Contents

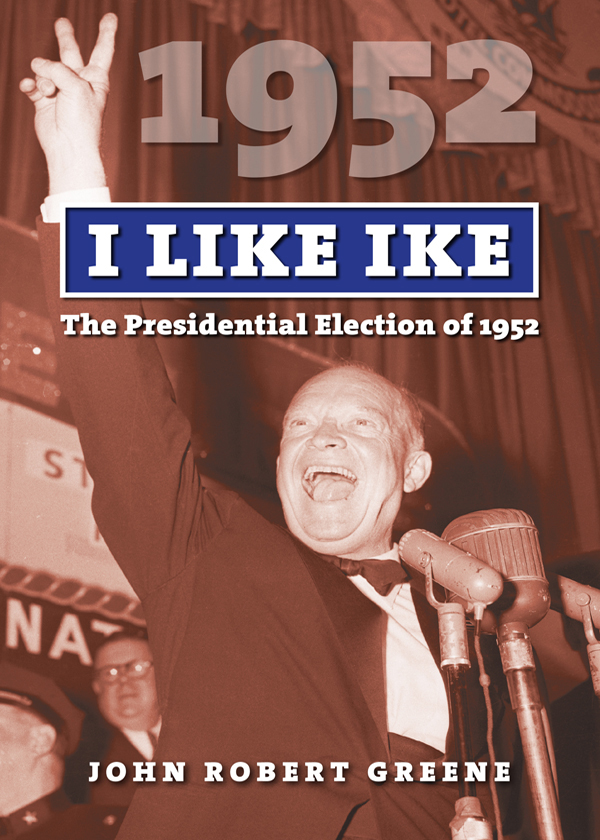

i like ike

American Presidential Elections

MICHAEL NELSON

JOHN M. MCCARDELL, JR.

i like ike

THE PRESIDENTIAL

ELECTION OF 1952

john robert greene

2017 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Greene, John Robert, 1955 author.

Title: I like Ike : the presidential election of 1952 / John Robert Greene.

Description: Lawrence, Kansas : University Press of Kansas, 2017. | Series: American presidential elections | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016047603 | ISBN 9780700624041 (hardback) | ISBN 9780700624058 (paperback) | ISBN 9780700624065 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: PresidentsUnited StatesElection1952. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Presidents & Heads of State. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Process / Elections.

Classification: LCC JK526 1952 .G74 2017 | DDC 324.973/0918dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016047603.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

For Patty, T. J., Kate, Chris, Jenny, Mary Rose, and Luna

CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been writing books now for thirty-five years, and from that experience and the writing of this book in particular, I have learned a very valuable lessonone that leads me to make a modest proposal to the publishing industry. I have come to believe that it should be required of authors of every nonfiction book that they agree to revisit that same topic twenty years later and write another book on the same topic. I float this proposal with tongue only mildly in cheek; the book that follows sprang from just such a revisitation, and it was a career-changing experience.

In 1985, I published my first book, The Crusade: The Presidential Election of 1952. It was a(n ever so slightly) revised dissertation, which meant two things. First, while it was the best I could do at the time, the writing wasnt great. And two, I was trying to break into the business by defending a revisionist thesis that would make me stand out from the academic crowd. My archival research was strongI vaguely remember driving all over the country in a well-dented Ford Pinto and consulting every document I could find. I looked at the documents with the eye of a youthful skeptic. I argued that in 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai E. Stevenson II, both of whom repeatedly told their supporters and the world that they did not want to be candidates or to campaign for the presidency of the United States, were little more than Machiavellian dissemblers. Indeed, I came within a hairbreadth of calling both of them liars. Instead, I settled for a new term (dissertations and first books are full of new, catchy terms)Non-Participant Politicsarguing that while they consistently said that they didnt want to run, in reality they did want to run. But saying that they didnt want to run was part of a calculated strategy designed to make both men more appealing to a public that was sick of politics as usual, particularly during the Korean War phase of the Truman administration. I liked what I wrote, and I was proud of the output. I moved on to other things.

For whatever reason, I have remained the only writer to have produced a book-length monograph on the whole of the presidential election of 1952. Thus, while I was toiling in different historical vineyards, I continued to be called upon to speak on the subject, which I gladly did, without revising the conclusions I had come to in 1985. My Non-Participant Politics argument was great fodder for audiences that loved either Eisenhower or Stevenson, and during the question-and-answer session they would often come at me with a vengeance, charging that I had characterized their hero as a liar. My thesis was like red meat thrown at angry lions, and the resulting give-and-take was always fun.

That is, until I was asked by Daniel Holt, then the director of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas, to deliver the keynote address at a daylong conference, titled The Great Crusade: The Road to the White House, 1952, held in November 1992 on the fortieth anniversary of Eisenhowers victory. My job was to set the table, so to speak, for the alumni of the era who had joined the panelincluding Abbott and Wanda Washburn of the Citizens for Eisenhower, former governor of Minnesota Harold Stassen, NBC News correspondent Ray Scherer, and Herbert Brownell, Eisenhowers political Yoda in 1952 and ultimately his attorney general. When I spoke, I laid it on thick about Eisenhower and Stevenson and their political deceit. Polite applause followed my talk, and then we adjourned. As I moved away from the podium, I saw the panelists huddling. I started to walk toward them, but Scherer intercepted me. With a wide grin, he quietly mumbled, Dr. Greene, you dont want to go over there. I froze and took my seat at the table onstage. Sitting next to me was Brownell, who, as was his wont, immediately began to make small talk with me while we reset for the next session. But I could not help myself. General Brownell, I quietly pleaded, what were you folks discussing over there? He smiled but did not look me in the eye as he slowly intoned, Oh, we liked your speech. But you know, dont you, that you are dead wrong? Believe me when I tell you that no negative book review can hit you quite as hard as that. They were gentlemen all; none of themnot Brownell, not Abbott Washburn (who quietly took me to task on another break)said anything remotely critical about my work in public during the conference, and they continued to be polite with my lame attempts to wheedle into their conversation with the audience about the campaign (I mean, for a bit, I was shaking). But my notes for that days conference belie a bit of an epiphany; on the back of a program, in big block letters, I scribbled: Was I wrong?

That question would dog me for the next two decades. Although given the opportunity to speak on the election on several more occasions, I found myself backing off from the stridency of my thesis. I used words that had not been in my younger lexiconwords like might and perhaps. I began to consider revisiting the election, but the opportunity to rethink The Crusade was buried in a host of other projects and responsibilities: that is, until 2013, when I first spoke with Fred Woodward, then the director of the University Press of Kansas and now the emeritus director of that press, about writing a book on 1952a new bookfor its American Presidential Elections series. Fred always reminded me of what I like to think the editors of the great trade houses in New York City were like: nurturing their authors ideas, tolerating their peculiarities, and, in general, being shepherds who help the author move a good book from his or her mind to the printed page. Thus, he didnt shoot me down when I said that I wanted to fix (I think I used that wordif I didnt, I should have) The Crusade. After finishing a few books that I had been working on, including one for Kansas, where, for the first time, I revised and expanded a previous work, I was ready to begin on 1952.