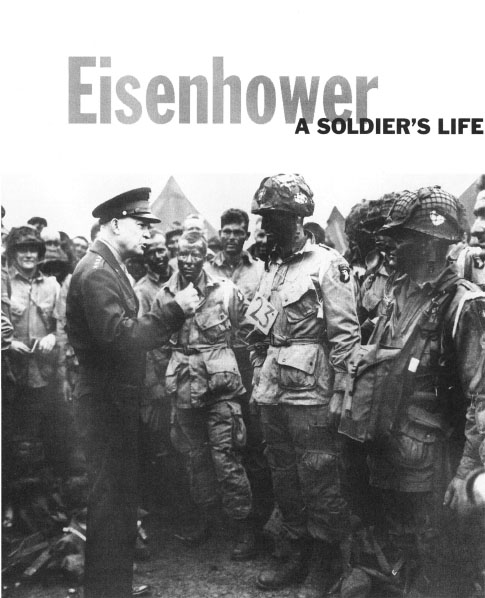

Early that evening, with only his British aide, Lt. Col. Jimmy Gault, for company, he had Kay Summersby drive him to Newbury, Wiltshire, where the U.S. 101st Airborne Division was staging for its parachute and glider landings in Normandys Cotentin Peninsula that night to help protect the landings on Utah Beach. Beginning that afternoon, the division had marched to its loading sites to the strains of A Hell of a Way to Diealso known as He Aint Gonna Jump No More, the song was actually The Battle Hymn of the Republic with lyrics appropriate to paratroopersplayed by the division band. Arriving unannounced, he ordered the four-star plate on the front of his automobile covered, and permitted only a single division officer to accompany him on a random stroll through the ranks of the paratroopers, their faces blackened, full combat packs weighing an average of 125 to 150 pounds littering the ground around them, as they awaited darkness and the signal to begin the laborious process of loading. Although Eisenhower never spoke or wrote much about the experience, he cannot have forgotten the ominous warnings of his air commander in chief, Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, that he fully expected casualties among the men of the elite airborne to be prohibitively high.

In total informality Eisenhower wandered from group to group, as men crowded around him, anxious to meet the general known as Ike. As he moved among the ranks he would ask repeatedly, Where are you from, soldier? What did you do in civilian life? Back came replies from young men from virtually every state in the Union. Some joked with Eisenhower, others remained somber. One invited him to Texas to herd cattle at his ranch after the war. They went crazy, yelling and cheering because Ike had come to see them off.

Possibly the most famous photograph of Eisenhower taken during the war depicts him surrounded by Screaming Eagles (the 101sts nickname), as he questioned one of the jumpmasters, Lt. Wallace Strobel, who assured him that he and his men were ready to do the job they had been trained for. Strobel would later say of his brief encounter with the supreme Allied commander, I honestly think it was his morale that was improved by being with us. Others interjected remarks such as, Dont worry, General, well take care of this thing for you. As twilight settled over southern England, the men of the 101st began the tedious process of loading aboard their C-47s and gliders. Eisenhower went to the runway to see them off, wishing them good luck. Some saluted and had their salute returned. One paratrooper was heard to announce, Look out, Hitler. Here we come!

In some respects the scene was surreal: brave young men, many of whom would be wounded and perish in the coming hours and days, camouflaging their natural fears with bravado; and their commander in chief, deeply cognizant of what he had wrought, concealing his apprehension with smiles and small talk. Its very hard to look a soldier in the eye when you fear that you are sending him to his death, Eisenhower later related to Kay Summersby. Yet those who had seen or spoken with him that fateful night carried into battle a conviction that their top soldier cared personally about each of them.

By nightfall Eisenhower had visited three airfields, at each of which the cheering was repeated. I found the men in fine fettle, he said, many of them joshingly admonishing me that I had no cause for worry, since the 101st was on the job and everything would be taken care of in fine shape. The last man to embark was the division commander, Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, who would shortly parachute into a Normandy cow pasture. Eisenhower saluted Taylors aircraft as it moved off to join the enormous queue awaiting takeoff.

The noise was deafening. Eisenhower and the members of his party climbed onto the roof of the division headquarters to watch in silence as hundreds of planes and gliders lumbered into the rapidly darkening sky, again saluting as each aircraft passed by. For Eisenhower, a man unused to expressing his emotions publicly, it was a painfully moving yet exhilarating experience, and the closest he would come to being one of them. NBC correspondent Merrill Mueller stood nearby and noted that Eisenhower, his hands deep in his pockets, had tears in his eyes.