Copyright 2017 by Stephen Paul DeVillo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

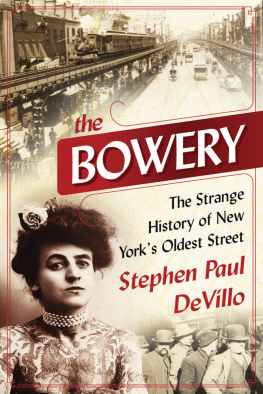

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover photo credits: Library of Congress

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2686-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2687-1

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Preface

The Bowery isnt what it used to be. And in fact, it never was. New York Citys oldest thoroughfare, the Bowery has both reflected and shaped the ever-changing city it helped give birth to. Throughout its long, lively, and sometimes tragic history, the Bowery has hosted an endless parade of farmers, drovers, soldiers, coppers, gangsters, statesmen, showmen, magicians, poets, writers, artists, and unfortunates. Fur traders gave way to farmers, whose farms in turn gave way to taverns, tanneries, saloons, circuses, dime museums, tattoo parlors, speakeasies, flophouses, brothels, and religious missions. The Bowerys cavalcade continues today as this long-avoided boulevard experiences a dramatic rebirth. Well-dressed visitors now head to the Bowery, not as a place to go slumming, but as a world-class destination for contemporary art and music.

Its been an astonishing four-hundred-year-long story that I would like to share with you. A lifelong New Yorker, Ive long been fascinated with the citys lesser-known nooks and byways, the small places that often contain a larger history. Venturing down the Bowery just as it was reemerging into the daylight in the 1990s, I wondered what tales its old buildings could tell me, and found there are many such tales to tell. Come with me as we take a walk through time as we stroll down the once infamous Bowery.

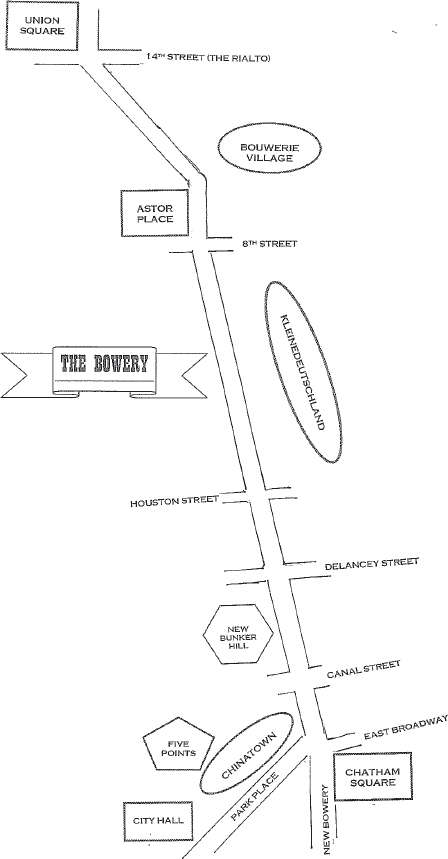

1 The Great Bouwerie

LIKE MANY LATER VISITORS TO New York, the first European settlers made their way to the Bowery. Coming from the Netherlands, they sought not thrills, but furs and farms. It wasnt yet called the Bowery back then, but it was already an old thoroughfare. From the Harlem River crossing at the far northern end of the island, a Native American trail ran down the east side of Manhattan to an area just south of a large pond. From there a short trail led to a village on Werpoe Hill on the west side of the pond. Another trail branched east to the small village of Nechtanc where Corlears Hook jutted into the bend of the East River, while the main trail continued on to the canoe landing at the far southern tip of the island, where Castle Clinton stands today.

Running the length of the island, the trail connected different groups of the Lenni Lenape, or Delaware nation. The Canarsee (or Werpoes) occupied the southern part of the island, while the Rechgawawank occupied the north end, and the trail that was to become the Bowery served then, as it would later, as a connection and meeting ground among different groups. Apart from linking the bands living on the island, the trail served trading parties from the mainland to the north and east, and a branch led to Sapokanikan on the islands western shore, where Indians from west of the river would paddle over to trade deer and elk meat for tobacco at a place that would become the Meatpacking District.

The Bowerys reputation as a place of sharp dealings may well have begun with Peter Minuits legendary twenty-four-dollar land deal. Minuit, the director of the New Netherland colony, is credited with swapping sixty Dutch guilders worth of European goods for the whole of Manhattan island. However, the precise location and circumstances of this transaction are uncertain. Whether it happened at Shorakapkok near present-day Spuyten Duyvil, or if, as was more likely, it took place at Werpoe Hill by the Collect Pond, the fact was that no single group possessed the entire island. The Canarsee people at Werpoe Hill had rights only to the southern end of the island; the rest was occupied by other Lenape groups, not least of which were the Rechgawawank on the northern end, who would sell their territory only in pieces. The last of the Rechgawawank wouldnt leave Manhattan until 1715, over ninety years after Peter Minuits legendary purchase of the island.

Like the thousands of commuters who today follow old Indian routes to the island, the Dutch came to Manhattan for business. The southern tip of the island faced one of the finest harbors in North America, from which ships could sail across the Atlantic to markets in Europe or outfit privateers for a bash at the Spanish Main. Manhattan moreover lay alongside the great waterway that the Dutch knew as the North (later Hudson) River, which, like the trail, pointed north toward the sources of beaver furs. Dutch fur traders had been on Manhattan for over ten years before the West India Company planted a permanent settlement there in 1624. New Amsterdam served as a trading post and overseas shipping point for furs sent down from Fort Orange, site of present-day Albany. With the Eurasian beaver long hunted out, American beaver furs were a valuable commodity, prized for making felt for the big wide-brimmed hats that in those days defined gentlemen of fashion.

The Dutch West India Company was sure that New Amsterdam would prove to be a gold mine, but it needed a stable foundation, and that meant settlers who could create an agricultural base to provide a reliable food supply. The Dutch accordingly laid out six farms, or bouweries in Dutch, along the trail north of New Amsterdamfive small farms plus the Great Bouwerie, which will figure in the story later. These six bouweries were named after their owners: Blyevelt, Schout, Wolfert, Van Corlear, Leendert, and Pannepacker.

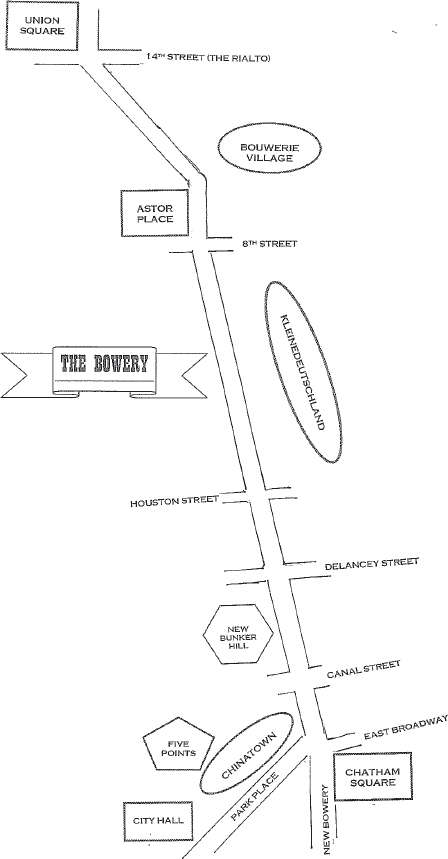

The Indian trail linked the farms together so it became known as the Bouwerie Lane. Almost immediately, however, the process began of chopping the Bowery down from its original thirteen-mile length to its current stretch of only two miles. The Dutch gave the southern end of the trail the grandiose name of Heere Straat (Broadway), which ran up to present-day Ann Street. There the trail became the Heere Wegh (Highway) following the line of todays Park Row, becoming Bouwerie Lane only once it was past todays Chatham Square.

Foreshadowing its history, the trail became the scene of New Yorks first mugging shortly after the establishment of New Amsterdam. A Lenape came down the trail with his young nephew, bearing a load of furs for trade to the Dutch. As the pair approached the pond, they were jumped by three men who murdered the Lenape and made off with the furs. Not wanting to deal further with the Europeans, the boy didnt try to report the murder but simply made his way back home, determined to someday settle accounts.