HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

FIRST EDITION

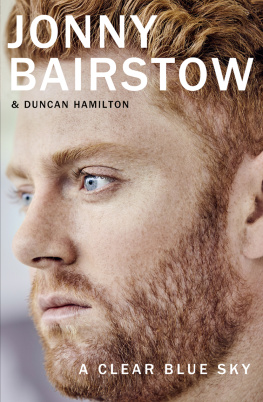

Jonny Bairstow 2017

Cover design by Clare Ward HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover photograph Adidas

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Jonny Bairstow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008232672

Ebook Edition October 2017 ISBN: 9780008232702

Version: 2017-09-14

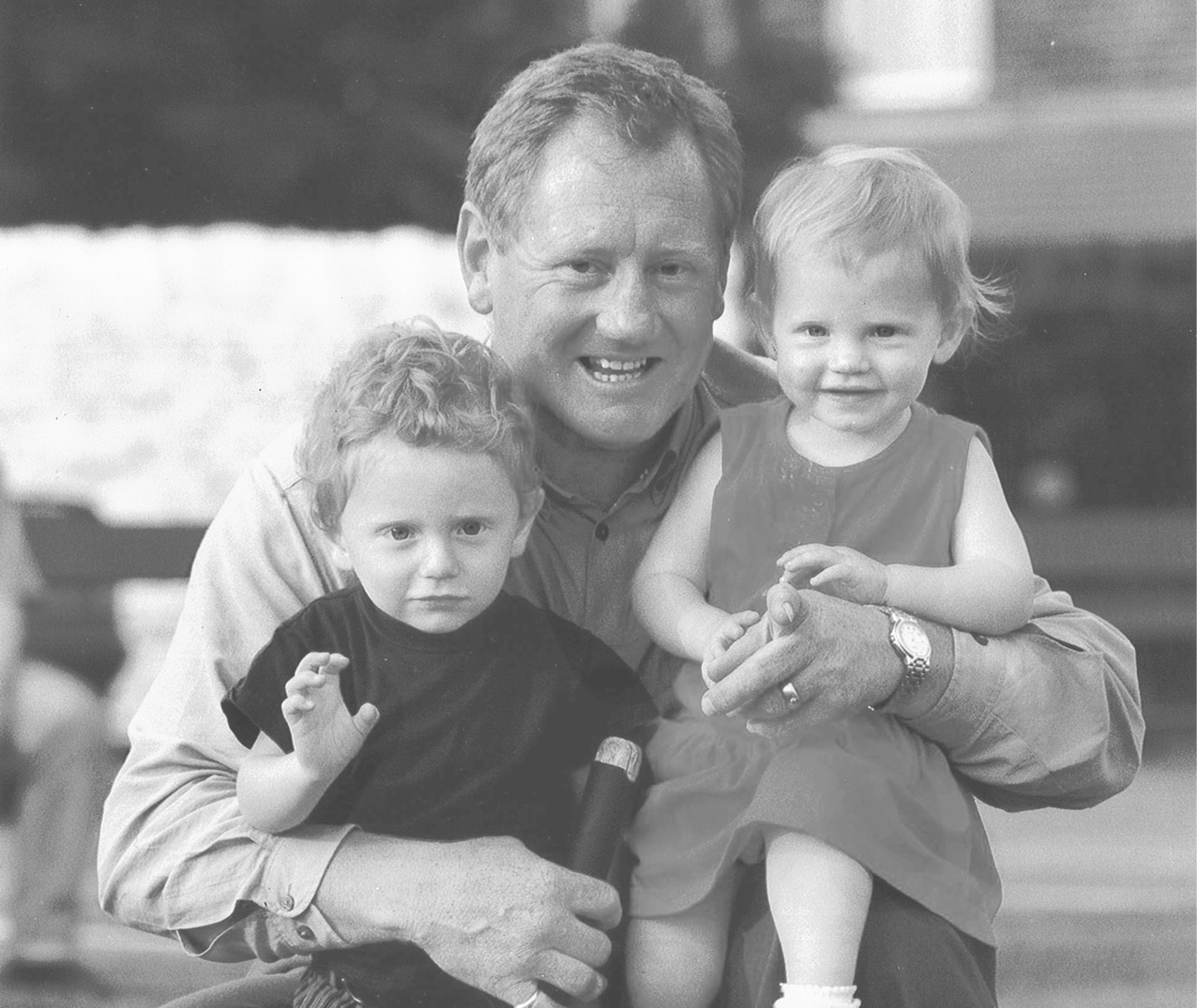

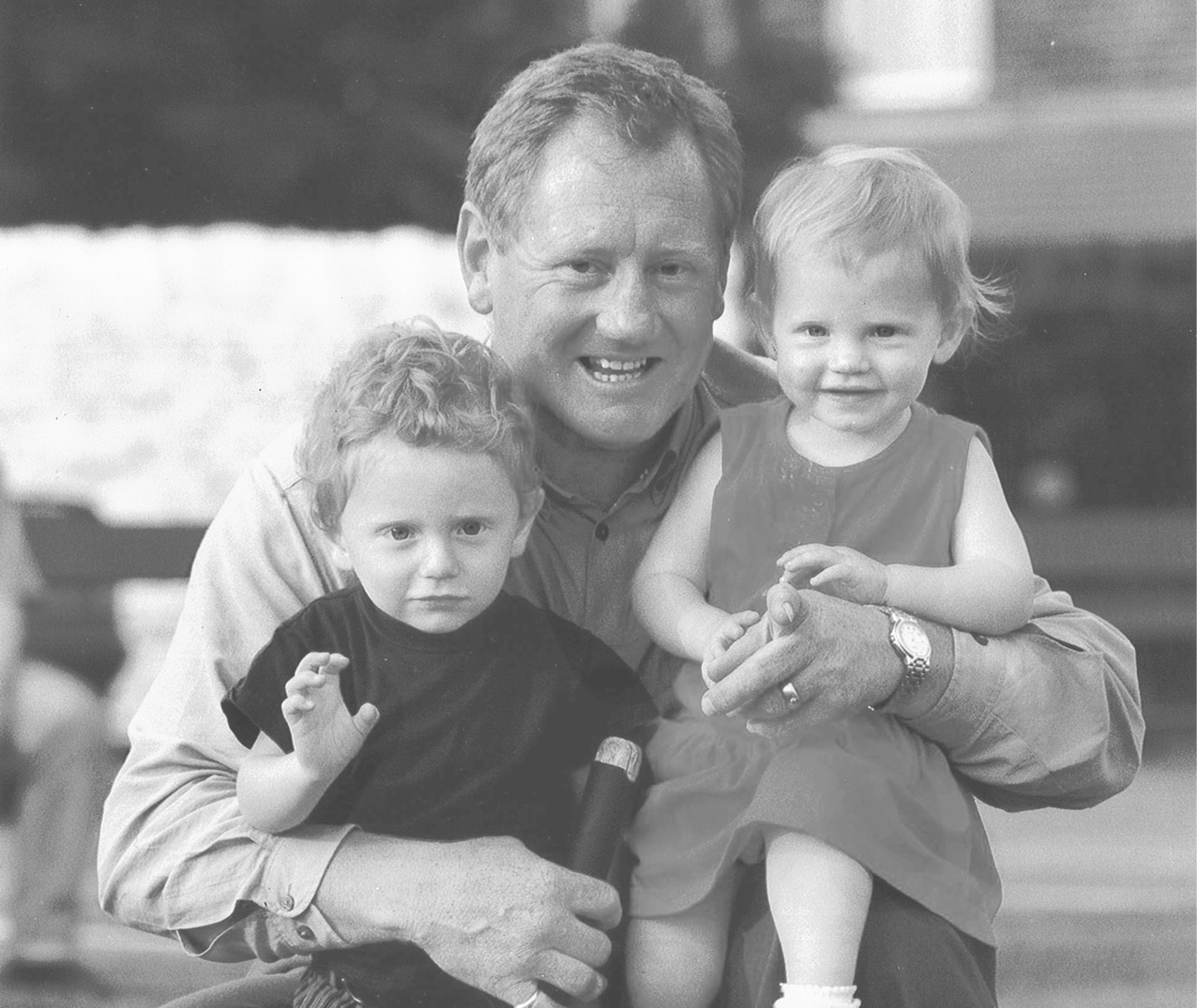

To Mum, Dad and Boo

( Authors collection)

( Authors collection)

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Cape Town, 3 January 2016

Ive been batting for more than three and a half hours. Ive faced 160 balls. Im on 99 a nudge, a nick, a heartbeat away from my first Test century.

Just one more run

This South African afternoon is heavy with a dry heat. The sky, shining without clouds, is as bright as the blue in a childs paint box, and the glare makes everything around me seem profoundly sharper: the sweep of a full, noisy ground, the purple-grey outline of Table Mountain and the jaggedness of Devils Peak, and even the vivid emerald of the outfield. In my head Im talking all the time. Im reminding myself, as I always do, of the simple things that are so damned difficult to get right. Stay focused. Appear calm, almost nonchalant. Dont let the bowlers get on top. And dont, on any account, show a sign of apprehension.

Between deliveries Ive occasionally drifted out of my crease and patted down or brushed away some imaginary speck of dirt simply because I wanted something to do, something to keep me busy and alert. Or Ive occupied myself in other ways: twirling my bat in my hand, tugging at my shirt and readjusting my helmet. These small tics are displacement, each designed to banish the sort of thoughts that can gremlin the mind. When youre so close to a hundred, its easy to lose concentration. Your mind can go slack, wandering off abstractedly. Then the hard, sweaty graft thats gone before is undone in a nanosecond. So I have to stay in the moment. I mustnt get ahead of myself. I cant afford to think about the relief Ill feel when this is over and gone, already part of my statistical record. I cant afford to think about how handsome my name, illuminated on the scoreboard in big capital letters, will look with three figures beside it. And I cant afford to think about what the century will mean, professionally as well as personally. Most of all, I mustnt dwell on how I will feel or how I will celebrate in the middle. Or how my mum Janet and my sister Becky, who are sitting near the pavilion, will feel and celebrate too. Or how proud I will make them this week of all weeks.

In two days time it will be the familys black anniversary: the date of my dads death in 1998. How quickly that always seems to come around. We mark it only among ourselves, and we do so very quietly, remembering the best of him rather than the tragedy of that day. New Year creeps up like a forewarning, and we get ourselves ready for the anniversary in our different ways. They say that for sorrow there is no remedy except time. Every turn of the calendar puts more distance between us and the raw pain of the event, but even a couple of decades on it scarcely lessens the degree of it. A stab of that pain always comes back.

When my dad died, taking his own life, I was eight years old. Becky, who everyone knows as Boo, was seven. My mum had cancer, the first of two bouts of the disease that shes fought and beaten. In that dark time the worst imaginable the three of us held tight to one another like survivors of a shipwreck. It was our only way to get through it. Our house, like our lives, seemed bare and empty and quiet, and our grief seemed inconsolable. We were hollowed out. But we had each other then and we have each other still and slowly we learnt to live without him. We came to accept his death, even though we dont understand it now any more than we did then.

Everyone believes their family is special. Mine just is. It isnt only about love. Its also about understanding and trust, support and the empathy between us. Because of what happened, and the way in which we coped with it, the three of us are as close as its possible to be, our bond unbreakable.

I got a lot more genetically from my dad than my red hair. I got his eye for a ball. Early on I think he realised it or at least suspected that I could be a prodigy of sorts. Were he alive, or if he could come back to us for just one day and how many occasions have I thought about that scenario? I dont think hed be too surprised to discover that Im playing for Yorkshire and England. I bet hed just give a nod and a knowing smile and say he expected nothing less from me.

When I was the smallest of small boys, a mere lick of a thing, I liked to play pool. My dad and I were once in a pub in North Yorkshire, one of those olde worlde places with low black beams and horse brasses. He had his pint. I had my apple juice. I couldnt have been more than six years old, possibly even a little younger. The two of us were at the table when a cycling club came in, wanting to play too. I have an inkling that there were five of them. My dad bet a fiver, I think that I could take on and whip the lot of them single-handed. The cyclists couldnt have been more incredulous if my dad had claimed to own a dog that could sing and dance. I was so short that I had to stand on a stool to make a shot. They looked at him as though hed already drunk several beers too many. They looked at me a wide-eyed, freckled lad and accepted the wager without hesitation, certain of some easy cash. I took each of them to the cleaners, much to their mounting stupefaction and my dads immense satisfaction. I know he wouldnt have made the bet if he hadnt thought I would win it; losing would have embarrassed both of us. So he must have thought his sporting streak was in me too.

If only I could ask him

He taught me how to hold a cricket bat. Pick it up like an axe, hed say. Grip it as though youre about to chop wood. In knockabout games in our back garden, and especially on beaches as far flung as Barbados and Scarborough, hed encourage me to give the ball a good tonk for the sheer joy of it. Id swing my spindle-thin arms at a delivery, trying to belt a huge six to impress him. Id use one of his old bats a V500 Slazenger which hed sawn down to my size. I kept that bat close to me, almost sleeping with it.

Next page